Genitive: Lyncis

Abbreviation: Lyn

Size ranking: 28th

Origin: The seven constellations of Johannes Hevelius

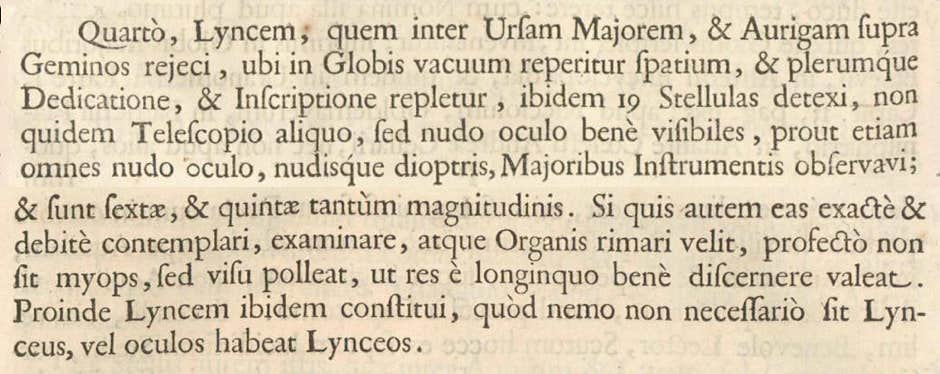

Johannes Hevelius, the Polish astronomer who introduced this constellation in his star catalogue of 1687, continued to measure star positions with the naked eye long after other astronomers had adopted telescopic sights. The French astronomer Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655) wrote in 1644 that Hevelius had the ‘eyes of a lynx’ and this constellation can be seen as an attempt to demonstrate that.[note] Indeed, Hevelius wrote in the Introduction to his catalogue that anyone who wanted to observe it would need the eyesight of a lynx (‘oculos habeat Lynceos’), although he undoubtedly exaggerated the faintness of the 19 stars he catalogued in it, typically by a full magnitude.

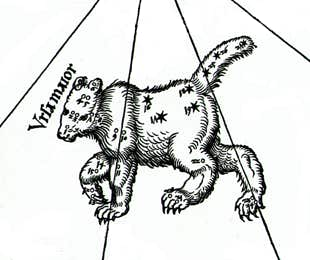

Lynx fills a blank area of sky between Ursa Major and Auriga that is surprisingly large – greater in area than Gemini, for example – but apart from one third-magnitude star (Alpha Lyncis) it contains no stars brighter than fourth magnitude. Six of its stars, all in the rear part of the constellation, had been listed by Ptolemy in his Almagest as lying among what he termed the ‘unformed’ stars outside Ursa Major. These stars can be seen on Albrecht Dürer’s northern celestial hemisphere chart of 1515. Earlier in the 17th century, the Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius had made these stars part of his new constellation Jordanus, the river Jordan, but it was Hevelius’s alternative creation that endured.

