How Ptolemy’s spare stars became new constellations

Ptolemy’s great synthesis of Greek astronomy called the Almagest, written around AD 150, contained a catalogue of just over 1,000 stars divided into 48 constellations which were the foundation of our modern constellation system. Of these stars, 108 (i.e. slightly more than 10%) were classified by Ptolemy as ‘unformed’, meaning they did not belong to any of the recognized figures. They literally were left-overs.

Most of these stars were eventually merged with the nearest existing constellation by later astronomers, but some were incorporated into new constellations, as described below.

1. Stars around Ursa Major

Unlike modern star catalogues, in which stars are tabulated in order of right ascension, Ptolemy grouped his stars on a constellation-by-constellation basis, from Ursa Minor in the north to Piscis Austrinus in the south. In some constellations the main table of constituent stars was followed by a subsidiary list of stars that Ptolemy considered to be ‘outside’ the main constellation figure; he called them ἀμόρφωτοι (amorphotoi), i.e. ‘unformed’ stars (informatae in Latin). In those days constellations were regarded literally as pictures in the sky, rather than specifically defined areas as we know them today, and the ‘unformed’ stars did not fit the imaginary constellation figures, or at least not as Ptolemy visualized them.[note]

In the case of Ursa Major Ptolemy listed eight such ‘unformed’ stars. They are given in Table 1 with Ptolemy’s descriptions of their locations as well as their modern identifications.

These eight stars can be seen, for example, on Albrecht Dürer’s northern celestial chart from 1515 which was compiled from Ptolemy’s star catalogue (Figure 1). What became of them?

In his introduction to his star catalogue, Ptolemy wrote: ‘The descriptions which we have applied to the individual stars as parts of the constellation are not in every case the same as those of our predecessors … in many cases our descriptions are different because they seem to be more natural and to give a better proportioned outline to the figures described.’ Ptolemy’s quote emphasizes how dependent the early constellations were on human imagination.

Table 1:

Stars listed by Ptolemy as lying outside Ursa Major

Ptolemy’s description

Identification

1. The star under the tail, at some distance towards the south

α CVn

2. The rather faint star in advance of it

β CVn

3. The southernmost of the [two] stars between the front legs of Ursa [Major] and the head of Leo

α Lyn

4. The one north of it

38 Lyn

5. The rearmost of the remaining three faint stars

10 UMa?

6. The one in advance of this

35 Lyn?

7. The one in advance again of the latter

34 Lyn?

8. The star between the front legs [of Ursa Major] and Gemini

31 Lyn

The descriptions in English are taken from G. J. Toomer’s translation of the Almagest (Princeton University Press, 1998).

Figure 1 : Eight ‘unformed’ stars that were catalogued by Ptolemy around Ursa Major are seen here on Albrecht Dürer’s northern celestial hemisphere chart of 1515. Dürer numbered these stars from 1 to 8, the order in which they were listed in the Almagest. Stars 1 and 2, under the tail of the bear, at upper right of this illustration, were the basis of Johannes Hevelius’s new constellation Canes Venatici. The other six were incorporated by Hevelius into Lynx. Dürer’s chart shows the constellations back to front, as they would appear on a celestial globe. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

1.1. Jordanus

First to find a home for them was the Dutch cartographer Petrus Plancius (1552–1622). On a celestial globe of 1612 he introduced a new constellation which he called Jordanus, the river Jordan. This river rose under the tail of the Great Bear, in the area of Ptolemy’s unformed stars 1 and 2, ran under the Bear’s feet via stars 3 to 8, and ended next to Camelopardalis, another Plancius invention. Jordanus made its first appearance in print on the charts of the German astronomer Jacob Bartsch (c.1600–33) in his book Usus Astronomicus Planisphaerii Stellati of 1624, as a result of which Bartsch was sometimes erroneously credited with its invention.

1.2. Canes Venatici

Jordanus flowed across the northern sky for most of the 17th century until it was supplanted by not one but three new constellations, all from the same author. Shortly before his death in 1687 the Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius (1611–87) completed a catalogue of 1,564 stars called Catalogus Stellarum Fixarum in which he introduced ten new constellations, seven of which are still recognized today. The catalogue and its accompanying atlas, Firmamentum Sobiescianum, were published posthumously in 1690.

With an admirable exercise of imagination, Hevelius transformed the area under the tail of Ursa Major into a pair of greyhounds held on a lead by Boötes, snapping at the heels of the Great Bear. He named this new constellation Canes Venatici, the hunting dogs. Ptolemy’s stars 1 and 2 in Table 1 both lie in the southern dog. We now know them as Alpha and Beta Canum Venaticorum, the Greek letters having been assigned to them by the English astronomer Francis Baily in his British Association Catalogue of 1845.

