Exploring the Moon

A history of lunar discovery from the first

space probes to recent times

Lunar exploration since Apollo

After the Apollo and Luna series ended, interest in the Moon waned. For the next two decades, attention turned to exploring the rest of the Solar System. The next Moon probe, in 1990, was not American, or Russian, but Japanese. Called Hiten, it was only a test of spacecraft technology and returned no real scientific results, but it was an indicator of Japan’s growing ambitions in space.

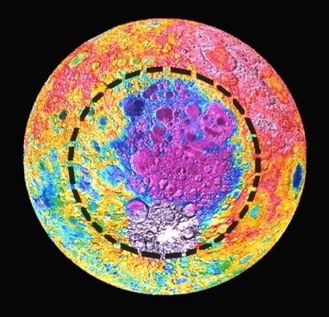

The United States resumed its lunar exploration in 1994 with a probe called Clementine, a joint project of the Department of Defense and NASA. Its real purpose was to test military sensors, which it did in a scientifically productive way by using them to study the Moon. From an orbit passing over the Moon’s poles, Clementine scanned the entire Moon at a wide range of wavelengths from the ultraviolet to the infrared, allowing scientists to map the distribution of elements such as iron and titanium which reveal the differing compositions of the bright highlands and dark lowlands. Clementine also measured heights with a laser altimeter, building up a topographic map that showed for the first time the full size and depth of the South Pole–Aitken Basin (pictured above), the largest impact structure in the Solar System.

A follow-on mission, Lunar Prospector, was designed to find out more about the Moon’s crust and interior, which would improve our understanding of its origin and geological history. At first, it was thought that one of Lunar Prospector’s instruments, the neutron spectrometer, had detected signs of ice on or near the surface in the permanently shaded regions near the Moon’s poles, presumably deposited by impacts from comets over the millennia. To test this possibility, when Lunar Prospector had completed its mission it was deliberately crashed into a crater near the Moon’s south pole at the end of July 1999, and astronomers on Earth looked for the resulting splash. Unfortunately they did not detect any signs of water vapour thrown up by the impact. The quest for icy deposits at the lunar poles has been continued by more recent probes.

Europe joined the Moon club in September 2003 when the European Space Agency launched a probe called SMART-1 (the name stands for Small Missions for Advanced Research in Technology). It was a testbed for various technologies being developed for future planetary missions. Using an experimental solar-electric propulsion system SMART-1 took 14 months to reach the Moon, eventually entering an orbit passing over the poles from where it took detailed photographs and continued studies of the mineralogy of the Moon. When its mission was over, it was deliberately crashed into the surface about 100 km southwest of the crater Lee in the Moon’s southern hemisphere, producing a flash that was seen through telescopes on Earth.

South Pole–Aitken Basin, the biggest dent

in the Moon

Lunar exploration since Apollo

Probe

Launch date

Results and notes

1990 January 24

Japanese Space Agency technology development mission

1994 January 25

Mapping of lunar surface composition and topography

1998 January 7

Continued surface composition studies and mapped the Moon’s gravitational field

2003 September 27

Topography and mineralogy studies