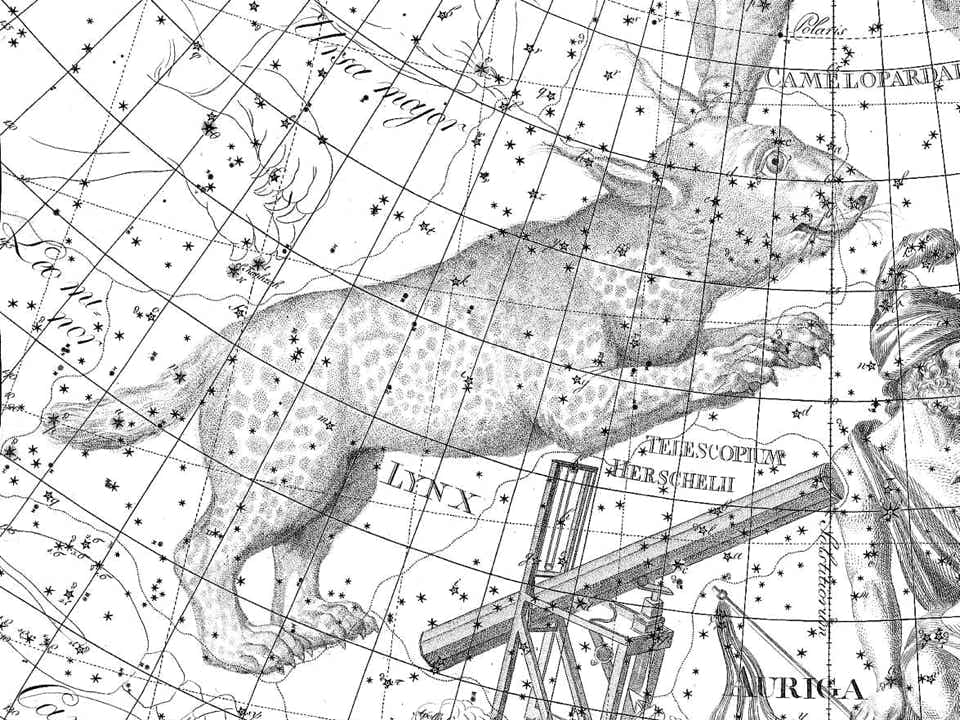

Lynx as shown on Chart V of the Uranographia of Johann Bode (1801).

Click here for Hevelius’s original version of Lynx.

On his star atlas Firmamentum Sobiescianum published posthumously in 1690 Hevelius called the constellation Lynx, while in the accompanying star catalogue it is listed as ‘Lynx, sive Tigris’ (Lynx or Tiger). However, the illustration he presented does not look much like either animal.

It is not known whether Hevelius had in mind the mythological character Lynceus who enjoyed the keenest eyesight in the world – he was even credited with the ability to see things underground. Lynceus and his twin brother Idas sailed with the Argonauts. The pair came to grief when they fell out with those other mythical twins, Castor and Polydeuces (see Gemini).

Alpha Lyncis, magnitude 3.1, is the brightest star in the constellation, and the only one with a Greek letter; the letter was assigned by the English astronomer Francis Baily in his British Association Catalogue of 1845.

Misplaced stars

John Flamsteed, England’s first Astronomer Royal, created confusion in Lynx and its surroundings by cataloguing several stars in this area as part of the wrong constellations. For example, the 44th star in Flamsteed’s table for Lynx actually lies in the chest of Ursa Major, while his 10th and 19th entries for Ursa Major are not in the bear at all but in the tail of Lynx. Similarly, the 50th star he listed in Camelopardalis is well south of that constellation, squarely within the body of Lynx. To prevent confusion, astronomers have dropped official Flamsteed numbers for most of these out-of-bounds stars, although the old numbers are on occasion used for historical reasons. Hence some charts of Lynx incorporate a star labelled 10 UMa.

Chinese associations

Alpha Lyncis, 38 Lyncis, and two other unnumbered stars formed the northern part of the Chinese constellation Xuanyuan, the Yellow Dragon or Yellow Emperor, which extended into Lynx from Leo. But this area of sky is so blank that even the Chinese, despite their fondness for faint constellations, imagined nothing else here.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

This description was contained in a letter written by Gassendi to Hevelius in April 1644; in the letter Gassendi was actually referring to Hevelius’s solar and lunar observations, not his star catalogue.

Hevelius’s description of Lynx from Chapter 8 of his Prodromus Astronomiae, the introductory section to his star catalogue and atlas.

Six ‘unformed’ stars listed by Ptolemy under the body of Ursa Major were incorporated by Johannes Hevelius into his new constellation Lynx. Here they are seen on Albrecht Dürer’s northern celestial hemisphere chart of 1515. Dürer numbered these stars from 3 to 8 in the order in which they were listed in the Almagest. (Stars 1 and 2 lay under the tail of the bear, at upper right of this illustration, and were the basis of Hevelius’s Canes Venatici.) Star 3 is the present-day Alpha Lyncis, star 4 is 38 Lyncis, and star 8 is 31 Lyncis. The identity of stars 5, 6, and 7 is uncertain, but could be the present-day 10 Ursae Majoris, 35 Lyncis, and 34 Lyncis misplaced by ten degrees. Dürer’s chart shows the constellations back to front, as they would appear on a celestial globe.