1.3. Lynx

Hevelius insisted on measuring star positions with the naked eye even though he possessed telescopes for observing the Moon and planets. Many of his constellations were deliberately faint as though he was boasting of the power of his eyesight, nowhere more so than in Lynx. Hevelius wrote that anyone who wanted to observe it would need the eyesight of a lynx (‘oculos habeat Lynceos’), although he undoubtedly exaggerated the faintness of the 19 stars he catalogued in it. Lynx supposedly represents the tufty-eared, medium-sized member of the cat family of the same name, but the animal shown on Hevelius’s chart of the constellation does not look much like it.

Six of its stars, all in the rear part of the constellation, had been listed by Ptolemy as lying outside Ursa Major, south of the bear’s forepaws; these are numbered 3 to 8 in Table 1 and on Dürer’s chart in Figure 1. Star 3 is the present-day Alpha Lyncis, star 4 is 38 Lyncis, and star 8 is 31 Lyncis. The identity of the other three stars is uncertain, but according to one study they could be the present-day 10 Ursae Majoris, 35 Lyncis, and 34 Lyncis all misplaced by ten degrees in Ptolemy’s catalogue.

2. A hair-raising story

Ptolemy’s catalogue listed eight unformed stars in the area around Leo. The first of these was used by Hevelius in his new constellation Leo Minor (where it is now known as 41 LMi), and the next four have since been merged into the modern Leo. But the last three stars (numbers 6, 7, and 8) have a more interesting story, as they were the basis for the constellation Coma Berenices. They are listed in Table 2 with Ptolemy’s descriptions and they can be seen on Dürer's northern hemisphere star chart of 1515 (Figure 2).

Table 2:

Unformed stars 6, 7, and 8 outside Leo

Ptolemy’s description

Identification

6. The northernmost part of the nebulous mass between the edges of Leo and Ursa [Major], called Coma [note]

γ Com

7. The most advanced of the southern outrunners of Coma

7 Com

23 Com

The descriptions in English are taken from G. J. Toomer’s translation of the Almagest (Princeton University Press, 1998).

The use of the name Coma is Toomer’s. Ptolemy actually used the Greek word Πλόκαμος – Plokamos in Latin transliteration – meaning lock, tress, or braid.

Figure 2 : The triangle of stars surrounding what Ptolemy called the ‘nebulous mass’ above the tail of Leo, as seen on Albrecht Dürer’s northern celestial chart of 1515. Dürer has numbered them 6, 7, and 8, as they are the 6th, 7th and 8th of the ‘unformed’ stars Ptolemy listed as lying outside Leo. This area is now filled by Coma Berenices. The two stars farther north, under the hind quarters of Ursa Major, formed the basis for Hevelius’s Canes Venatici (Section 1.2). (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The ‘nebulous mass’ referred to by Ptolemy in the description of star 6 is the scattered cluster we know as Melotte 111, and the three unformed stars mark its corners; they are now designated Gamma, 7, and 23 Comae Berenices. The mythologists regarded this hazy area as the hair of the real-life Queen Berenice of Egypt who married the pharaoh Ptolemy III Euergetes in 246 BC.

According to the story, Berenice cut off her hair in gratitude to the gods for the safe return of her husband from the Third Syrian War the following year. She placed the locks in the temple of Arsinoë, but they vanished overnight. The astronomer Conon of Samos (c.280–c.220 BC) pointed out the hazy patch near the tail of the lion, telling Berenice that her hair had been transported from the temple to the sky.

Although the story of Berenice’s hair was well-known in Ptolemy’s time, 400 years after the supposed event, this area was still not regarded as a separate constellation. It remained that way until 1536 when the German mathematician and cartographer Caspar Vopel (1511–61) showed Berenice’s flowing locks for the first time on a celestial globe under the name Berenices Crinis (Figure 3).

Figure 3 : Queen Berenice is engulfed by her flowing locks on Caspar Vopel’s globe of 1536. She sits within a triangle of stars, numbered 6, 7, and 8, that Ptolemy had described as lying outside Leo, also seen on Figure 2. This was the first-ever visualization of this constellation. (Cologne City Museum.)

Vopel was followed by the Dutch cartographer Gerardus Mercator (1512–94) who named the new constellation Cincinnus, a Latin word meaning lock of hair, on a globe he made in 1551. Tycho Brahe included it under the name Coma Berenices in his star catalogue of 1602, which ensured its widespread adoption. The constellation as envisaged by Vopel, Mercator, and Tycho covers a much larger area than the nebulous mass described by Ptolemy, as does the modern-day version.

