TAURUS CONTINUED »

The Pleiades – seven celestial sisters

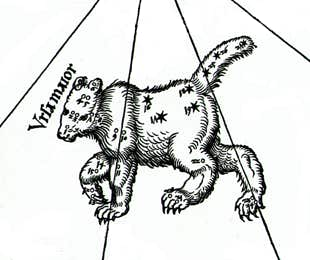

Even more famous than the Hyades is another star cluster in Taurus: the Pleiades (Πλειάδες in Greek), commonly known as the Seven Sisters. The Pleiades lie about 440 light years away, nearly three times the distance of the Hyades. To a casual glance, the Pleiades cluster appears as a fuzzy patch like a swarm of flies over the back of the bull. According to Hyginus, some ancient astronomers called them the bull’s tail.

So distinctive are the Pleiades that the ancient Greeks regarded them as a separate mini-constellation and used them as a calendar marker. Hesiod, in his agricultural poem Works and Days, instructs farmers to begin harvesting when the Pleiades rise at dawn, which in Greek times would have been in May, and to plough when they set at dawn, which would have been in November. The Arabs called the Pleiades al-Thurayyā, a female name referring to something small but abundant; an alternative Arabic name was al-Najm, meaning simply ‘the Star’, in the singular.

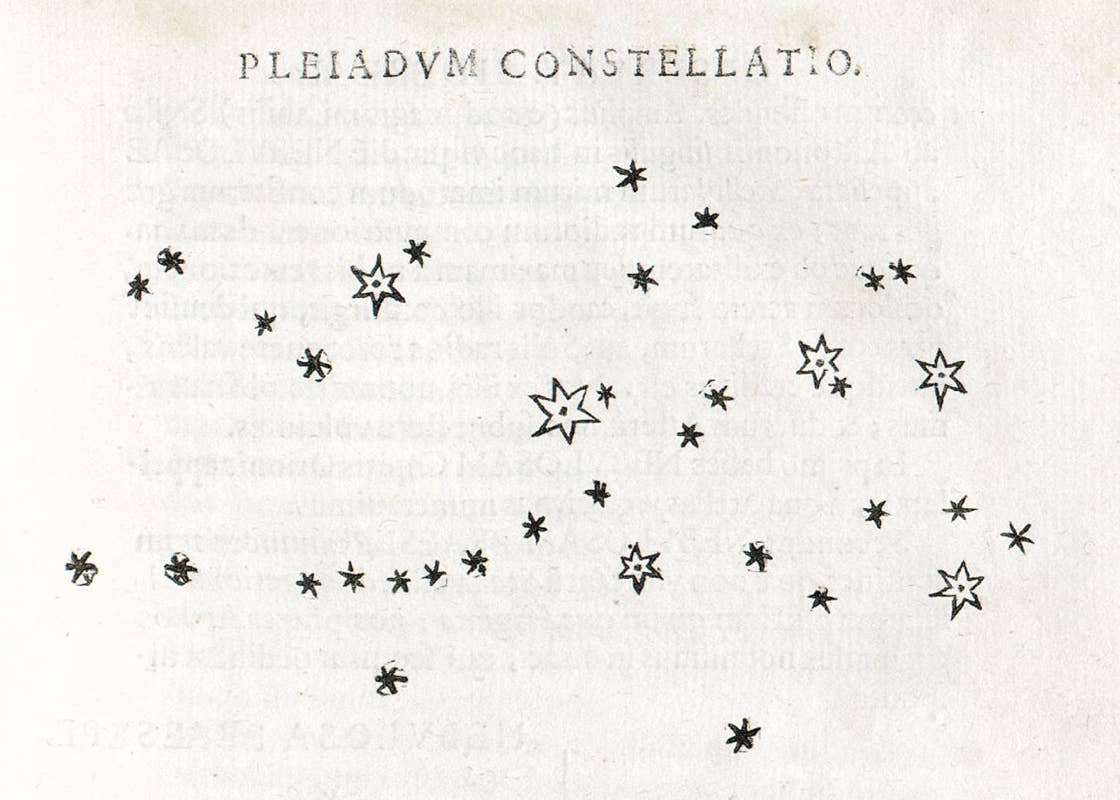

Ptolemy listed three stars of the Pleiades in his Almagest (probably Taygeta, Electra, and Atlas), outlining the overall size and shape of the cluster, plus what he termed a ‘small star’ over a degree to the north, probably 5th-magnitude HR 1188. The 10th-century Persian astronomer al-Ṣūfī recorded three more stars within the cluster (probably Alcyone, Maia, and Merope) and compared the group to a bunch of grapes. The first telescopic view of the Pleiades was by Galileo, who published a sketch showing six naked-eye stars and thirty fainter ones in his book Sidereus Nuncius in 1610.

