Ptolemy’s Almagest

First printed edition, 1515

THE first printed edition of Ptolemy’s Almagest was published in Venice in 1515. It is based on the Latin translation made by Gerard of Cremona (c. 1114–87) in Toledo, Spain, around 1175. Gerard worked from 9th-century Arabic translations from the Greek. Ptolemy’s original manuscript is thought to have been produced around AD 150 and was long lost by Gerard’s time, a thousand years later, but handwritten copies survived, both in Greek and in Arabic. Gerard’s Latin translation from Arabic was the version of the Almagest most widely used from the 12th century onwards, so it was natural that it should be the first to benefit from the invention of printing. It was followed in 1538 by the first printed edition in the original Greek.

In his catalogue, Ptolemy listed 1,028 objects forming the classical 48 constellations (see the table at bottom of the page). Three stars were deliberately entered twice, since Ptolemy regarded them as being shared between constellations, as follows. The star Ptolemy described as at the end of the flow of water from the urn of Aquarius was the same as the one in the mouth of Piscis Austrinus; this is the star we call Fomalhaut. The star on the right ankle of Auriga also marked the tip of the northern horn of Taurus; we know it as Beta Tauri. And the star at the top of the staff of Boötes is the same as the one on the right foot of Hercules; we call it Nu Boötis.

Reducing the total further, another three objects in Ptolemy’s catalogue are actually not stars at all: these are the Double Cluster in Perseus (NGC 869 and 884); M44 (Praesepe) in Cancer; and the globular cluster Omega Centauri. Hence it is usually said that the Almagest contains 1,022 stars. However, the stars 18 and 20 in Cetus are now thought to be duplicates of Cetus 17 and 19 (DIO, vol. 12, p. 62, 2002, section C26). So the total number of separate stars in the Almagest is actually 1,020. The number of stars Ptolemy catalogued in each constellation ranged from a mere two in Canis Minor to 45 in Argo Navis.

