STORYTELLING is one of the most engaging of human arts, and what greater inspiration to a storyteller’s imagination than the stars of night. My interest in star tales has its roots in a series of skywatching guides that I produced in conjunction with the great Dutch celestial cartographer Wil Tirion. As I came to describe each constellation, I found myself wondering about its origin and the way in which ancient people had personified it in mythology.

Astronomy books did not contain satisfactory answers; they either gave no mythology at all, or they recounted stories that, I later discovered, were not true to the Greek originals. In addition, many authors seemed unaware of the true originators of several of the constellations introduced since ancient Greek times. I decided, therefore, to write my own book on the history and mythology of the constellations, and a fascinating undertaking it proved to be. I have now transferred it to the web where I continue to expand it.

My theme has been how Greek and Roman literature has shaped our perception of the constellations as we know them today – for, surprisingly enough, the constellations recognized by 21st-century science are primarily those of the ancient Greeks, interspersed with more recent additions. To this end, I have gone back to original Greek and Latin sources wherever possible; click here for a list of sources and references. While I have attempted to recount the main variants of each myth, and to identify the writer concerned, it should be realized that there is no such thing as a ‘correct’ myth; for some stories, there are almost as many different versions as there are mythologists.

I have not tried to compare the Greek and Roman constellations with the constellations that were imagined by other cultures, with one exception – that of China. Now that modern studies are furnishing us with a better understanding of ancient Chinese constellations, I have added notes about them in this web edition. However, Chinese constellations were far more malleable in size, shape, and position than western ones. They were not mythological but expressed aspects of real life, so their names and symbolism varied with time as Chinese society developed and the ruling dynasty changed; hence a given constellation could be interpreted in more than one way, and sometimes a constellation name was transferred to completely different stars.

Neither have I delved too far into the confusing morass of speculation about when and where the very first constellations originated. Indeed we may never be able to provide convincing answers from the fragmentary information available.

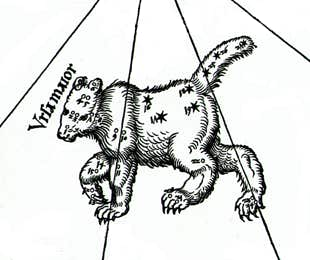

Since ancient astronomers regarded each constellation as embodying a picture of a mythological character or an animal, rather than as simply an area of sky as defined by today’s surveyor-astronomers, it seemed natural to illustrate each constellation with a picture from an old star map. These star maps are works of art in themselves, and are among the most elegant treasures bequeathed to us by astronomers of the past. The constellations give us a very real link with the most ancient civilizations. Constellation history and mythology is classified by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage. It is a heritage that we can share whenever we look at the night sky.

Ian Ridpath

Glossary

The Greeks and Romans had similar gods and mythological characters, but used

different names for them. Hence what may sound at first to be two different

characters, such as Zeus and Jupiter, are really one and the same.

This table lists the Latin equivalents (in italics) of the major Greek characters mentioned in Star Tales.

Greek name

Aphrodite

Artemis

Athene

Demeter

Eros

Hephaestus

Heracles

Persephone

Poseidon

Latin name

Venus

Diana

Minerva

Ceres

Cupid

Vulcan

Hercules

Proserpina

Neptune

Greek name

Ares

Asclepius

Cronos

Dionysus

Hades

Hera

Hermes

Polydeuces

Zeus

Latin name

Mars

Aesculapius

Saturn

Bacchus

Pluto

Juno

Mercury

Pollux

Jupiter