Genitive: Aurigae

Abbreviation: Aur

Size ranking: 21st

Origin: One of the 48 Greek constellations listed by Ptolemy in the Almagest

Greek name: Ἡνίοχος (Heniochos)

High in the northern sky stands a forlorn-looking charioteer. With his right hand he grasps the reins of a chariot and a whip, while on his left arm he carries a goat and its two kids. Of his chariot itself there is no sign. What’s the story here? Mythology offers several identifications for this prominent constellation, although the presence of the goat is not accounted for by any of them.

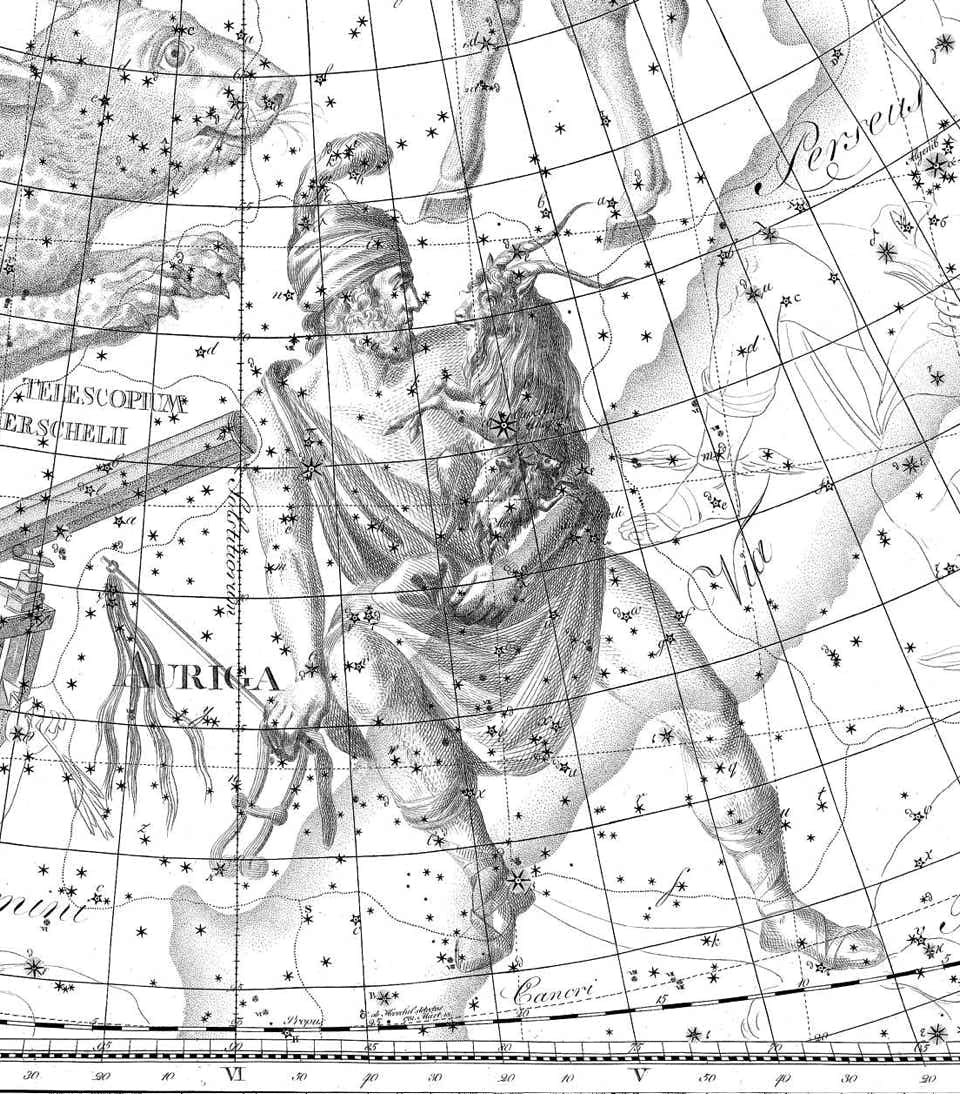

Auriga carrying the goat and kids, seen on Chart V of the Uranographia of

Johann Bode (1801).The bright star Capella lies in the body of the goat, while its two kids are cradled on the charioteer’s forearm. The now-obsolete constellation of Telescopium Herschelii intrudes from the left.