In Greek mythology the Pleiades were the seven daughters of Atlas and the oceanid Pleione, after whom they are named. One popular derivation is that the name comes from the Greek word plein, meaning ‘to sail’ – so Pleione means ‘sailing queen’ and the Pleiades are the ‘sailing ones’, because in Greek times they were visible all night during the summer sailing season. When the Pleiades vanished from the night sky, it was considered prudent to remain ashore. ‘Gales of all winds rage when the Pleiades, pursued by violent Orion, plunge into the clouded sea’, wrote Hesiod. Alternatively, and possibly more likely, the name may come from the old Greek word pleos, ‘full’, which in the plural meant ‘many’, a suitable reference to the cluster. According to other authorities, the name comes from the Greek word peleiades, meaning ‘flock of doves’.

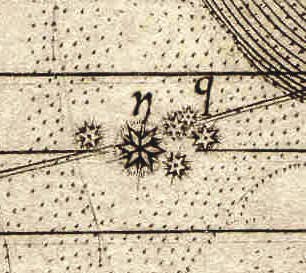

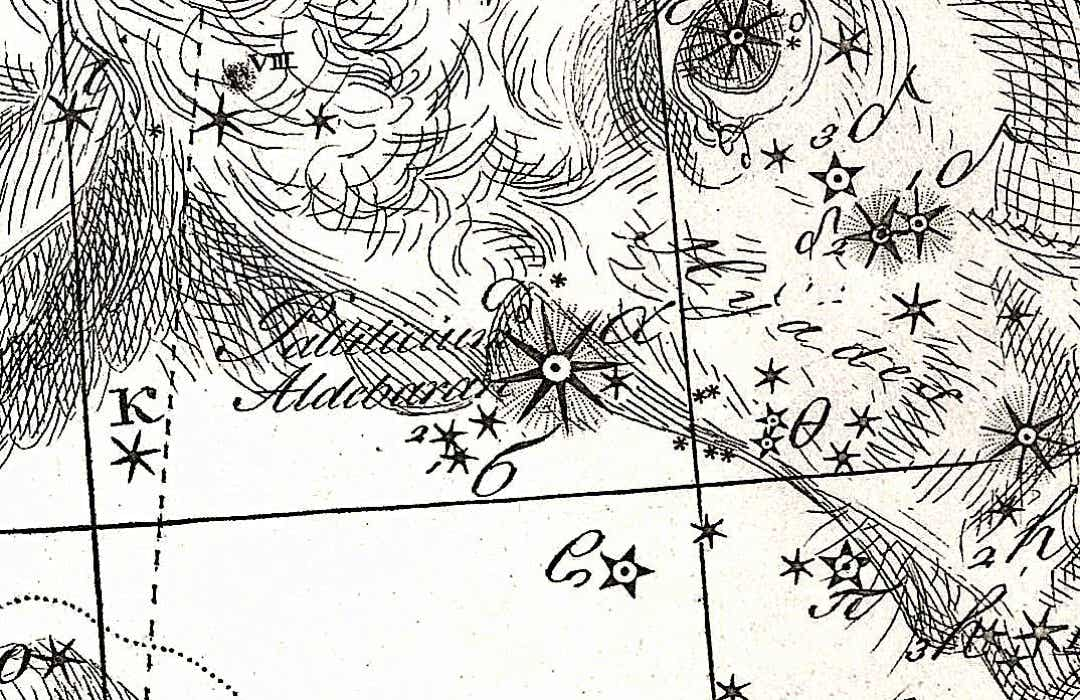

Johann Bayer showed the six brightest members of the Pleiades on his Uranometria atlas of 1603: Atlas, Alcyone, Merope, Maia, Taygeta, and Electra. The star marked with the Greek letter Eta (η) on the chart is Alcyone, magnitude 2.9, which Bayer described as Lucida Pleiadum (the brightest Pleiad) in his accompanying catalogue. Another star is labelled with a lowercase letter q. This is Taygeta, magnitude 4.3, which Bayer called Pleiadum minima, i.e. the faintest Pleiad.

A famous myth links the Pleiades with Orion. As Hyginus tells it, Pleione and her daughters were one day walking through Boeotia when Orion tried to ravish her. Pleione and the girls escaped, but Orion pursued them for seven years. Zeus immortalized the chase by placing the Pleiades in the heavens where Orion follows them endlessly.

Names of the Pleiades

Unlike their half-sisters the Hyades, the names of all seven Pleiades are assigned to specific stars in the cluster: Alcyone (the brightest, at magnitude 2.9), Asterope, Celaeno, Electra, Maia, Merope, and Taygeta. Two more stars are named after their parents, Atlas and Pleione. These names were not given to the stars by the Greeks, but were added in post-telescopic times once the stars could be more clearly distinguished.

The first catalogue to allocate individual names to stars in the Pleiades seems to have been that of the Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli (1598–1671) in his book Astronomiae Reformatae of 1665.[note] For his positions of the Pleiades stars Riccioli used observations by the Mallorcan astronomer Vicente Mut (1614–87) and the Dutch astronomer Michael van Langren (1598–1675). Riccioli did not make it clear which of them was responsible for naming the seven main members, but credited van Langren with adding the names Atlas and Pleione. Neither Hevelius nor Flamsteed took any notice of these new names when compiling their own catalogues, but they were picked up by Johann Bode in his Allgemeine Beschreibung und Nachweisung der Gestirne catalogue of 1801, and also by Giuseppe Piazzi in his Palermo Catalogue of 1814, after which they became firmly established.

According to mythology, Alcyone and Celaeno were both seduced by Poseidon. Maia, the eldest and most beautiful of the sisters, was seduced by Zeus and gave birth to Hermes; she later became foster-mother to Arcas, son of Zeus and Callisto. Zeus also seduced two others of the Pleiades: Electra, who gave birth to Dardanus, the founder of Troy; and Taygeta, who gave birth to Lacedaemon, founder of Sparta. Asterope was ravished by Ares and became mother of Oenomaus, king of Pisa, near Olympia, who features in the legend of Auriga. Hence six Pleiades became paramours of the gods. Only Merope married a mortal, Sisyphus, a notorious trickster who was subsequently condemned to roll a stone eternally up a hill.

The ‘missing’ Pleiad

Although the Pleiades are popularly termed the Seven Sisters, only six stars are easily visible to the naked eye, and a considerable mythology has grown up to account for the ‘missing’ Pleiad. Eratosthenes says that Merope was the faint Pleiad because she was the only one who married a mortal. Hyginus and Ovid also recount this story, giving her shame as the reason for her faintness, but both add another candidate: Electra, who could not bear to see the fall of Troy, which had been founded by her son Dardanus. Hyginus says that, moved by grief, she left the Pleiades altogether, but Ovid says that she merely covered her eyes with her hand. Astronomers, however, have not followed either legend in their naming of the stars, for the faintest named Pleiad is actually Asterope.

Binoculars show dozens of stars in the Pleiades, and in all the cluster contains a hundred or so members. They are relatively youthful by stellar standards, the youngest being no more than a few million years old. Long-exposure photographs show a haziness around the stars which was once thought to be the remains of the cloud from which the stars formed. But that should all have dispersed long ago, so it now seems that all this haziness is an entirely unrelated cloud that the stars happen to be drifting through as they move through space.

