Genitive: Monocerotis

Abbreviation: Mon

Size ranking: 35th

Origin: Petrus Plancius

The mythical single-horned beast, the unicorn, is represented by this constellation which was unknown to the ancient Greeks. Monoceros was introduced in 1612 under the name Monoceros Unicornis on a globe by the Dutch theologian and cartographer Petrus Plancius. This was the same globe on which Camelopardalis, another of his inventions, first appeared.

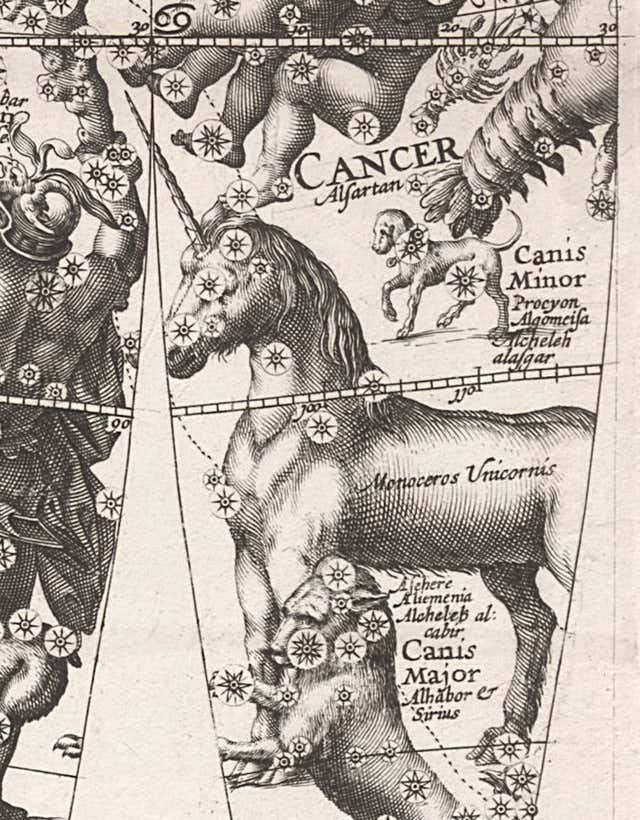

In 1624 the German astronomer Jacob Bartsch depicted it under the name Unicornu (sic) on a star chart in his book Usus Astronomicus Planisphaerii Stellati and as a result he was sometimes wrongly credited with its invention. In his book, Bartsch pointed to several passages in the Bible that supposedly mention unicorns, although these are now regarded as mistranslations. It is not clear whether Plancius introduced the constellation because of these Biblical references, but the unicorn has long been regarded as a Christian symbol of purity. The Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius adopted Monoceros in his influential star atlas and catalogue published in 1690 which ensured its acceptance by other astronomers.

