Genitive: Canum Venaticorum

Abbreviation: CVn

Size ranking: 38th

Origin: The seven constellations of Johannes Hevelius

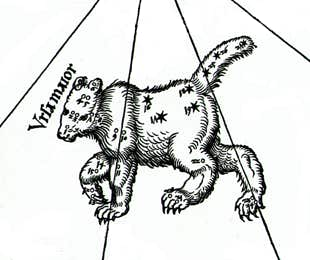

The Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius formed this constellation in 1687 from a scattering of faint stars beneath the tail of Ursa Major. Canes Venatici represents a pair of greyhounds held on a lead by Boötes, snapping at the heels of the Great Bear. Hevelius named the dogs Asterion (‘Starry’) and Chara (‘Dear’), identifying them as male and female respectively. For Hevelius’s original depiction see here.

The constellation’s two brightest stars, Alpha and Beta Canum Venaticorum, lie in the southern dog, Chara. Ptolemy had listed both these stars in the Almagest as among the ‘unformed’ stars outside the figure of the Great Bear, not belonging to any particular constellation, so they were free to be used in a new figure. Earlier in the 17th century the Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius had introduced a new constellation called Jordanus, the river Jordan, that started in this area, but Hevelius replaced it with three inventions of his own: Canes Venatici, Leo Minor, and Lynx.

Canes Venatici, a pair of hunting dogs held on a leash by Boötes, seen in the

Atlas Coelestis of John Flamsteed (1729). The dogs are greyhounds,

which hunt in pairs. Click here for the original depiction by Hevelius. Johann Bode in his Uranographia drew the dogs with their names engraved on their collars.

The idea of dogs being held by Boötes was not original to Hevelius. On a star chart published in 1533 the German astronomer Peter Apian (1495–1552) (also known as Petrus Apianus) showed Boötes with two dogs at his heels and holding their leash in his right hand. On another chart published by Apian three years later the number of dogs had grown to three and the leash had moved to the left hand, but they were still following Boötes and not the bear. (This chart was reissued with hand colouring in Apian's book Astronomicum Caesareum of 1540.) In neither case was any attempt made to connect the dogs with charted stars, nor were they named.

However, in 1602 the Dutch cartographer Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571–1638) produced a globe in which Boötes holds two dogs that are following the Great Bear. They face the same way as the modern hunting dogs although they occupy only the space filled by Hevelius’s southern dog, Chara. This was the first attempt to incorporate the two brightest stars in this area into a pair of dogs, so it would seem that Blaeu deserves at least a share of the credit for the invention of Canes Venatici.

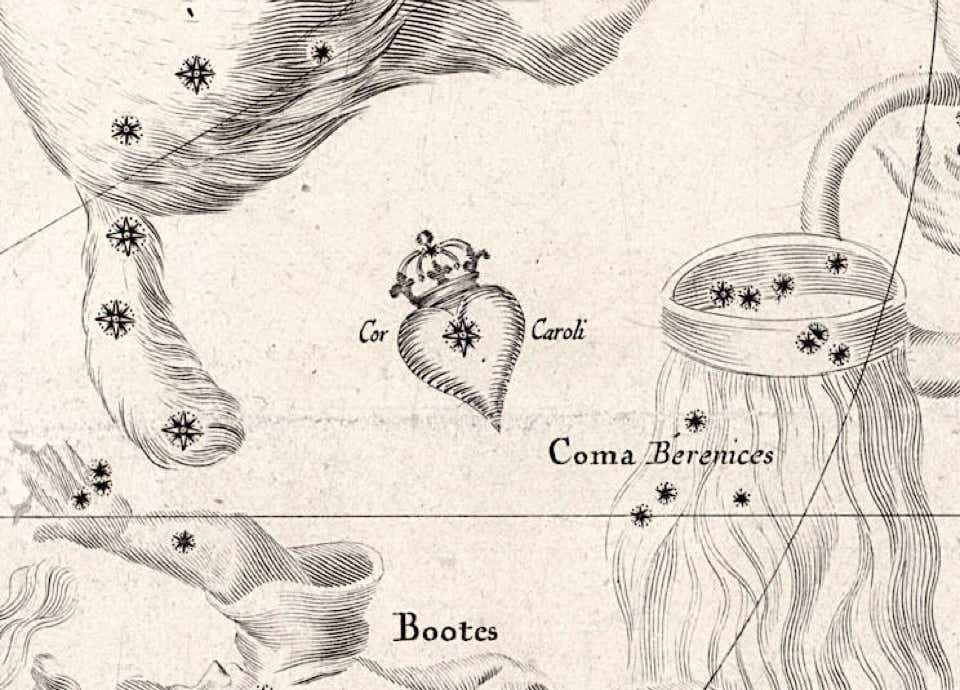

Cor Caroli, a star named for a king…

In the modern constellation, the ring attaching the southern dog’s lead to its collar is marked by the star Alpha Canum Venaticorum, popularly known as Cor Caroli, meaning Charles’s Heart, in honour of King Charles I of England who was beheaded by parliamentarians in 1649. This name arose over a decade before Canes Venatici was formed. The writer and ardent royalist Edward Sherburne tells us in his translation of Manilius published in 1675 that the name was given by Sir Charles Scarborough (1615–94), physician to King Charles I’s son, Charles II. Why Scarborough chose to name this particular star was not explained — perhaps it was because it lies close to the Plough, which was popularly known in England as Charles’s Wain, or wagon.

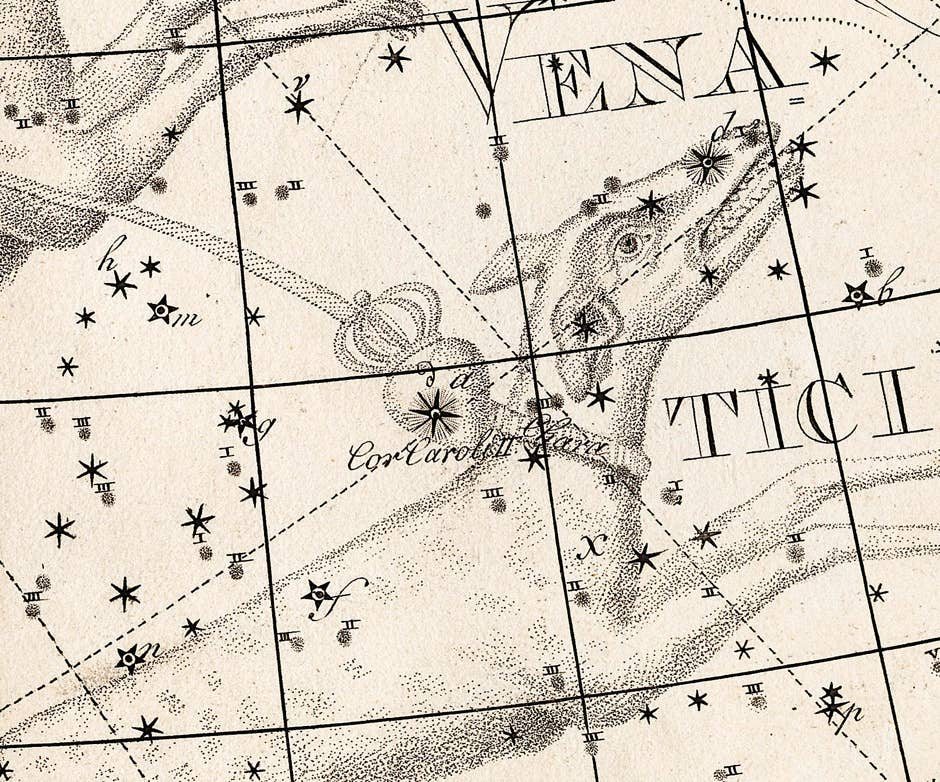

The name first appeared in 1673 on the northern half of a pair of celestial hemispheres that accompanied a book called Astroscopium by the English cartographer Francis Lamb. He labelled the star Cor Caroli Regis Martyris, a reference to the fact that King Charles I was beheaded, or ‘martyred’, as Lamb loyally put it (Charles had declared himself ‘martyr of the people’ at his execution). Lamb and others, such as Edward Sherburne in his translation of Manilius in 1675, John Seller in his Atlas Caelestis of 1677, and Seller again on a reprint of Edmond Halley’s chart of 1678 (below), drew a heart around the star surmounted by a crown, turning it into a mini-constellation that neatly filled the gap between Ursa Major, Boötes, and Coma Berenices.

Cor Caroli on a reprint of Edmond Halley’s northern hemisphere chart of 1678, issued

by the London map-maker John Seller (the first edition of the chart does not show

it). The star lies at the centre of a mini-constellation depicting a heart surmounted

by a crown. Ursa Major is above left, Coma Berenices to the right, and Boötes below.

This chart was a companion to Halley’s southern hemisphere chart, compiled after

his return from observing the southern skies on St Helena.

...but which king?

Unfortunately in 1844 the English astronomer William Henry Smyth started a long-running confusion when he wrote in his Bedford Catalogue that the star had been named by Edmond Halley after King Charles II, a mistake originally due to Bode in his star catalogue of 1801. According to Smyth’s account, Scarborough supposedly saw the then-unnamed star shining particularly brightly on the night of 1660 May 29, coincidentally when Charles II returned to London at the Restoration of the Monarchy. Smyth gave no source for this statement, and in reality such a brightening would be extremely unlikely, so the story can only be apocryphal.

Despite this, the American historian R. H. Allen unquestioningly repeated Smyth’s tall story in his classic book Star Names and it has been widely requoted. As a result there has been much uncertainty over which King Charles the star is supposed to commemorate, but Sherburne made clear that it referred to the first King Charles. (Charles II was later commemorated by Halley’s southern constellation Robur Carolinum of 1678, although that invention did not last.)

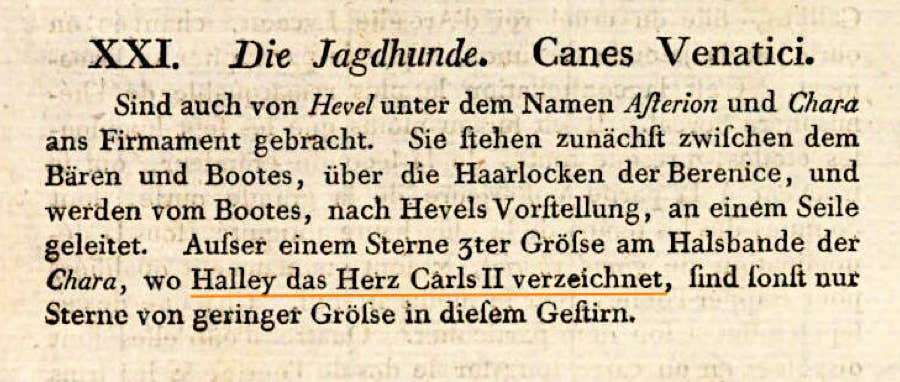

When Hevelius introduced Canes Venatici in 1687 he incorporated this star into his new constellation, but without a name or the surrounding heart. Johann Bode, in his Uranographia atlas of 1801, retained the heart and crown on the collar of the southern dog, but erred by calling the star Cor Caroli II, wrongly thinking it referred to the second King Charles. Despite its overtly nationalistic nature, the name has stuck.

Other stars, and a Whirlpool

Beta Canum Venaticorum, on the southern dog’s head, is called Chara, the same as the dog itself. The first person to apply the name Chara to this star seems to have been R. H. Allen in his book Star Names of 1899, and it is now officially accepted by the IAU. The star name expert Paul Kunitzsch said that Chara meant ‘joy’ in Greek. But Hevelius wrote in Latin, describing the dog as ‘grata et chara’, which can be translated as ‘pleasing and dear (or beloved)’. The northern dog, which Hevelius called Asterion (‘starry’, or perhaps ‘little star’), is marked only by a scattering of faint stars.

Alpha and Beta CVn are the only two stars in the constellation with Greek letters; they were given these identifiers by the English astronomer Francis Baily in his British Association Catalogue of 1845.

Another notable star in Canes Venatici is the 5th-magnitude red giant variable Y Canum Venaticorum, one of the reddest stars known. In 1868 the pioneering Italian spectroscopist Angelo Secchi (1818–78) described its spectrum as ’superba’. In 1876 the Irish astronomer John Birmingham (1816–84) took this description and turned it into the name La Superba, which is now the official name for this star.

Spiral structure of M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, drawn in March 1848 by William Parsons,

third Earl of Rosse, from a series of observations made through his 72-inch (1.8-m)

reflector at Birr Castle in Ireland. This sketch was published in 1850 in Philosophical

Transactions of the Royal Society. The spiral structure had originally been detected by

Rosse through the same telescope in April 1845.

Canes Venatici contains a beautiful spiral galaxy, M51, popularly called the Whirlpool. M51 was the first galaxy in which spiral form was noticed, by the Irish astronomer Lord Rosse (1800–67) in 1845 through his 72-inch (1.8-m) reflector at Birr Castle in Ireland. Rosse made an initial drawing of M51 in 1845 April but never published it.[note] A second version, a composite of observations at Birr, was published in 1850 (above). M51 is now known to consist of a large galaxy in near-collision with a smaller one, and lies around 25 million light years away.

Chinese associations

The stars 21 and 24 Canum Venaticorum plus a fainter, unnumbered star were known to the Chinese as Sangong, ‘three excellencies’, representing the Emperor’s closest and most trusted aides. Changchen was a group of seven stars representing a contingent of palace guards, stretching from Alpha via Beta CVn and ending just across the border at 67 Ursae Majoris.

One individual star was named Xiang, ‘prime minister’. It is usually identified as 5 Canum Venaticorum, although Sun and Kistemaker think it is not in Canes Venatici at all but is actually the star Chi Ursae Majoris.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

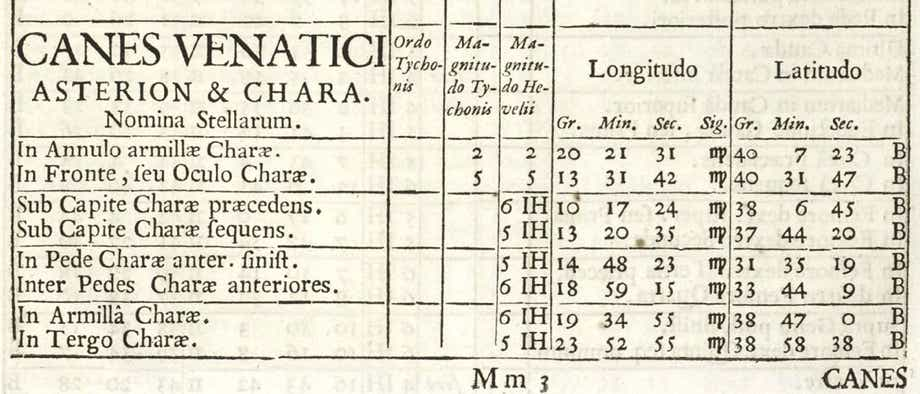

Asterion and Chara are named individually under the heading Canes Venatici in Johannes Hevelius’s Catalogus Stellarum Fixarum.

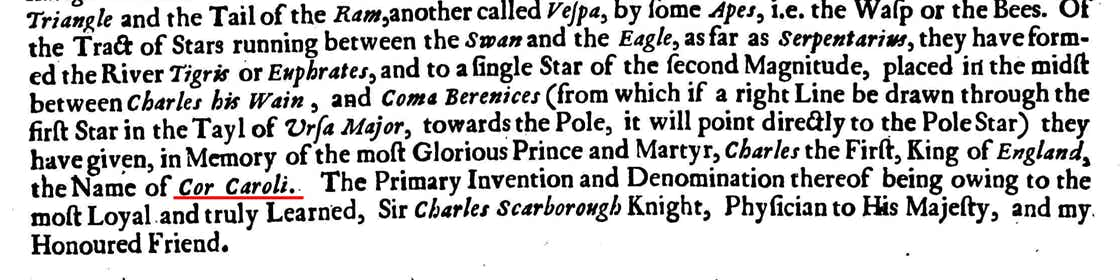

Edward Sherburne explains the origin of the name Cor Caroli in his translation of The Sphere of Marcus Manilius published in 1675.

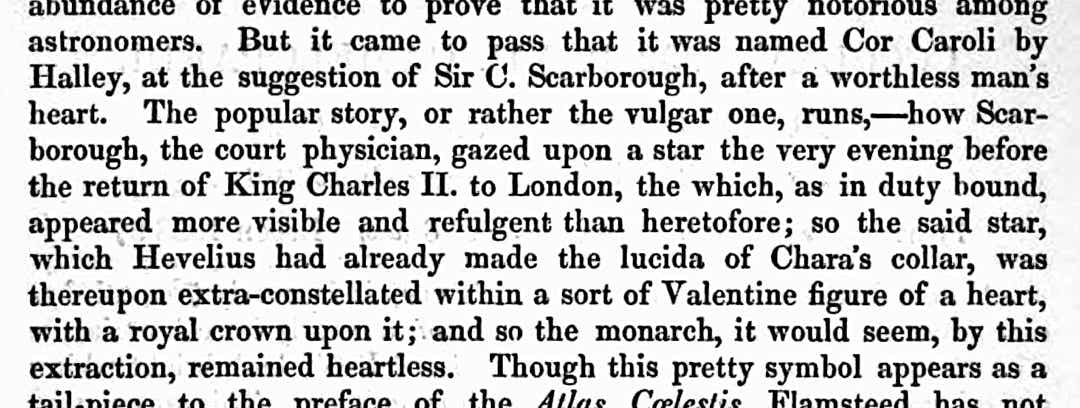

W. H. Smyth’s fanciful explanation of the origin of the name Cor Caroli in his Bedford Catalogue of 1844 started a long-running myth.

Cor Caroli, labelled Cor Caroli II, lies within a heart and crown on the collar of the southern dog, Chara, as seen on Chart VII of Johann Bode’s Uranographia. The dog’s name is engraved on its collar.

A copy of Rosse’s initial drawing was published in 1846 in a book called Thoughts on Some Important Points Relating to the System of the World by the Scottish astronomer and author John Pringle Nichol (1804–59), who observed with Rosse at Birr and helped publicize his discoveries. In the engraving published in his book, white and black are reversed to give white stars on a black background. This version of the sketch has often been reproduced, but it is an artist’s copy and not Rosse’s original. Pringle referred to M51 not as the Whirlpool but as the Scroll nebula.