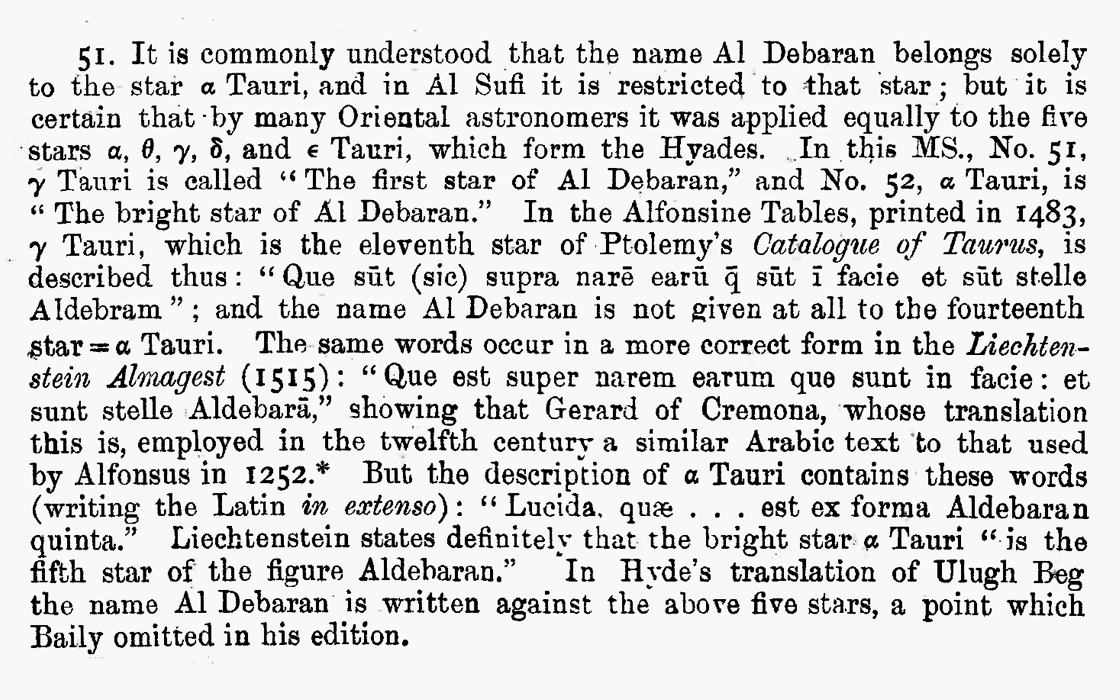

Aldebaran, the eye of the bull

The bull’s glinting red eye is marked by the brightest star in Taurus, Aldebaran, a name that comes from the Arabic al-dabarān meaning ‘the follower’ because it follows the Pleiades across the sky. It was also known in Arabic as ‘Ain al-Thaur (the eye of Taurus) and al-Fanīq, the large or male camel; in this latter interpretation the stars of the Hyades were al-Qilāṣ, the small camels. Some Arabic astronomers applied the name Aldebaran to the Hyades as a whole.

An alternative Latin name was Palilicium, which came about because the star disappeared in twilight around the time of the festival of Pales, the Roman god of shepherds, on April 21. Flamsteed used this name in his star catalogue but was inconsistent in his spelling, writing both Palilicium and Pallilicium (i.e. with a single and a double ‘l’). Johann Bode gave it on his chart of Taurus as Pallilicium (with a double l).

Surprisingly for such a prominent star, Greek astronomers had no name for it (although Ptolemy called it Torch in his Tetrabiblos, a book about astrology). Aldebaran appears to be a member of the Hyades but in fact is a foreground object at less than half the distance, and so is superimposed on the Hyades by chance. Aldebaran marks the right eye of the bull; the left eye is represented by Epsilon Tauri, with Gamma Tauri on the nose.

The horns – and a nebula named the Crab

At the tip of the bull’s left horn is Beta Tauri, or Elnath, a name that comes from the Arabic al-Nāṭiḥ meaning ‘the butting one’. Ptolemy described this star as being common with the right foot of Auriga, the Charioteer, but since the introduction of rigorously defined constellation boundaries in 1930 it is now the exclusive property of Taurus. Hence the bull has kept the tip of his horn, but the charioteer has lost his right foot.

Near the tip of the bull’s right horn, which is marked by Zeta Tauri, lies the remarkable Crab Nebula, the result of one of the most celebrated events in the history of astronomy – a stellar explosion, seen from Earth in AD 1054, that was bright enough to be visible in daylight for three weeks. We now know this this event was a supernova, the violent death of a massive star, and the Crab Nebula is the shattered remnant of the star that blew up, now visible only through telescopes.

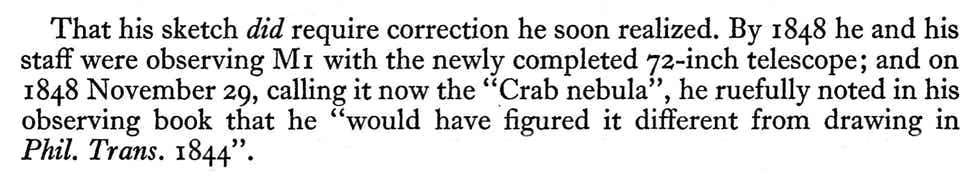

The nebula was discovered in 1731 by the English astronomer John Bevis (1695–1771) and was first shown on Chart 23 of his Uranographia Britannica star atlas of c.1750 which, sadly, remained unpublished because his printer went bankrupt. It was rediscovered 27 years later by the Frenchman Charles Messier who made it the first entry in his famous list of nebulous objects; hence it is commonly known as M1. The name Crab Nebula arose after the Irish astronomer Lord Rosse (1800–67) published a drawing of it in 1844 as seen through his 36-inch reflector which showed it with claw-like arms.