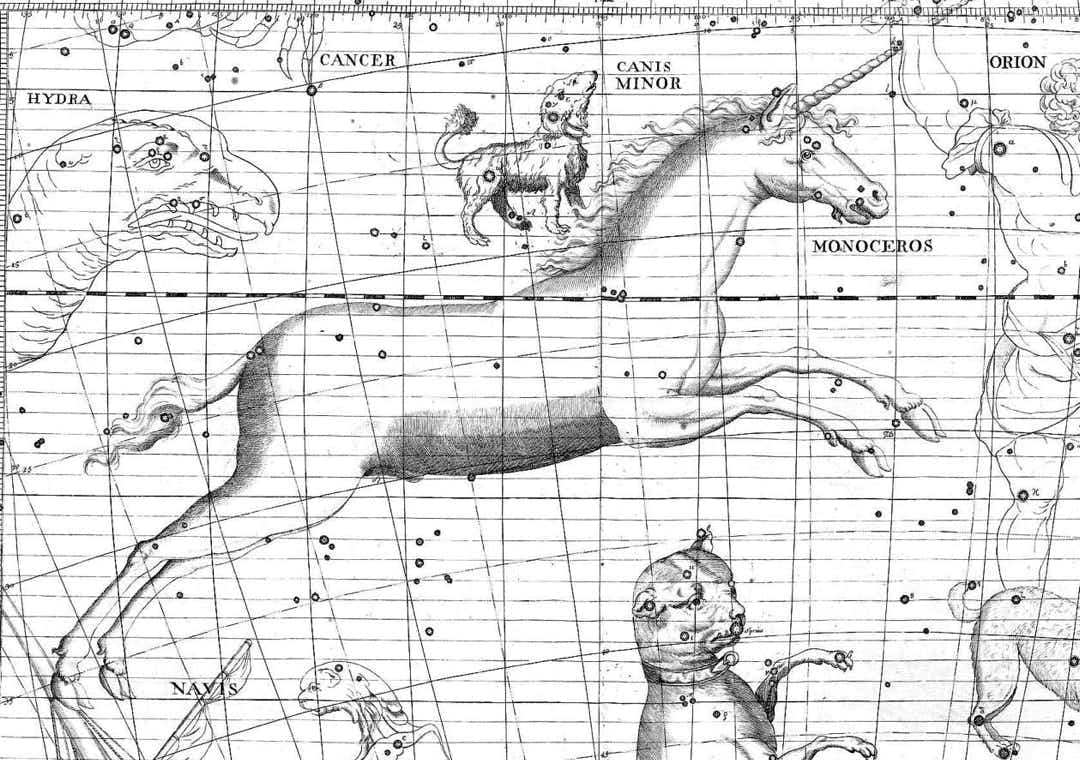

Monoceros prances between Canis Major (below it) and Canis Minor (above)

on the Atlas Coelestis of John Flamsteed (1729).

Its six brightest stars were allocated Greek letters by the American astronomer Benjamin Apthorp Gould in his Uranometria Argentina catalogue of 1879. However, by modern measurements, Beta Monocerotis is brighter than Alpha, so this is another constellation in which Alpha is not the brightest star. (An earlier attempt at lettering by the English astronomer Francis Baily in his British Association Catalogue of 1845 was a failure; through an oversight, he missed out the letters Alpha and Beta, and gave the letter Gamma to the star that became Gould’s Alpha.)

Monoceros fills a large area between Hydra and Orion where there was no Greek constellation. It is not prominent (its brightest stars are of fourth magnitude) but it lies in the Milky Way and contains a host of fascinating objects, most notably the Rosette Nebula, a wreath-shaped mass of glowing gas with embedded stars.

There are no legends associated with the constellation, as it is a modern figure, and none of its stars has a name.

Depictions of the unicorn

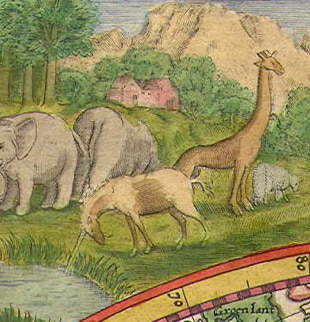

Plancius had already shown the unicorn and giraffe together in one corner of his world map of 1594 (detail below) which depicted animals from Asia; they appear with some elephants, plus what appears to be a fat-tailed sheep, and, further to the right, some dromedaries.

The unicorn dipping its horn in a stream, seen on the illustrations

surrounding a world map by Plancius dated 1594.

The posture of the unicorn, dipping its horn into a stream to purify it for the other animals, is reminiscent of a scene from the Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries, woven in the southern Netherlands around a century earlier, which Plancius could well have seen. However, in the sky, the unicorn is imagined not bending but with head and horn held high. Perhaps the presence of Canis Minor and Canis Major in the sky reminded Plancius of the dogs surrounding the unicorn in this attack scene from the Hunt tapestries. In addition, he might have seen further connections between sky and tapestry with the proximity of a hunter (Orion) and a river (Eridanus).

Chinese associations

Chinese astronomers were adept at creating constellations from faint stars, but even they struggled in Monoceros. A chain of four stars consisting of 8, 13, and 17 Monocerotis plus one in southern Gemini formed Sidu, representing the four major rivers of China (Yangtze, Yellow, Huai, and Si). Delta Monocerotis and one other star, probably 18 Mon, formed Queqiu, representing two hillocks either side of a gateway to the palace. According to Sun and Kistemaker (1997) Alpha Monocerotis was part of Tiangou, a guard dog, most of which lay in northern Puppis; other sources, though, place Tiangou farther south. Beta and Gamma Monocerotis seem not to have featured in any Chinese constellation.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

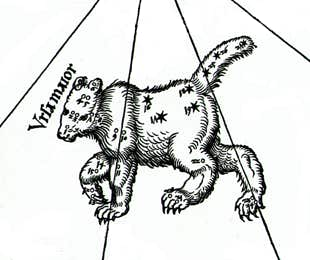

Monoceros made its first appearance on this gore for the 1612 celestial globe by Petrus Plancius and the Dutch engraver and cartographer Pieter van den Keere (Petrus Kaerius) (1571–c.1646). Being on a globe, the constellations are drawn in reverse from the way they appear in the sky.

In his book Usus Astronomicus Planisphaerii Stellati of 1624, Jacob Bartsch pointed out several passages in the Bible which mention unicorns:

Deuteronomy 33: ‘his horns are like the horns of unicorns’

Psalm 22: ‘Save me from the lion's mouth: for thou hast heard me from the horns of the unicorns.’

Isaiah 34: ‘And the unicorns shall come down with them’

Job 39: ‘Will the unicorn be willing to serve thee’

Modern versions of the Bible replace the word ‘unicorn’ with ‘wild ox’.