Is it Erichthonius…

The most popular interpretation is that he is Erichthonius, a legendary king of Athens. Erichthonius was the son of Hephaestus the god of fire, better known by his Roman name of Vulcan. Hephaestus was too busy smithying to be bothered with his son, who was instead raised by the goddess Athene, after whom the city of Athens is named. When he grew up, Erichthonius instituted a festival called the Panathenaea in her honour.

Athene taught Erichthonius many skills, including how to tame horses. He became the first person to harness four horses to a chariot, in imitation of the four-horse chariot of the Sun (the quadriga), a bold move which earned him the admiration of Zeus and assured him a place among the stars. There, according to this story, Erichthonius is depicted at the reins, perhaps participating in the Panathenaic games in which he frequently drove his chariot to victory.

…or Myrtilus…

Another identification is that Auriga is really Myrtilus, the charioteer of King Oenomaus of Pisa and son of Hermes. The king had a beautiful daughter, Hippodamia, whom he was determined not to let go. He challenged each of her suitors to a death-or-glory chariot race. They were to speed away with Hippodamia on their chariots, but if Oenomaus caught up with them before they reached Corinth he would kill them. Since he had the swiftest chariot in Greece, skilfully driven by Myrtilus, no man had yet survived the test.

A dozen suitors had been beheaded by the time that Pelops, the handsome son of Tantalus, came to claim Hippodamia’s hand. Hippodamia, falling in love with him on sight, begged Myrtilus to betray the king so that Pelops might win the race. Myrtilus, who was himself secretly in love with Hippodamia, tampered with the pins holding the wheels on Oenomaus’s chariot. During the pursuit of Pelops, the wheels of the king’s chariot fell off and Oenomaus was thrown to his death.

Hippodamia was now left in the company of both Pelops and Myrtilus. Pelops solved the awkward situation by unceremoniously casting Myrtilus into the sea, from where he cursed the house of Pelops as he drowned. Hermes put the image of his son Myrtilus into the sky as the constellation Auriga. Germanicus Caesar supports this identification because, he says, ‘you will observe that he has no chariot, and, his reins broken, is sorrowful, grieving that Hippodamia has been taken away by the treachery of Pelops’.

…or Hippolytus?

A third identification of Auriga is Hippolytus, son of Theseus, whose stepmother Phaedra fell in love with him. When Hippolytus rejected her, she hanged herself in despair. Theseus banished Hippolytus from Athens. As he drove away his chariot was wrecked, killing him. Asclepius the healer brought the blameless Hippolytus back to life again, a deed for which Zeus struck Asclepius down with a thunderbolt at the demand of Hades, who was annoyed at losing a valuable soul.

Aratus did not identify the constellation with any character. He simply called it Ἡνίοχος (Heniochos), the charioteer, as did Ptolemy in the Almagest. From this Greek name comes the Latin transliteration Heniochus, used for the constellation by some Roman writers such as Manilius.

The aegis of Zeus

An alternative story is that Amaltheia was not the goat itself but the nymph who owned the goat. Eratosthenes says that the goat was so ugly that it terrified the Titans who ruled the Earth at that time. When Zeus grew up he challenged the Titans for supremacy. Following the advice of an oracle he skinned the goat and made a cloak from its impenetrable hide, the back of which resembled the head of a Gorgon. This horrible-looking goatskin formed the so-called aegis of Zeus (the word aegis actually means ‘goatskin’). The aegis protected Zeus and scared his enemies, a particular advantage in his fight against the Titans. Afterwards Zeus covered the bones of the goat in a normal-looking skin and transformed it into the star Capella.

