Antinous (pronounced ‘anti-no-us’) was the boy lover of the Roman Emperor Hadrian and hence is a real character, not a mythological one, although the story reads like fiction. Antinous was born c. AD 110 in the town of Bythinium (also called Claudiopolis), near present-day Bolu in north-western Turkey. At that time this area was a Roman province, and Hadrian is thought to have met Antinous during an official visit. Hadrian, the first openly gay Roman Emperor, was smitten by the boy and groomed him to become his constant companion.

Hadrian’s happiness did not last long, though. While on a trip up the Nile in AD 130, Antinous drowned near the present-day town of Mallawi in Egypt. Supposedly an oracle had predicted that the Emperor would be saved from danger by the sacrifice of the object he most loved, and Antinous realized that this description applied to him.

Whether the drowning was accident, suicide, or even ritual sacrifice, Hadrian was heartbroken by it. He founded a city called Antinoöpolis near the site of the drowning, declared Antinous a god, and commemorated him in the sky from stars south of Aquila, the Eagle, that had not previously been considered part of any constellation.

Antinous was mentioned as a sub-division of Aquila in Ptolemy’s Almagest, although it is not included among the canonical 48 Greek figures. Ptolemy worked at Alexandria at the mouth of the Nile and he compiled the Almagest about 20 years after the famous drowning so he would have known the story; indeed, he might have had a hand in creating the constellation, possibly at Hadrian’s request.

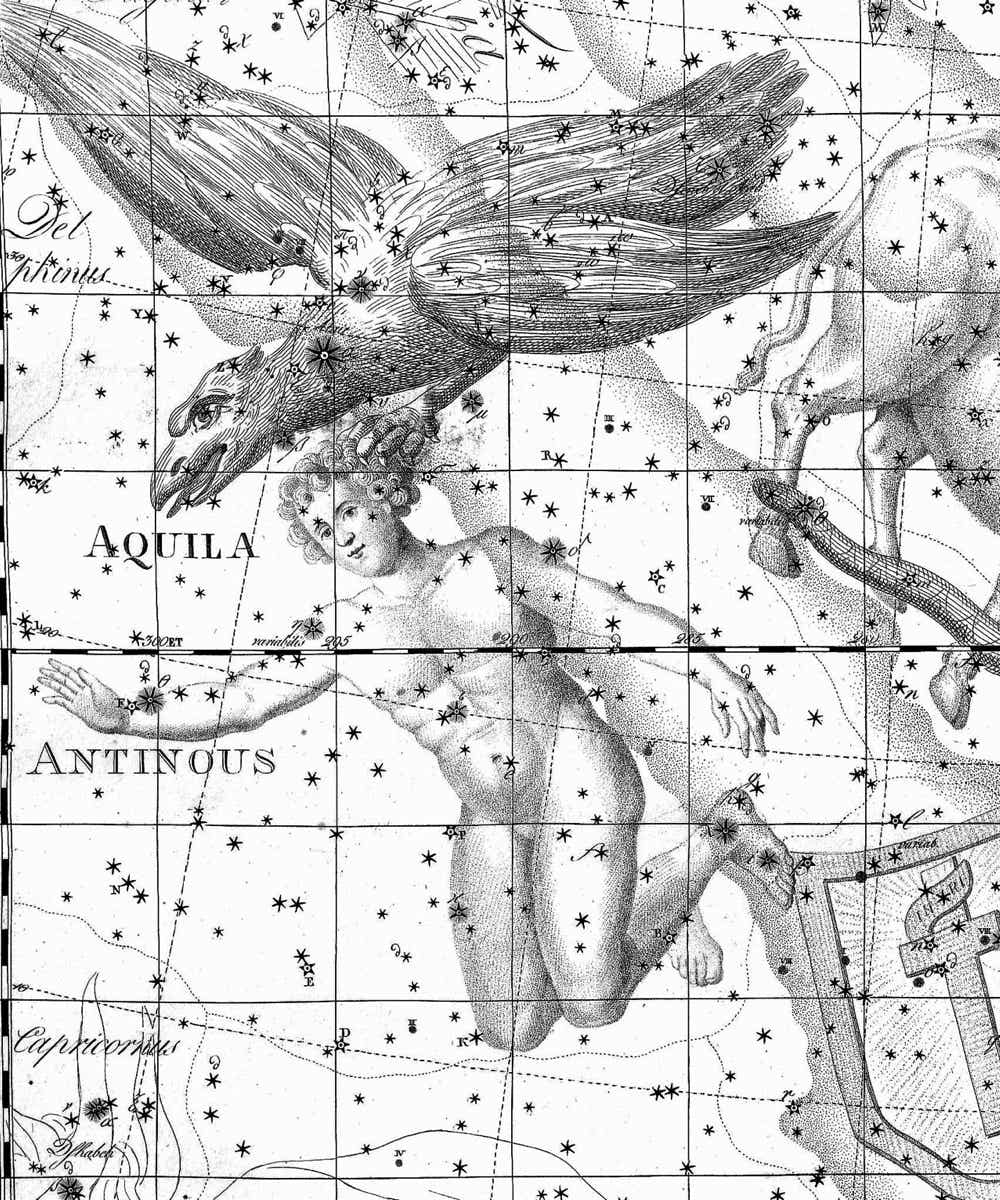

Antinous carried in the claws of Aquila the Eagle, seen on Chart IX of the Uranographia of Johann Bode (1801). Here, the eagle is shown in a rather awkward perspective, from above. However, Ptolemy’s description in the Almagest makes it clear that the eagle should be imagined as though seen from below, which is how the classically correct John Flamsteed showed it on his Atlas Coelestis of 1729, although without the burden of Antinous. On Bode’s chart the star in the right shoulder of Antinous is labelled ‘variabilis’; this is Eta Aquilae, one of the brightest Cepheid variables known.

According to Ptolemy, Antinous consisted of six stars of 3rd to 5th magnitude, which we now know as Eta, Theta (the brightest at magnitude 3.2), Delta, Iota, Kappa, and Lambda Aquilae. These six stars can be seen, for example, on Albrecht Dürer’s star chart of 1515, although Dürer did not show the figure of Antinous himself. The constellation’s first known depiction was in 1536 on a celestial globe by the German mathematician and cartographer Caspar Vopel (1511–61); it was shown again in 1551 on a globe by Gerardus Mercator. Tycho Brahe listed it as a separate constellation in his star catalogue of 1602 (albeit with only three stars) which ensured its inclusion on many subsequent charts.

Johann Bayer imagined Antinous grasped in the claws of Aquila, as did Bode (above). On other charts, though, Antinous seems to be free-flying, as befits a young god. Hevelius equipped him with a bow and arrow, perhaps symbolizing his participation in Hadrian’s hunt of the man-eating Marousian Lion in Libya. Because of his position beneath Aquila, Antinous has sometimes been confused with Ganymede, another celestial catamite, who was carried off by an eagle for Zeus, but he is actually represented by Aquarius.

Antinous remained widely accepted into the 19th century, when its stars were eventually remerged with Aquila. Its memory lives on, though, for its brightest star, Theta Aquilae, is now officially named Antinous.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

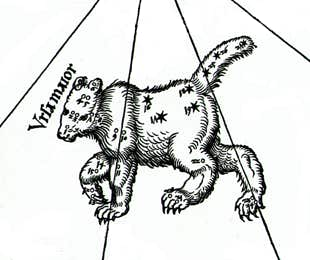

The six stars that Ptolemy described as ‘around Aquila, to which the name Antinous is given’, as seen on Albrecht Dürer’s northern celestial hemisphere chart of 1515. Dürer numbered them 1 to 6, in the order in which they appeared in the Almagest. We now know them as Eta, Theta, Delta, Iota, Kappa, and Lambda Aquilae. Dürer’s chart showed the sky as it appears on a globe, so the constellations are reversed from the way we see them in the sky.

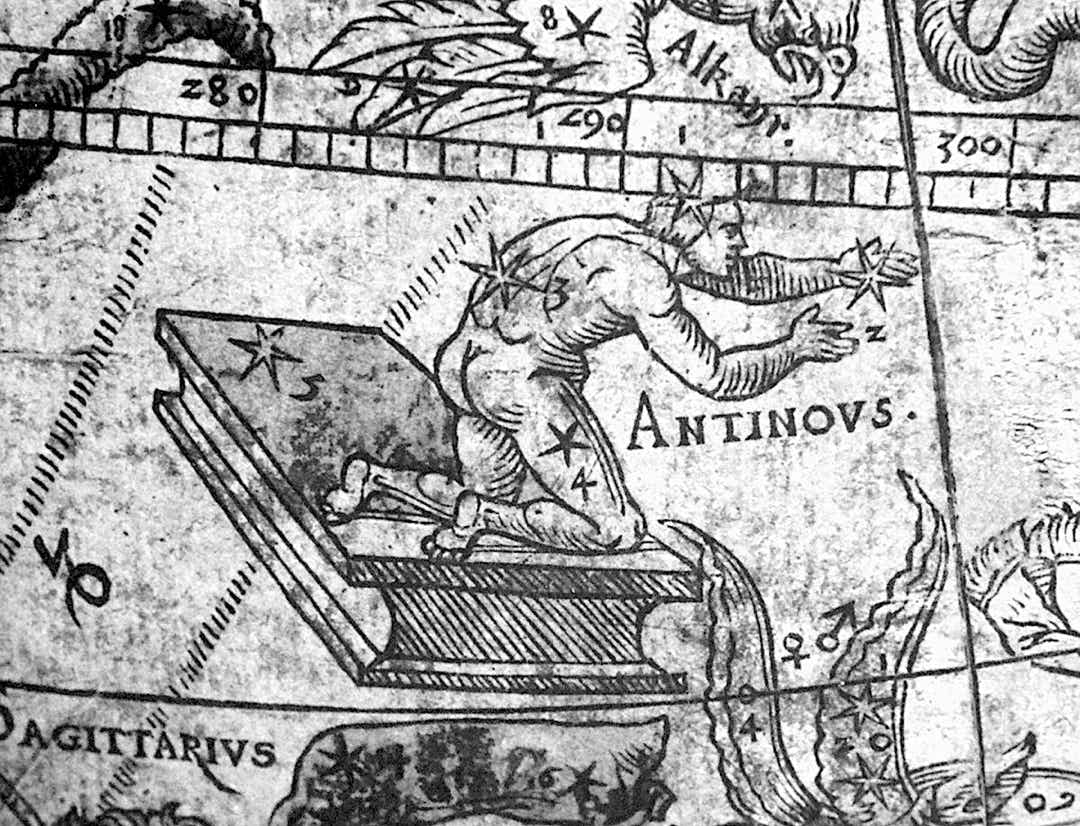

Antinous kneels on a pedestal with arms outstretched and Aquila the eagle hovering above, as depicted on Caspar Vopel’s celestial globe of 1536. The Dutch historian Elly Dekker has interpreted his pose as being ‘at the point of drowning himself’, although he might equally well be imagined as reaching out to his master Hadrian. See Caspar Vopel's Ventures in Sixteenth-Century Celestial Cartography by Elly Dekker. Image courtesy Cologne City Museum.