Chinese associations

In Chinese astronomy the Pleiades star cluster was known as Mao and was said to represent a hairy head – the head of who or what is unexplained, although the idea of hairiness might come from the cluster’s hazy appearance. Mao is also the name of the 18th lunar mansion.

The V-shaped Hyades cluster was called Bi, depicting a net with a long handle for catching animals such as rabbits (Lambda Tauri was the end of the handle). Bi gave its name to the 19th lunar mansion. In a very different visualization, Bi was also seen as a regiment of soldiers guarding the frontier regions, with Aldebaran as their commanding general. Both the lunar mansions Mao and Bi were the subjects of extensive astrological lore. (Confusingly, the 14th mansion, in Andromeda and Pegasus, is also called Bi but with a different meaning.)

A star just south of the Hyades, usually identified as Sigma Tauri, was Fuer, ‘whisper’, possibly referring to someone who has the ear of the Emperor or perhaps a scout indicating the presence of animals for catching in the net. Straddling the ecliptic between the Pleiades and Hyades lay Tianjie, ‘celestial street’, consisting of Kappa and Omega Tauri, apparently representing the route used by the Emperor when he went hunting. The fourth-magnitude star 37 Tauri nearby was known as Yue, the Moon star; it lies on the opposite side of the sky from the Sun star, Ri, in Libra, reflecting the fact that when the Moon is full it lies opposite the Sun in the sky. In ancient times, the full Moon in Bi signalled the start of the rainy season in China. To the north of Tianjie and Yue a group of four stars (some say five), including Chi and Psi Tauri, formed Lishi, a whetstone for sharpening blades.

Zeta Tauri was Tianguan, representing a gate or door on the ecliptic even though it is only a single star. It lay directly opposite in the sky to Tianyue in Sagittarius and Ophiuchus, which represented a lock or keyhole on the ecliptic. Beta Tauri to the north was one of the five chariots of the celestial emperors, Wuche, the others being in Auriga. A line of six stars running almost parallel to the ecliptic from 136 to Tau Tauri formed Zhuwang, six sons of the Emperor.

Between Zeta Tauri and the Hyades lay Tiangao, a group of four stars including Iota Tauri, representing a lookout tower for weather watching (although another interpretation sees it as a place to make offerings to the gods); the observers were Siguai, consisting of 139 Tauri plus two stars in Orion and one in Gemini.

To the south of the Hyades lay a second constellation whose Chinese name transliterates as Tianjie. This one consisted of eight stars and is said to represent a token carried by ambassadors to identify themselves when leaving the country; however, Sun and Kistemaker suggest Tianjie was the regalia of the great hunter Shen, the Chinese equivalent of Orion. On the border between Taurus and Cetus was Tianlin, four stars (Omicron, Xi, 4, and 5 Tauri) representing a storehouse for millet or rice.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

Galileo’s sketch of the Pleiades from his book Sidereus Nuncius published in March 1610. The six brightest stars, depicted with larger symbols, are: Atlas (upper left); Alcyone (the brightest and hence the largest symbol of all); Merope (lower left); Maia (upper centre); Taygeta (upper right); and Electra (lower right). In his accompanying text Galileo described the Pleiades as a cluster of six stars, noting that the seventh one was almost never visible; this suggests that his eyesight was not particularly good.

Riccioli had previously given a written description of the Pleiades in his Almagestum Novum of 1651 in which he referred to the brightest star of the cluster (the lucida) as Maia. His later list in the Astronomiae Reformatae renamed the brightest star Alcyone, and that is the list of names we know today.

The English astronomical historian E. B. Knobel described how the name Aldebaran was used by the Arabs for the entire Hyades cluster in a paper published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1895, pp. 436–7.

Oddly, Rosse seemed to think that the object was a cluster, not a nebula, perhaps because he was able to resolve faint stars which lay in the foreground but were not actually part of the Nebula itself. The origin of the name Crab may be due at least in part to Thomas Romney Robinson, director of Armagh Observatory, who observed M1 with Rosse in 1840 and described it as having ‘streams running out like claws in every direction’.