The she-goat and kids

Auriga contains the sixth-brightest star in the sky, known as Capella, a Roman name meaning ‘she-goat’; the Greeks called it Αἲξ (Aix), meaning the same. Ptolemy in the Almagest described this star as being on the charioteer’s left shoulder, but all major star atlases, including those of Bayer, Flamsteed, and Bode (above), have shown it in the body of the goat. According to Aratus it represented the goat Amaltheia, who suckled the infant Zeus on the island of Crete and was placed in the sky as a mark of gratitude, along with the two kids she bore at the same time. The Arabic name for Capella, al-‘Ayyūq, may arise from an attempt to transliterate the Greek name Αἲξ. On Bode’s chart, above, it is given the alternative name Alhajoth, presumably a heavily corrupted version of the Arabic.

The kids, frequently known by their Latin name of Haedi (Greek: Ἔριφοι, i.e. Eriphoi), also spelled Hoedi as on Bode’s atlas, are represented by the neighbouring stars Eta and Zeta Aurigae; Ptolemy described them as lying on the charioteer’s left wrist. Hyginus credits the Greek astronomer Cleostratus with having first called these two stars the Kids in the 5th century BC. It is sometimes said that the variable star Epsilon Aurigae to the north of them is a third member of the kids, but this is incorrect – Ptolemy and the mythologists were clear that there were only two kids. According to Ptolemy, Epsilon Aurigae actually marks the charioteer’s left elbow.

Some early writers spoke of the Goat and Kids as a separate constellation, but since the time of Ptolemy they have been awkwardly combined with the Charioteer, the goat resting on the charioteer’s shoulder, with the kids supported on his forearm. There is no legend to explain why the charioteer is so encumbered with livestock.

Other stars in Auriga

Beta Aurigae is popularly known as Menkalinan, a name that comes from the Arabic mankib dhī’l-‘inān, meaning ‘shoulder of the charioteer’, since it was described by Ptolemy as lying on the charioteer’s right shoulder.

Bayer in his Uranometria gave the Greek letter Psi (ψ) to a swarm of ten stars of 5th and 6th magnitudes that make up the charioteer’s whip. These stars, spanning over 10° in declination, were allocated the individual superscripts ψ1, ψ2, and so on by Argelander in his Uranometria Nova of 1843, although ψ10 is now just over the border in Lynx where it is known as 16 Lyncis. Bayer wrote that these stars were called βουπλῆγας in Greek, meaning a goad (R. H. Allen in his book Star Names mis-spelled the word βουλήγες), or dolones in Latin, with the same meaning.

A ‘shared’ star

Greek astronomers regarded one star as being shared by Auriga and Taurus. Ptolemy in the Almagest described this star as representing both the right foot of the charioteer and also the tip of the bull’s left horn. When the German astronomer Johann Bayer came to allocate Greek letters to the stars in the early 17th century he designated this star as both Gamma Aurigae and Beta Tauri. However, since the introduction of precise constellation boundaries in 1930, astronomers have assigned this star exclusively to Taurus as Beta Tauri and there is no longer a Gamma Aurigae. Hence, under the modern scheme, the bull has kept the tip of his horn but the luckless charioteer has lost his right foot.

Chinese associations

In the Chinese constellation system, the four main stars of Auriga – Alpha (Capella), Beta, Theta, and Iota Aurigae – plus the present-day Beta Tauri formed Wuche or Wuju, meaning five chariots, one for each of the five celestial emperors. These stars were also said to govern the harvest of the five main types of cereal grown in China at that time.

The prominent triangle near Capella formed by the stars Epsilon, Zeta, and Eta Aurigae was one of three such triangles in and around Auriga that the Chinese termed Zhu or Sanzhu, poles for tethering the horses. The second triangle was formed by Tau, Nu, and Upsilon Aurigae, and the third by Chi, 26 Aurigae, and one other star, identity uncertain. Two other groups of stars within Wuche were known as Tianhuang and Xianchi, both representing ponds, although sources differ as to exactly which stars were involved in each group. Xianchi was said to be where the Sun bathed at the end of each day. Tianhuang has also been interpreted as a bridge or pier.

Nine stars scattered across eastern Auriga, in the charioteer’s whip between the Milky Way and the border with Lynx, formed Zuoqi, representing flags marking seats set out for the Emperor and his dignitaries, presumably for official functions. In the far north of Auriga, Delta and Xi formed part of Bagu, representing eight kinds of crops, most of which was over the border in Camelopardalis.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved