Genitive: Muscae

Abbreviation: Mus

Size ranking: 77th

Origin: The 12 southern constellations of Keyser and de Houtman

A small constellation to the south of Crux, the Southern Cross. Musca was one of the 12 southern constellations introduced at the end of the 16th century by Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman from the stars they observed during the first Dutch expeditions to the East Indies. The constellation arose because the seafarers saw chameleons eating flies during their stopover on Madagascar, and in the sky the fly lies next to the constellation Chamaeleon. These new southern constellations were first depicted by their fellow Dutchman Petrus Plancius on his globe of 1598, but for some reason he left the fly unnamed. In de Houtman’s catalogue of 1603, completed after Keyser’s death, it is called De Vlieghe, Dutch for fly.

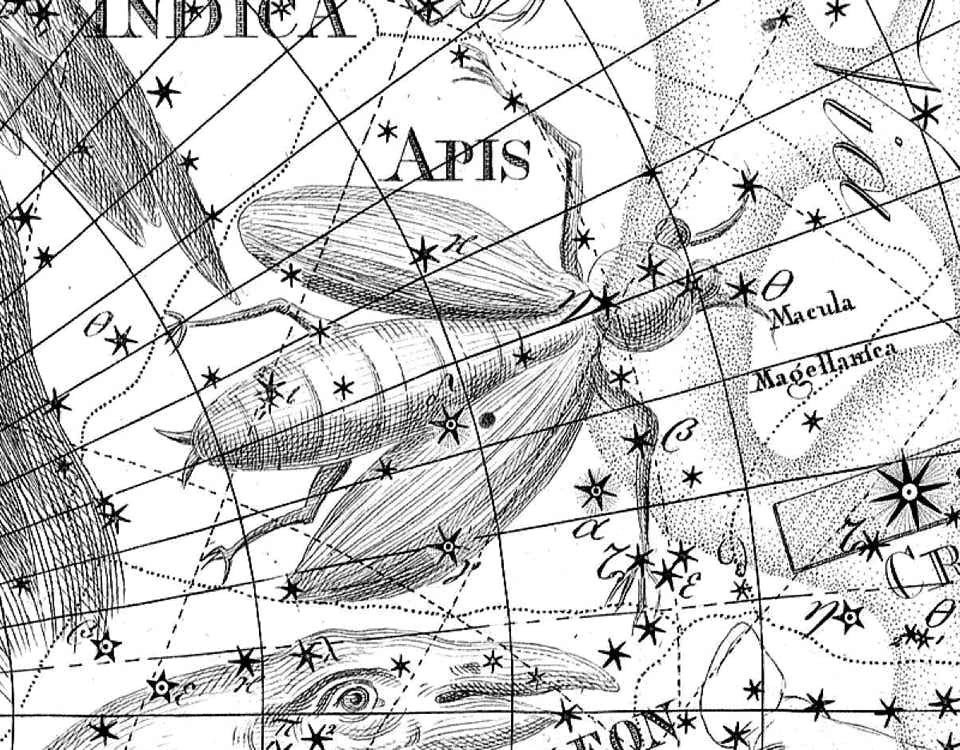

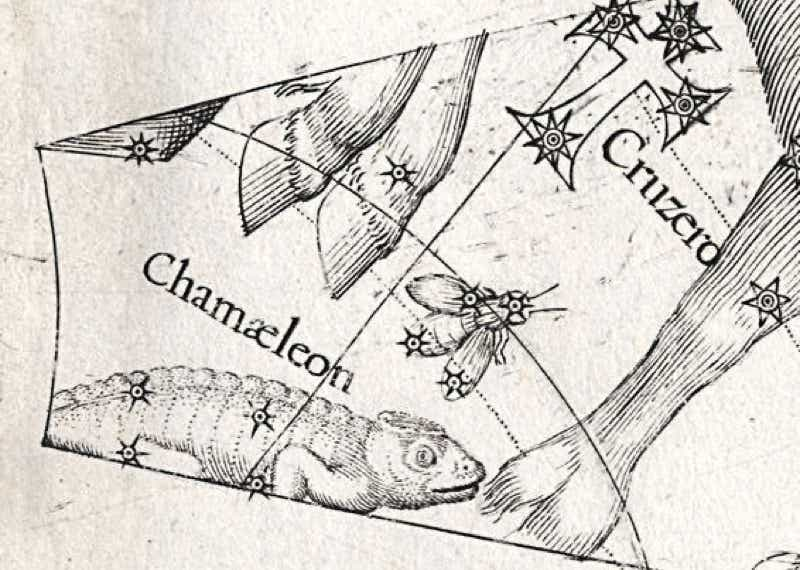

Johann Bayer, also in 1603, showed the insect on his plate of the 12 new southern constellations in Uranometria but called it Apis, the bee, an alternative title that was widely used for two centuries. The Dutch historian Elly Dekker believes that this alternative identification arose because Bayer copied his southern constellations from globes produced by Jodocus Hondius (1563–1612) in 1600 and 1601, on which the figure was left unnamed. Not knowing what it was meant to depict, Bayer wrongly identified it as a bee (apis), not a fly (musca).

Musca, shown under its sometime alternative name of Apis, the bee, on Chart XX of the Uranographia of Johann Bode (1801). Below it is the head of Chamaeleon, the chameleon, while to its right it overlaps the Coalsack Nebula, here named Macula Magellanica, most of which lies in Crux.

The French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille correctly identified the insect as a fly (calling it la Mouche) on his southern planisphere of 1756, but despite this Johann Bode, in his Uranographia of 1801, followed Bayer’s erroneous identification of it as Apis, the bee, as shown on the illustration above.

The first known use of the Latin name Musca for this constellation was in 1602 on a globe by Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571–1638), another Dutch cartographer and rival to Plancius. Plancius himself did not adopt a name for the constellation until 1612, when he called it Muia, the Greek for fly, on a globe produced that year. For a time it was known as Musca Australis, when there was also a northern fly, Musca Borealis, in the sky.

The constellation’s brightest star, Alpha Muscae, is of third magnitude.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

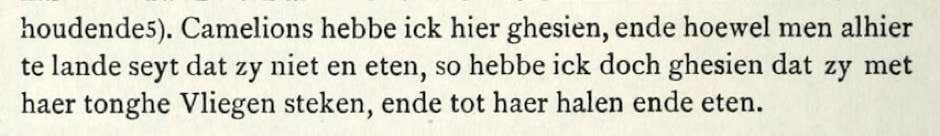

In Willem Lodewyckz’s account of the first Dutch trading expedition to the East Indies, De eerste schipvaart der Nederlanders naar Oost-Indië (1598), he wrote: ‘Camelions hebbe ick hier ghesien, ende hoewel men alhier te lande seyt dat zy niet en eten, so hebbe ick doch ghesien dat zy met haer tonghe Vliegen steken, ende tot haer halen ende eten,’ which in English is, ‘I saw chameleons here and although the locals claim that they never eat anything, I saw that they flick their tongues at flies which they thus catch and eat.’ Thanks to Rob van Gent for the translation.

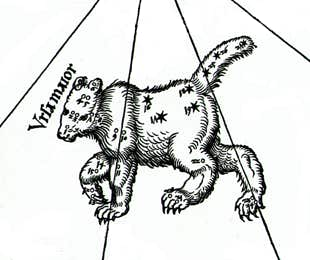

The chameleon and the fly depicted on a gore from Plancius’s celestial globe of 1598. The fly was unnamed, and remained so until Willem Janszoon Blaeu named it Musca on his globe of 1602. Johann Bayer, though, mistakenly dubbed it Apis, the bee, on his Uranometria atlas of 1603. (Nicolai Collection of the State Library of Württemberg, Stuttgart)