3. Noah’s dove

Among the earliest of those who added to the 48 constellations of Ptolemy was the Dutch theologian and cartographer Petrus Plancius (1552–1622). He is credited with having invented Columba, Camelopardalis, and Monoceros, all three of which we still recognize today, as well as several other constellations such as Jordanus which are now obsolete.

Camelopardalis and Monoceros filled areas in the Greek sky that were devoid of stars in the Almagest, while Columba utilized nine out of eleven unformed stars that Ptolemy had listed as lying outside Canis Major (Table 3). These unformed stars can be seen, for example, on the southern half of Albrecht Dürer’s star chart of 1515 as two little groups, one to the south of Lepus and the other between the hind legs of Canis Major (Figure 4). Of the two stars in this Table that did not become part of Columba, star 1 is probably the present-day 22 Monocerotis (the only Ptolemaic star in Monoceros) while star 5 is Lambda Canis Majoris.

Table 3:

Unformed stars outside Canis Major

Ptolemy’s description

Identification

1. The star to the north of the top of Canis [Major]

22 Mon

2. The southernmost of the four stars almost on a straight line under the hind legs

θ Col

3. The one north of this

κ Col

4. The one north again of this

δ Col

5. The last and northernmost of the four

λ CMa

6. The most advanced of the three stars almost on a straight line to the west of the four

μ Col

λ Col

7. The middle one

γ Col

8. The rearmost of the three

β Col

9. The rearmost of the two bright stars under these

10. The more advanced of them

α Col

11. The last star, to the south of the above

ε Col

The descriptions in English are taken from G. J. Toomer’s translation of the Almagest (Princeton University Press, 1998).

Figure 4 : Ptolemy listed 11 unformed stars around Canis Major. The first of these can be seen above the head of Canis Major, at the top of this illustration from Albrecht Dürer’s northern celestial chart of 1515. This star is now part of Monoceros, a constellation invented in 1612 by Petrus Plancius. The other 10 stars lay to the south of Lepus and Canis Major. Dürer numbered them from 2 to 11, the order in which they were listed in the Almagest (this illustration has been turned so that north is at the top, and the numbers are upside-down). Petrus Plancius used these ‘spare’ stars to form Columba, the dove, in 1592. The stern of Argo Navis is at lower right. Dürer’s chart showed the constellations in mirror image, as they would appear on a celestial globe. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Columba is supposed to represent Noah’s dove, sent out from the Ark to find dry land. It returned with an olive branch in its beak, a sign that the Biblical Flood was at last subsiding. The dove made a modest debut in 1592, when it appeared on a celestial hemisphere that Plancius tucked into one corner of his first great terrestrial map. Columba was introduced to a wider audience by Johann Bayer when he included it as part of the chart of Canis Major in his Uranometria atlas of 1603.

4. King Poniatowski’s bull

Just above the right shoulder of Ophiuchus and the tail of Serpens lies a V-shaped group of five stars that Ptolemy classed as unformed (Table 4). They can be seen in Figure 5 as they appeared on Albrecht Dürer’s northern celestial chart from 1515.

Table 4:

Unformed stars outside Ophiuchus

Ptolemy’s description

Identification

1. The northernmost of the three to the east of the right shoulder

66 Oph

2. The middle one of the three

67 Oph

3. The southernmost of them

68 Oph

4. The star to the rear of these three, approximately over the middle one

70 Oph

5. The lone star north of [these] four

72 Oph

The descriptions in English are taken from G. J. Toomer’s translation of the Almagest (Princeton University Press, 1998).

Figure 5 : Five stars above the shoulder of Ophiuchus, seen on Albrecht Dürer’s northern celestial chart of 1515, formed the basis of the now-extinct constellation Taurus Poniatovii, created by Martin Poczobut to honour King Poniatowski. The stars are numbered from 1 to 5, the order in which they were listed in the Almagest. On this chart the constellations are reversed left to right as on a globe, so Ophiuchus is seen from behind. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Lithuanian astronomer Martin Poczobut (1728–1810), director of the Royal Observatory at Vilna (now Vilnius), thought them reminiscent of the Hyades cluster that outlines the face of Taurus. Sensing an opportunity to impress, he used them as the basis for a new constellation, Poniatowski’s bull, to honour King Stanisław August Poniatowski, who was monarch of both Poland and Lithuania and whose coat of arms included a bull. In 1777 Poczobut privately published a list of 16 component stars which Johann Bode reprinted for wider circulation five years later in his Astronomisches Jahrbuch.