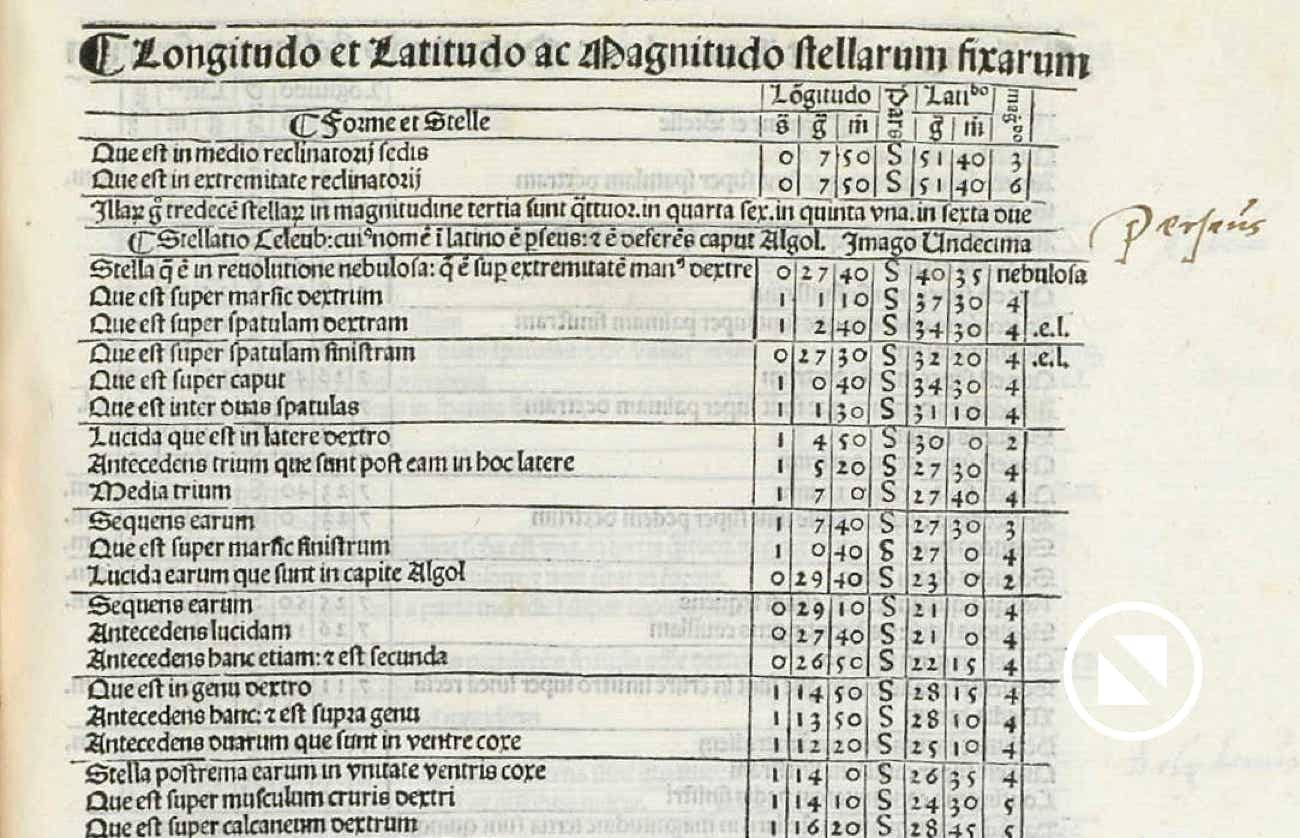

A page from the 1515 printing of the Almagest, showing the end of the star catalogue for Cassiopeia (top two lines) and the start of the listing of stars in Perseus. Note that the first entry in Perseus is described as ‘nebulosa’, i.e. nebulous. This is in fact the twin star cluster known as the Double Cluster, visible to the naked eye under clear, dark skies.

Part of a sample page is illustrated above. The top two lines contain the last two stars in the listing for Cassiopeia. Following these is a line totalling the number of stars catalogued in Cassiopeia, as Ptolemy did at the end of every constellation (the Latin reads ‘Thirteen stars: four of the third magnitude, six of the fourth, one of the fifth, two of the sixth’). Then comes the start of the entry for Perseus, but the printed heading is not prominent so the book’s owner has written ‘Perseus’ by hand in the margin to make it easier to pick out.

Each star’s longitude and latitude is listed, as is its brightness on a scale from 1 to 6, the same principle as the modern magnitude scale – although Ptolemy himself did not use numbers but Greek letters, with alpha for first magnitude, beta for second, and so on. The letter S in the column before the latitude stands for septentrionalis, meaning northern in Latin (the word is in reference to the seven stars of the Plough, which define the northern sky). The first entry in Perseus is described in the magnitude column as ‘nebulous’ – this is the famous Double Cluster in the right hand of Perseus.

Identifying stars

In the Almagest, Ptolemy identified stars not by letters or catalogue numbers, as we would do now, but by their position in the imaginary constellation figure. For example, Alpha Persei, the seventh star on the list, is described as ‘the bright star on the right side’ (‘Lucida que est in latere dextro’ in Latin), while the twelfth entry in this printed edition is called ‘Lucida earum que sunt in capita Algol’ (‘the bright one in the head of the Demon’). Here we see an Arabic influence in the translation, since Algol is an Arab name, which had crept into use since Ptolemy’s time; in the original Greek, Ptolemy had called this the Gorgon’s head, in line with Greek mythology.

Ptolemy mentioned only eleven star names in the Almagest, some of which have since been superseded by Latin or Arabic alternatives, as follows: Aetos, which we now know by the later Arabic name Altair; Aix, now known by the later Latin name Capella; Antares; Arcturus; Basiliskos, now known by the Latin name Regulus; Canopus (too far south for Aratus to have seen, but mentioned by Eratosthenes); Kyon (i.e. Sirius); Lyra, now known by the Arabic name Vega; Procyon; Protrygeter, now known by the Latin name Vindemiatrix; and Stachys, now known by the Latin name Spica. Surprisingly, some of the brightest stars in the sky including Aldebaran, Betelgeuse, and Rigel did not have names in Greek times, or if they did they were not mentioned by Ptolemy. For some reason Greek astronomers seem not to have been particularly bothered about naming individual stars.

‘Unformed’ stars

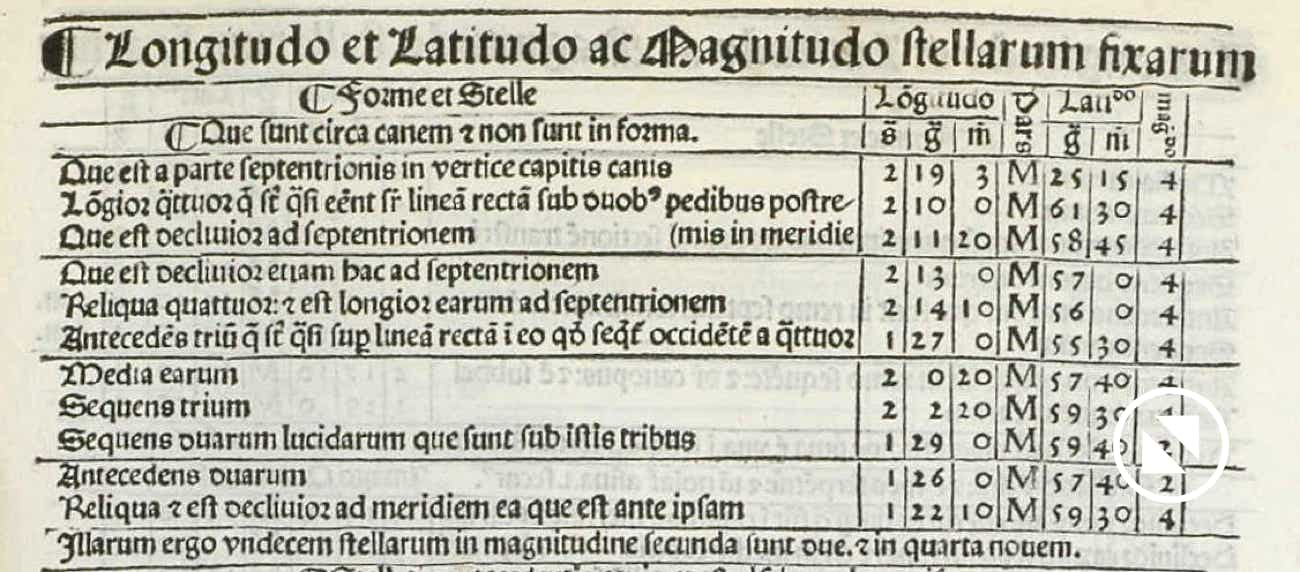

At the end of some constellations, Ptolemy listed what he called ἀμόρφωτοι, i.e. amorphotoi – ‘unformed’ stars (informatae in Latin) that lay outside the recognized constellation pattern. (In fact 108 stars in the Almagest – over 10% of the total – were categorized by Ptolemy as ‘unformed’.) Now that constellations are regarded as areas of sky rather than actual pictorial representations, most of these unformed stars have been absorbed into the related constellation or a neighbour. However, in some cases, later astronomers incorporated the orphan stars into new constellations. In the example shown below, Ptolemy lists 11 stars as lying outside Canis Major. Of these, the first is now in Monoceros and the fifth in Canis Major. The remainder were used by Petrus Plancius to form a new constellation, Columba, the dove. Click here for more on Ptolemy’s ‘unformed’ stars.

Above: Eleven ‘unformed’ stars around Canis Major, as listed in the Almagest. Nine of these later became part of a new constellation, Columba. The letter M before the latitudes stands for ‘meridionalis’, Latin for ‘southern’.

A scan of the complete 1515 printing of the Almagest can be downloaded from this link. The detailed analysis of the catalogue by the astronomers C. H. F. Peters and E. B. Knobel published in 1915 can be downloaded here. Incidentally, in his Preface to the latter work, Knobel noted: ‘Notwithstanding Ptolemy’s statement that he “observed as many stars as it was possible to perceive, even to the sixth magnitude,” ... the catalogue is in all probability that of Hipparchus reduced by the addition of a constant to the longitudes’, although not all authorities agree. For some more recent thoughts on the identity of various stars in the Almagest, see Keith Pickering’s article A Re-identification of some entries in the Ancient Star Catalog (DIO , vol. 12, pp. 59–66, 2002).

The Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahmān al-Ṣūfī revised and updated the Almagest in the 10th century, but Ptolemy’s catalogue was not fully superseded until the end of the 16th century when Tycho Brahe produced a thousand-star catalogue that was ten times more accurate, heralding a new era of star surveying.

Ptolemy’s 48 constellations

Modern Latin names are given first, followed by Ptolemy’s Greek originals. The first figure after each name is the number of stars tabulated by Ptolemy, and the second figure is any ‘unformed’ stars outside the main figure. The constellations are listed in the same order as they appear in the Almagest, namely 21 north of the zodiac, the 12 constellations of the zodiac, and 15 south of the zodiac.

Ursa Minor

Ἄρκτος μικρά (Arktos mikra)

7 + 1

Cancer

Καρκίνος (Karkinos)

9 + 4

Ursa Major

Ἄρκτος μεγάλη (Arktos megale)

27 + 8

Leo

Λέων

27 + 8

Draco

Δράκων (Drakon)

31

Virgo

Παρθένος (Parthenos)

26 + 6

Cepheus

Κηφεύς

11 + 2

Libra

Χηλαί (Chelae)

8 + 9

Boötes

Βοώτης

22 + 1

Scorpius

Σκορπίος

21 + 3

Corona Borealis

Στέφανος (Stephanos)

8

Sagittarius

Τοξότης (Toxotes)

31

Hercules

Ἐνγόνασι (Engonasi)

28[a] + 1

Capricornus

Αἰγόκερως (Aigokeros)

28

Lyra

Λύρα

10

Aquarius

Ὑδροχόος (Hydrochoös)

42 + 3

Cygnus

Ὄρνις (Ornis)

17 + 2

Pisces

Ἰχθύες (Ichthyes)

34 + 4

Cassiopeia

Κασσιέπεια

13

Cetus

Κῆτος

22

Perseus

Περσεύς

26 + 3

Orion

Ὠρίων

38

Auriga

Ἡνίοχος (Heniochos)

14

Eridanus

Ποταμός (Potamos)

34

Ophiuchus

Ὀφιοῦχος

24 + 5

Lepus

Λαγωός (Lagoös)

12

Serpens

Ὄφις (Ophis)

18

Canis Major

Κύων (Kyon)

18 + 11

Sagitta

Ὀιστός (Oistos)

5

Canis Minor

Προκύων (Prokyon)

2

Aquila (+ Antinous)

Ἀετός (Aetos)

9 + 6

Argo

Ἀργώ

45

Delphinus

Δελφίν (Delphin)

10

Hydra

Ὕδρος (Hydros)

25 + 2

Equuleus

Ἵππου προτομή (Hippou protome)

4

Crater

Κρατήρ

7

Pegasus

Ἵππος (Hippos)

20

Corvus

Κόραξ (Korax)

7

Andromeda

Ἀνδρομέδα

23

Centaurus

Κένταυρος

37

Triangulum

Τρίγωνον (Trigonon)

4

Lupus

Θηρίον (Therion)

19

Aries

Κριός (Krios)

13 + 5

Ara

Θυμιατήριον (Thymiaterion)

7

Taurus

Ταῦρος

32[b] + 11

Corona Australis

Στέφανος νότιος (Stephanos notios)

13

Gemini

Δίδυμοι (Didymoi)

18 + 7

Piscis Austrinus

Ἰχθύς νότιος (Ichthys notios)

11[c] + 6

a. A 29th star was not counted as it was already included in the total for Boötes; this star is now known as Nu Boötis.

b. A 33rd star was not counted as it was already included in the total for Auriga; this star is now known as Beta Tauri.

c. A 12th star was not counted as it was already included in the total for Aquarius; this star is now known as Alpha Piscis Austrini (Fomalhaut).

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved