Genitive: Boötis

Abbreviation: Boo

Size ranking: 13th

Origin: One of the 48 Greek constellations listed by Ptolemy in the Almagest

Greek name: Βοώτης

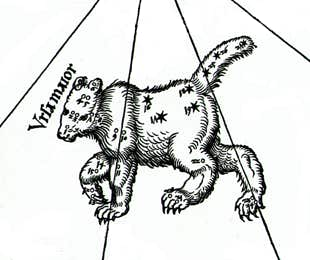

This constellation (pronounced Boh-oh-tease) is closely linked in legend with the Great Bear, Ursa Major, because of its position behind the bear’s tail. The origin of the name Boötes (Greek: Βοώτης) is not certain, but it probably comes from a Greek word meaning ‘noisy’ or ‘clamorous’, referring to the herdsman’s shouts to his animals. An alternative explanation is that the name comes from the ancient Greek meaning ‘ox-driver’, from the fact that Ursa Major was sometimes visualized as a cart pulled by oxen.

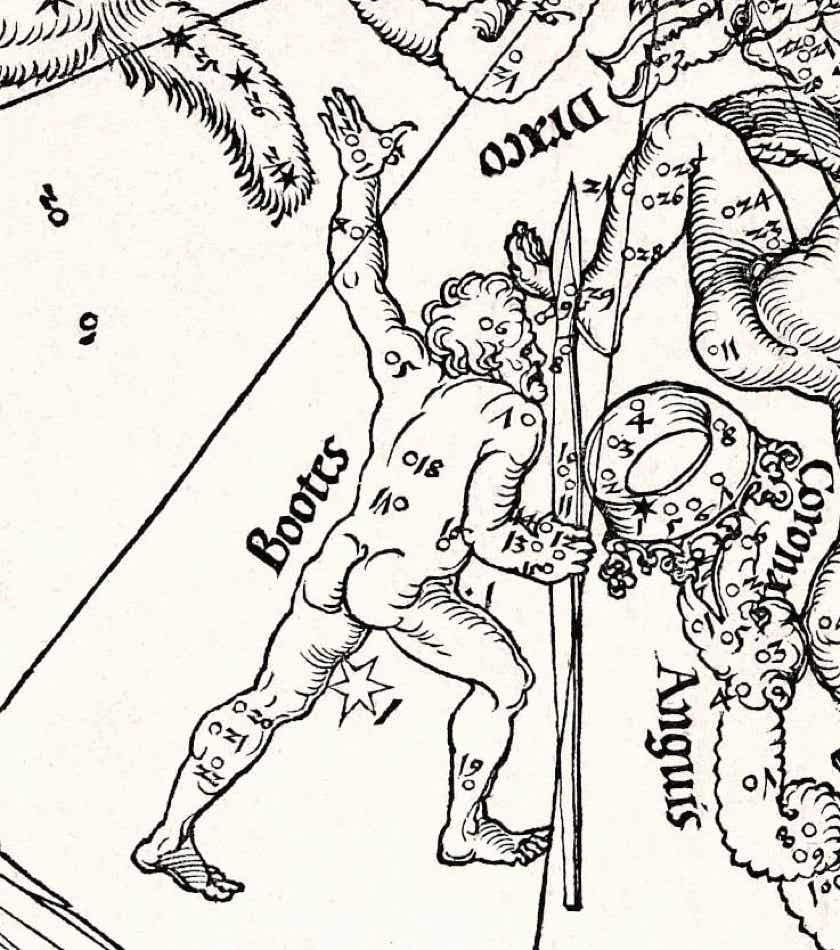

The Greeks also knew this constellation as Ἀρκτοφύλαξ (Arctophylax), variously translated as Bear Watcher, Bear Keeper, or Bear Guard. Aratus in the third century BC wrote of ‘Arctophylax, whom men also know as Boötes’, and likened him to a man driving the bear around the pole. Homer in the Odyssey some four centuries earlier called him only Boötes, which suggests it is the older name. Ptolemy evidently imagined Boötes as a herdsman, for in the Almagest he described him as carrying a κολλóροβος (kollorobos), meaning club or staff, often shown as a shepherd’s crook, as in Bode’s chart below.

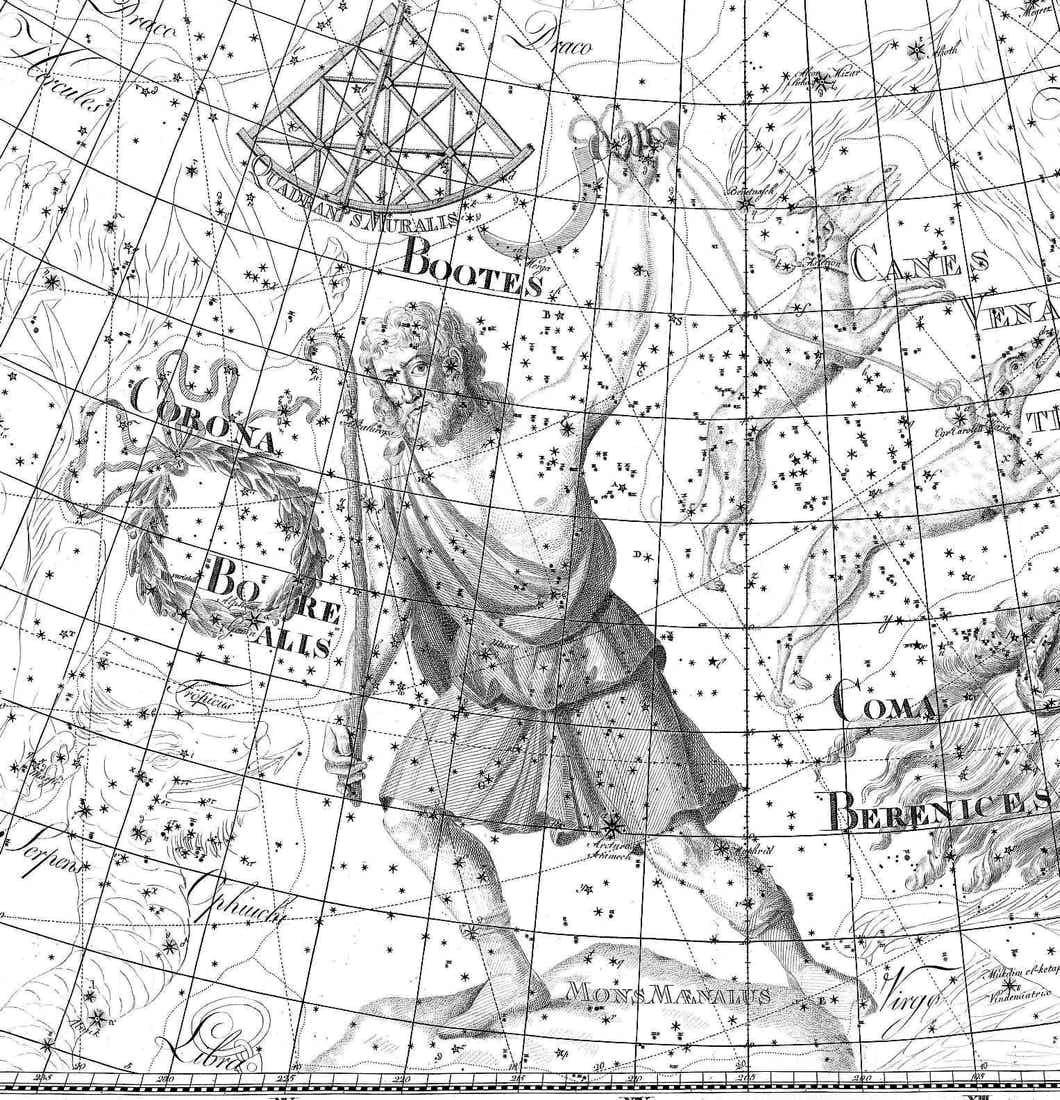

Later astronomers have given Boötes two dogs, in the form of the neighbouring constellation Canes Venatici, but they were not part of the original Greek visualization or legend.[note] The Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius introduced a sub-constellation beneath the feet of Boötes called Mons Maenalus, named after a real mountain in Arcadia, first seen on his atlas published in 1690. This was adopted by many later astronomers, including Bode, but eventually became obsolete.

Boötes on Chart VII of the Uranographia of Johann Bode (1801). In his right hand he carries a shepherd’s crook or club, and a sickle in his left with which he also grasps the leash of his hunting dogs, represented by neighbouring Canes Venatici. Ptolemy in the Almagest mentioned the club (shown in some representations as a spear, such as by Dürer) but said nothing about the sickle, which is a later addition. Here Boötes is standing on Mons Maenalus, an obsolete sub-constellation. Above his head is another obsolete constellation, Quadrans Muralis. The constellation’s brightest star, Arcturus, lies on the hem of his tunic, next to his left knee.

According to a story that goes back to Eratosthenes, the constellation represents Arcas, son of the god Zeus and his paramour Callisto, daughter of King Lycaon of Arcadia. One day Zeus came to dine with Callisto’s father King Lycaon, an unusual thing for a god to do. To test whether his guest really was the great Zeus, Lycaon cut up Arcas and served him as part of a mixed grill (some say that this deed was done not by Lycaon but by his sons). Zeus easily recognized the flesh of his own son. In a burning rage, he tipped over the table, scattering the feast, killed the sons of Lycaon with a thunderbolt, and turned Lycaon into a wolf. Then Zeus collected the parts of Arcas, made them whole again and gave his reconstituted son to Maia the Pleiad to bring up.

Arcas meets the bear

Meanwhile, Callisto had been turned into a bear, some say by Zeus’s wife Hera out of jealousy, or by Zeus himself to disguise his paramour from Hera’s revenge, or even by Artemis to punish Callisto for losing her virginity. Whatever the case, when Arcas had grown into a strapping teenager he came across this bear while hunting in the woods. Callisto recognized her son, but although she tried to greet him warmly she could only growl. Not surprisingly, Arcas failed to interpret this expression of motherly love and began to chase the bear. With Arcas in hot pursuit, Callisto fled into the temple of Zeus, a forbidden place where trespassers were punished by death. Zeus snatched up Arcas and his mother and placed them in the sky as the constellations of the bear-keeper and the bear.

A different identification

A second legend identifies Boötes with Icarius (not to be confused with Icarus, son of Daedalus). According to this tale, recounted at length by Hyginus in Poetic Astronomy, the god Dionysus taught Icarius how to cultivate vines and make wine. When he offered some of his new vintage to shepherds, they became so intoxicated that their friends thought they had been poisoned, and in revenge they killed Icarius.

His dog Maera fled home howling and led Icarius’s daughter Erigone to where his body lay beneath a tree. In despair, Erigone hanged herself from the tree; even the dog died, either of grief or by drowning itself. Zeus put Icarius into the sky as Boötes, his daughter Erigone became the constellation Virgo and the dog became Canis Minor or Canis Major (according to different authorities).

Arcturus and other stars of Boötes

Boötes contains the fourth-brightest star in the entire sky, Arcturus (Greek: Ἀρκτοῦρος), mentioned by Homer, Hesiod, Aratus, and Ptolemy. Its name means ‘bear guard’ in Greek. Aratus described it as lying beneath his belt, while Germanicus Caesar said it ‘lies where his garment is fastened by a knot’. Ptolemy placed it between the thighs, which is where mapmakers have traditionally depicted it, as in the representations by Bode (above), Bayer, and Flamsteed. Arcturus has one of the largest proper motions of all the stars in the Almagest, as a result of which it has moved about 1° south (two Moon diameters) since Ptolemy’s time, but that is not enough to disturb the overall outline of the constellation.

On Bode’s chart, above, it is given the alternative name Aramech, which comes from the Arabic al-Simāk al-rāmiḥ, meaning the Simāk with the lance or spear. The spear itself, al-rumh, was marked by nearby Eta Boötis, which lay on the left leg of Boötes in Ptolemy’s visualization. The meaning of the word Simāk has long been debated, but according to a study of Arabic star names by Danielle Adams of the University of Arizona it referred to something that was used to raise or support something else, in this case the canopy of the heavens. This makes sense because, as seen from Middle Eastern latitudes, Arcturus culminates virtually overhead, with Spica in Virgo below it. According to Adams, Arcturus and Spica were known to Arab astronomers as the two Sky Raisers (al-simākān).

The second-brightest star in the constellation is Epsilon Boötis, magnitude 2.5. Ptolemy in the Almagest said that it lay in the περίζωμα (i.e. perizoma, meaning loincloth) of Boötes. Map makers such as Bayer, Flamsteed, and Bode (above) placed it on his right hip. The star’s popular name, Izar, comes from the Arabic word izār meaning girdle or loincloth. The German astronomer Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve (1793–1864) called it Pulcherrima, Latin for most beautiful, because it is actually a close double of contrasting orange and blue when seen telescopically. (Struve is sometimes credited with discovering that Epsilon is a double, but the true discoverer was William Herschel in 1779.)

His head is marked by Beta Boötis, known as Nekkar from a misreading of the Arabic name al-baqqār, meaning the ox-driver or herdsman. Between his head and Draco lay the now-obsolete constellation Quadrans Muralis, introduced by Lalande in 1795, from which the Quadrantid meteor shower takes its name.

Chinese associations

In ancient China, Arcturus was known as Dajiao, ‘great horn’, since it marks the horn on the head of the Blue Dragon. It was also said to symbolize the throne of the celestial king, Tian wang, who was visualized as holding court in this area, although it is not clear how this character differs (if at all) from either the terrestrial Emperor or the supreme sky god. This star’s status comes about not just because it is the brightest in the northern half of the sky, but also because it lies in the first lunar mansion, Jiao, where the full Moon appeared each spring, marking the start of the year. Additionally, it is in line with the handle of the Big Dipper (or Beidou in Chinese) which was used as a seasonal clock-hand in the sky. Hence Arcturus/Dajiao became associated with the annual cycle of the seasons, a powerful symbol of cosmic harmony.

Dajiao was escorted by two aides, known as Sheti, each consisting of three stars, who were said to help determine the seasons. The Sheti to the right of Dajiao (called Yousheti) was formed by Eta, Tau and Upsilon Boötis, while the one on the left (Zuosheti) consisted of Omicron, Pi, and Zeta Boötis. Three stars to the north of Dajiao, possibly 12, 11, and 9 Boötis, formed Dixi, a mattress for the Emperor to use during banquets and receptions. In one version of the Chinese sky, the triangle of 1, 2, and 6 Boötis formed Zhouding, a three-legged bronze food container, although another version identifies Zhouding with three brighter stars in Coma Berenices.

A row of constellations running northwards from Dajiao were concerned with security. Epsilon, Sigma, and Rho Boötis formed Genghe, either a shield or a lance; Zhaoyao (Gamma Boötis) was a sword or spear; Xuange (Lambda Boötis) was a halberd; and Tianqiang (Kappa, Iota, and Theta Boötis) was a spear. Also in northern Boötes, Qigong (‘seven dukes’ or ‘seven excellencies’) extended over the border from Hercules; there are at least two different versions of Qigong, one ending at Delta Boötis and the other at Beta Boötis.

Somewhere south of Dajiao was the constellation Kangchi, representing a lake. Its location is quite uncertain and is another example of a Chinese constellation being redrawn over time. It is variously placed in Boötes, partly in Boötes and partly in Virgo, or straddling the border between Virgo and Libra.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

The Arabic star name expert Paul Kunitzsch has traced the idea of dogs in this area to an error during translation of an Arabic version of the Almagest into Latin in the 12th century. It seems that the Arabic word al-kullāb referring to the shepherd’s crook (kollorobos) carried by Böotes was misread by the translator, Gerard of Cremona, as al-kilāb, meaning dogs. See Elly Dekker, Caspar Vopel's Ventures in Sixteenth-Century Celestial Cartography, note 60.