Poczobut used four of Ptolemy’s stars to make up the face of the little bull, while the fifth and brightest, which we now know as 72 Ophiuchi, lay on the bull’s right horn. The little bull was first depicted in 1778 as le Taureau Royal de Poniatowski in a revised edition of Jean Fortin’s Atlas Céleste. Bode later Latinized its name to Taurus Poniatovii on his Uranographia atlas of 1801. However, as with all such attempts to confer celestial honours on royal patrons, King Poniatowski’s bull did not last long in the sky before being put out to pasture and its stars are now officially part of Ophiuchus and Serpens Cauda.

5. The Emperor’s boyfriend

In addition to the standard 48 constellations in the Almagest, a 49th was also mentioned by Ptolemy, although only as a subdivision of Aquila. It was called Antinous, and it appeared as a separate figure on celestial charts from the 16th to 19th centuries but never made it into the IAU’s final 88.

Antinous was a real person, although the story reads like fiction. He was born c. AD 110 at Bythinium in Roman-occupied Turkey where he caught the eye of Hadrian, the first openly gay Roman emperor, during an official visit. From then on he became the emperor’s constant companion.

However, Hadrian’s happiness did not last long. While on a trip up the Nile in AD 130, Antinous drowned near the present-day town of Mallawi in Egypt. Whether the drowning was accident, suicide, or even ritual sacrifice we do not know; but, whatever the case, Hadrian was heartbroken by the loss. He founded a city called Antinoöpolis near the site of the drowning, declared Antinous a god, and commemorated him in the sky as a new constellation.

According to Ptolemy, Antinous consisted of six stars south of Aquila of 3rd to 5th magnitude (Table 5). These can be seen, for example, on Albrecht Dürer’s star chart of 1515 (Figure 6). Ptolemy worked at Alexandria at the mouth of the Nile and he compiled the Almagest only about 20 years after the famous drowning so he would have known the story; indeed, he might have had a hand in creating the constellation, possibly at Hadrian’s request.

Table 5:

Stars around Aquila ‘to which the name Antinous is given’

Ptolemy’s description

Identification

1. The more advanced of the two stars south of the head of Aquila

η Aql

2. The rearmost of them

θ Aql

3. The star to the south and west of the right shoulder of Aquila

δ Aql

4. The one to the south of this

ι Aql

5. The one to the south again

κ Aql

6. The star most in advance of all

λ Aql

The descriptions in English are taken from G. J. Toomer’s translation of the Almagest (Princeton University Press, 1998).

Figure 6 : Ptolemy listed six stars lying outside Aquila, ‘to which the name Antinous is given’, as he wrote. Here they are seen on Albrecht Dürer’s northern celestial hemisphere chart of 1515, numbered from 1 to 6 in the order in which they appeared in the Almagest. Antinous was visualized in the sky for the first time on Caspar Vopel’s globe of 1536 (Figure 7). Dürer’s chart was also drawn in globe view, so the constellations appear reversed. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The constellation’s first known depiction was in 1536 on the same celestial globe by Caspar Vopel as Berenices Crinis made its debut (Figure 7). Gerardus Mercator also showed it on a globe of his own in 1551. Tycho Brahe listed Antinous as a separate constellation in his star catalogue of 1602 and it remained widely accepted into the 19th century, but its stars were eventually remerged with Aquila.

Figure 7 : Antinous kneels on a pedestal with arms outstretched beneath Aquila the eagle, as depicted on Caspar Vopel’s celestial globe of 1536. (Cologne City Museum.)

6. Under the microscope

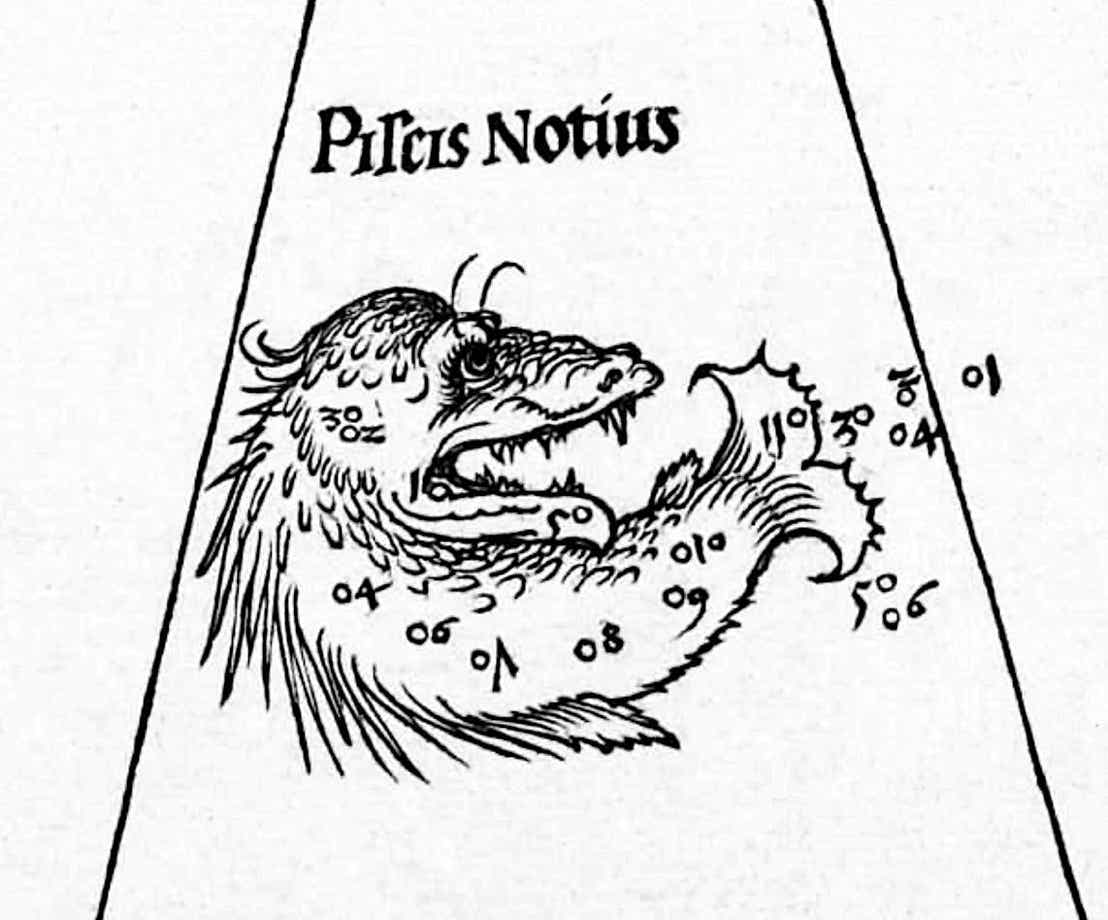

The final constellation in the Almagest was the one we know as Piscis Austrinus, which Ptolemy called Ichthys Notios. An alternative Latin name used by many astronomers into the 19th century was Piscis Notius, which is what Dürer called it on his chart of 1515. Ptolemy listed six unformed stars around the tail of the fish (Table 6), in an area which is now part of Lacaille’s constellation Microscopium. They can be seen on Dürer’s southern celestial hemisphere of 1515, but because Ptolemy’s coordinates were very inaccurate in this far-southern area it is difficult to be sure exactly which stars they were.

The identifications given in Table 6 are from Toomer’s translation of the Almagest, but they are all highly doubtful. The historians C. H. F. Peters and E. B. Knobel in their Revision of the Almagest (1915) identified the first three stars as Alpha, Gamma, and Epsilon Microscopii, which seems likely as these are the three brightest stars in this area. Star 4 is possibly HR 8076, but stars 5 and 6 cannot be identified with any certainty. The Persian astronomer al-Ṣūfī did not include any of these six unformed stars in his revision of the Almagest, presumably because he could not identify them.

Table 6:

Unformed stars around Piscis Austrinus

Ptolemy’s description

Identification

1. The most advanced of the 3 bright stars in advance of Piscis [Austrinus]

η Mic (?)

2. The middle one

θ1 Mic (?)

3. The rearmost of the three

ξ Mic (?)

4. The faint star in advance of this

θ2 Mic (?)

5. The southernmost of the remaining 2 stars to the north

γ Mic (?)

6. The northernmost of them

α Mic (?)

The descriptions in English and star identifications are taken from G. J. Toomer’s translation of the Almagest (Princeton University Press, 1998).

Figure 8: Ptolemy’s six ‘unformed’ stars outside Piscis Austrinus, numbered from 1 to 6 in the order they were listed in the Almagest, seen on the southern half of Albrecht Dürer’s celestial chart of 1515. They are now part of Microscopium. Piscis Austrinus (here called Piscis Notius) is drawn in reverse, as on a celestial globe, and south is at the top. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

Author’s note: This page is based on a paper of mine published in the Bulletin of the Society for the History of Astronomy (Issue 38, Autumn 2022).