Charting the Chinese sky

The Dunhuang star chart

This chart, drawn on a long paper scroll, was found in Buddhist caves near Dunhuang on the Silk Road trade route. The caves had been sealed around AD 1000 and were not rediscovered by local people until 1900. Inside the caves were thousands of manuscripts and paintings on paper and silk that had survived almost unaltered in the dry conditions at the edge of the Gobi desert. The explorer Marc Aurel Stein visited Dunhuang in 1907 and obtained many manuscripts, including the star chart, which he sent back to the British Museum. Despite the chart’s significance, it was not fully studied for over a century.

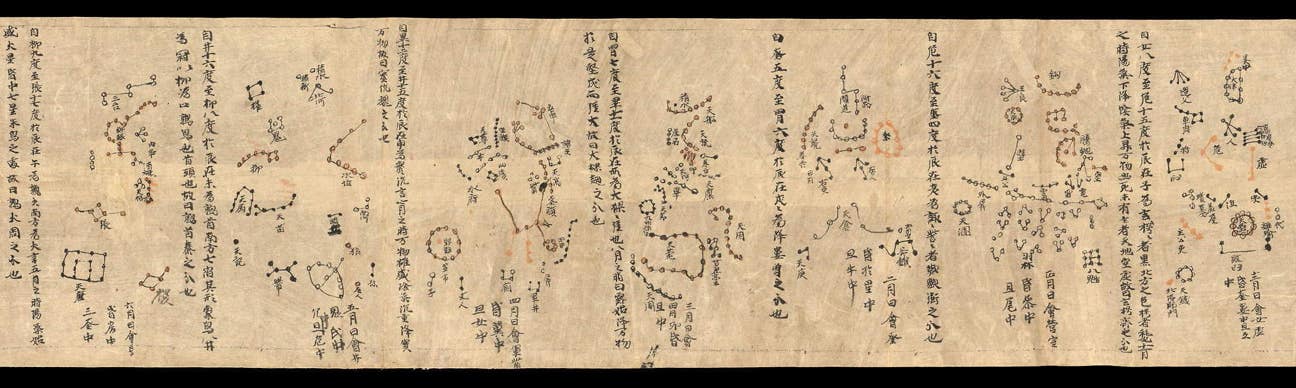

The 13 panes of the Dunhuang star chart form a near-complete atlas of the Chinese sky. It reads from right to left and is divided into two here for convenience of reproduction. Click on the image to see the full scroll. © British Library.

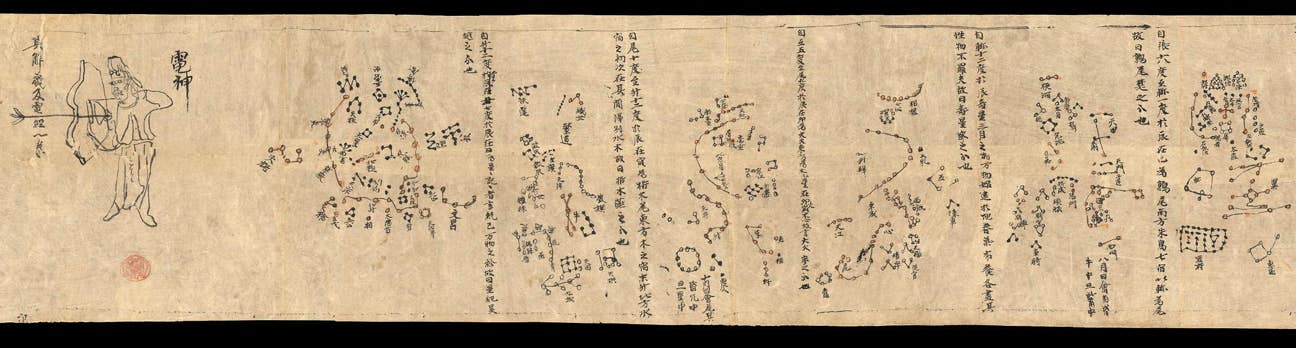

The Dunhuang star chart is drawn in pen and ink on a roll of paper 3.9 metres long and some 24 cm wide. The first third of the scroll is taken up with cloud shapes and their supposed meanings, a reminder that the Chinese observed the sky for the purpose of divination rather than pure science. The section of specific astronomical interest, shown above, is 2.1 metres long. It consists of 12 panels corresponding to the 12 months of the year, with vertical lines of descriptive text to the left of each panel, plus a north polar chart. Hence it can be thought of as not simply a chart but a complete atlas consisting of 13 plates. The scroll ends with the depiction of an archer, thought to represent the god of lightning.

Each of the 12 monthly panels is centred on the celestial equator and extends from about 50° north to 50° south. The polar chart is centred on the celestial pole and shows an area from 90° to about 50° north. Despite a lack of coordinate lines, the placing of the stars is good enough for almost all of them to be identified. Most likely, though, this is a copy of an earlier original, and the copy was probably made by tracing since the paper is semi-transparent, like tracing paper.

Three different styles of dot are used to represent the three different schools of constellation study. In general, the black dots correspond to Gan De’s constellations, the open circles to those of Wu Xian and the orange dots to Shi Shen, although the artist has confused the latter two in many cases. The faintest stars on the chart are around magnitude 6.5, close to the naked-eye limit under the very best conditions. As with all far-eastern star charts, there is no attempt to distinguish the brightnesses of the stars with differently sized dots.

In 2009, a detailed study of the Dunhuang star chart was published by two French astronomers, Jean-Marc Bonnet-Bidaud and Françoise Praderie, working with Susan Whitfield of the British Library. You can read it in full here. By their count, the chart contains 1,339 stars divided into 257 constellations, fewer than the number of stars and constellations in Chen Zhuo’s catalogue; why some were left out remains unknown. Various references in the text and the style of the writing pin down the date of the chart to between AD 649 and 684; although the chart is almost certainly a copy, it was made not long after the original, in that same era. The star positions, which had been updated since the time of Chen Zhuo, also point to a date in the mid to late 7th century. Possibly the positions were observed by Li Chunfeng (602–670), a prominent Chinese astronomer of the right era whose name is mentioned in the text accompanying the maps; he may have been the author of the original chart from which the Dunhuang manuscript was evidently copied.

NEXT:

The Suzhou (Soochow) planisphere ►

PREVIOUS:

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved