Genitive: Doradus

Abbreviation: Dor

Size ranking: 72nd

Origin: The 12 southern constellations of Keyser and de Houtman

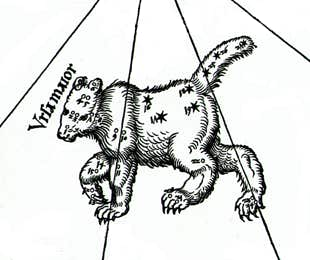

A small southern constellation introduced at the end of the 16th century by the Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. Dorado was first depicted on a star globe of 1598 by the Dutchman Petrus Plancius and first appeared in print in 1603 on the Uranometria atlas of Johann Bayer.

The constellation represents the colourful dolphinfish Coryphaena hippurus (also known as mahi-mahi) found in tropical waters, not the goldfish commonly found in ponds and aquaria. Dutch explorers observed these large predatory fish chasing flying fish and so Dorado was placed in the sky following the constellation of the flying fish, Volans, as shown on Bayer’s southern hemisphere chart.

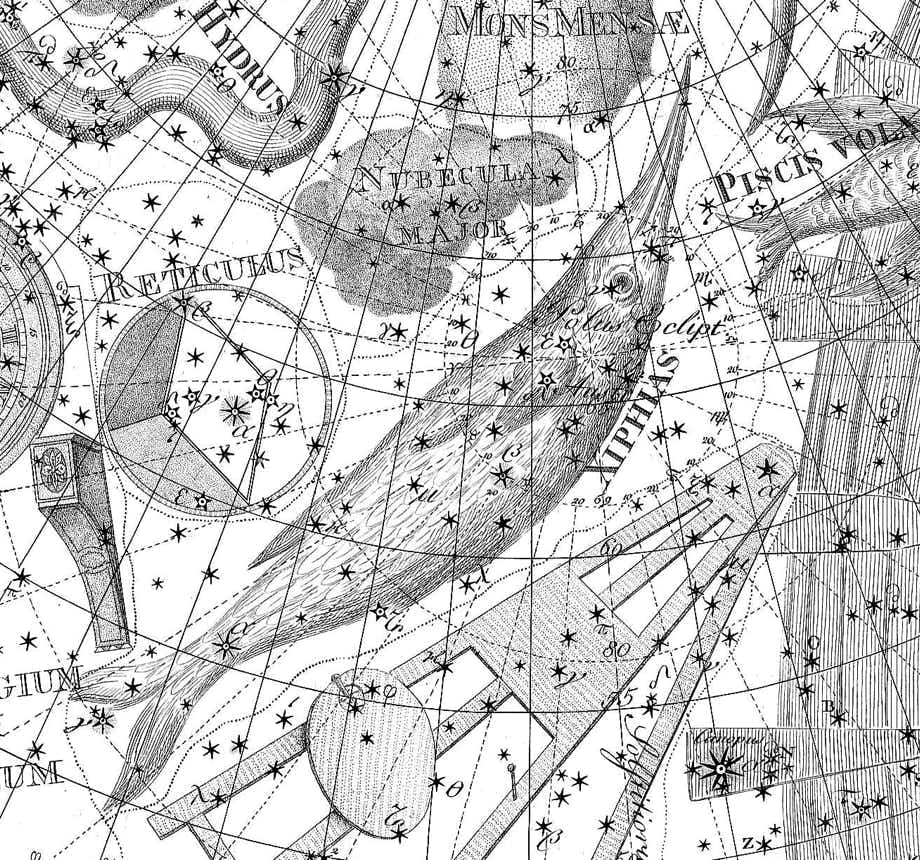

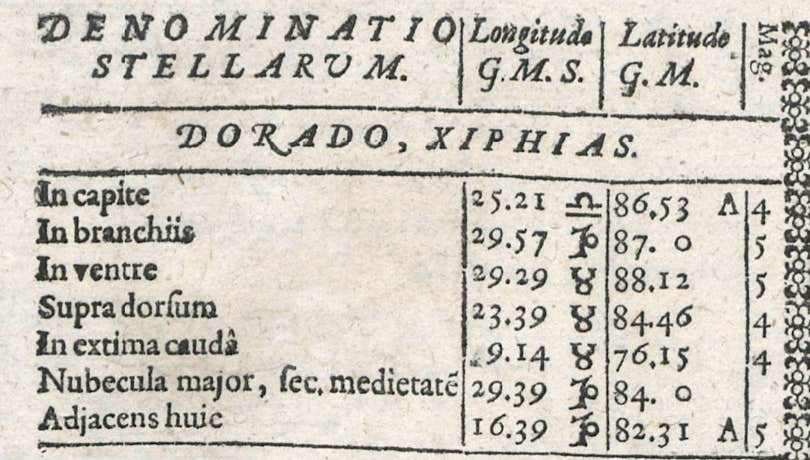

The constellation has also been known as Xiphias, the Swordfish, a name that first appeared as an alternative to Dorado in the Rudolphine Tables of Johannes Kepler published in 1627. The name Xiphias was adopted by Edmond Halley on his chart of the southern constellations in 1678, followed by Johannes Hevelius in 1690. Johann Bode also called it Xiphias on his Uranographia star atlas of 1801, as illustrated here. However, Lacaille had used the original name Dorado on his southern planisphere of 1756 and this was the version that was eventually adopted.

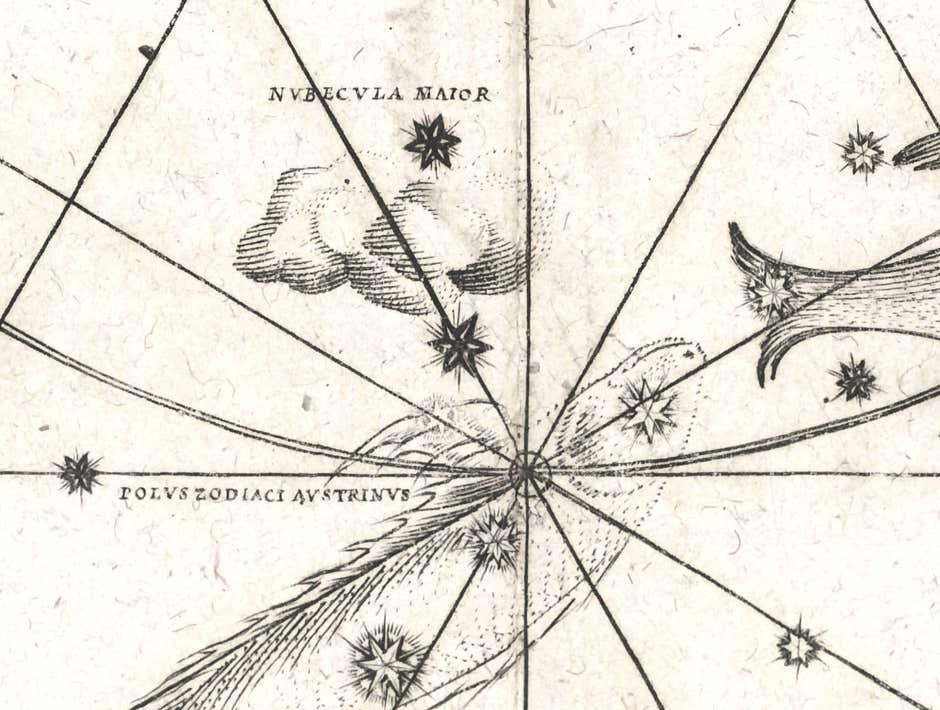

Dorado shown on Chart XX of the Uranographia of Johann Bode (1801) under the name of Xiphias, the swordfish. Nubecula Major, above it, is better known as the Large Magellanic Cloud.

Large Magellanic Cloud and 30 Doradus

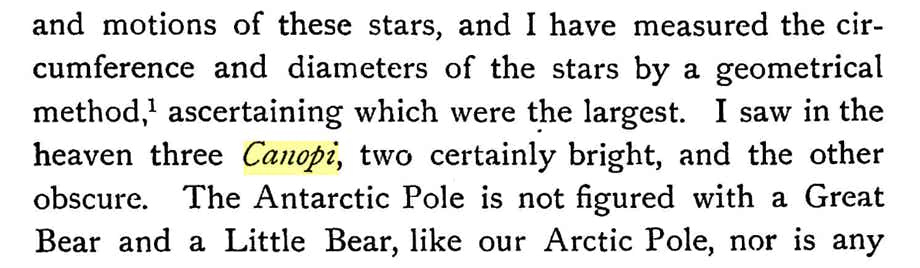

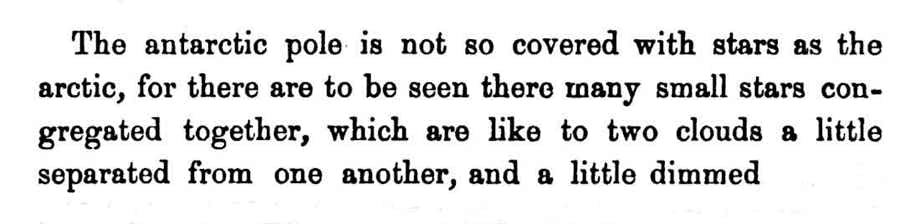

Dorado’s main claim to fame is that it contains most of the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small neighbour galaxy of our own Milky Way, about 170,000 light years away. This, like the Small Magellanic Cloud in Tucana, was first described by the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512) in an account written in 1502 in which he reported seeing three ‘canopi’, two bright, the third dark. This was evidently a sighting not only of the Magellanic Clouds but also the Coalsack Nebula which lies on the opposite side of the celestial pole from them in Crux. Another Italian explorer, Antonio Pigafetta (c.1491–c.1531), who sailed with Ferdinand Magellan on the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1519–22, wrote of ‘two clouds, a little separated from one another, and a little dimmed’. They eventually became known as the Magellanic Clouds, although they were still known by the generic term nubeculae, Latin for clouds, on the Uranographia atlas of Johann Bode as late as 1801, as on the illustration above.

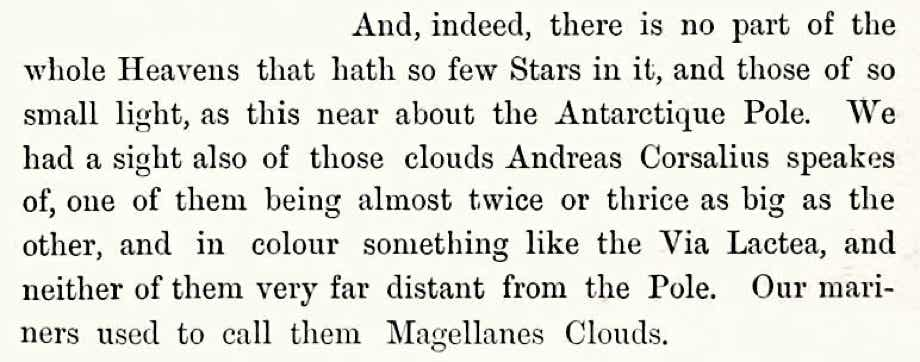

First recorded use of Magellan’s name in connection with these objects seems to be due to the English geographer and explorer Robert Hues who voyaged into the southern seas in 1586–8 and 1591–2. In his book of 1594 called Tractatus de globis et eorum usu (Treatise on Globes and Their Use) he writes: ‘We had a sight also of those clouds Andreas Corsalius speakes of, one of them being almost twice or thrice as big as the other, and in colour something like the Via Lactea [Milky Way]. Our mariners used to call them Magellanes Clouds’, indicating that the name was by then already well-established among seamen. This is confirmed by no less an authority than Edmond Halley who, in a note at the end of his Catalogus Stellarum Australium of 1679, referred to ‘two clouds, which sailors call Nebulae Magellanicae’.

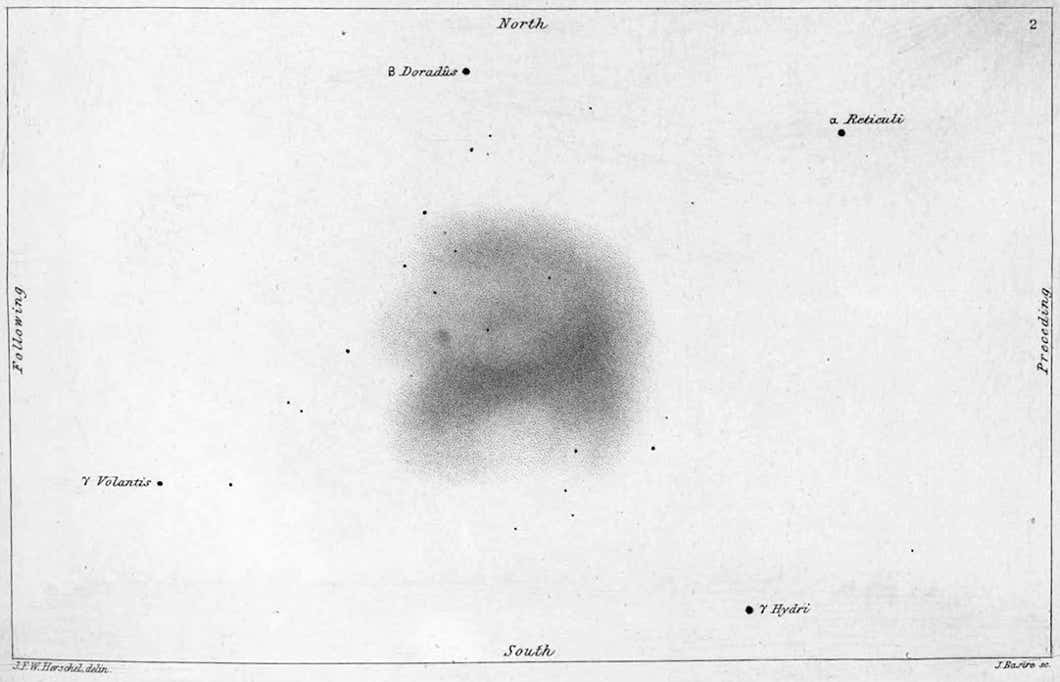

In the introduction to a catalogue of southern nebulae published in 1761 the French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille said they were commonly called ‘les nuées de Magellan’ (i.e. the clouds of Magellan). However, the modern name does not seem to have become established among astronomers until John Herschel published two drawings which he captioned ‘The two Magellanic Clouds as seen with the naked Eye’ in 1847 in his Results of Astronomical Observations made … at the Cape of Good Hope. His drawing of the large cloud is reproduced below.

Naked-eye drawing of the Large Magellanic Cloud made by John Herschel,

from his ‘Results of Astronomical Observations made … at the Cape of Good Hope’ published in 1847.

Incidentally, R. H. Allen, in his book Star Names, Their Lore and Meaning, credits the 10th-century Arab astronomer al-Ṣūfī with prior knowledge of the Large Magellanic Cloud, but this is a misunderstanding of a reference to some stars in Carina and Vela. In reality, the Arabs did not learn of the Magellanic Clouds until the end of the 15th century from the master navigator Ahmad ibn Mājid (c.1430–c.1500) only shortly before they became known in the west.

Within the Large Magellanic Cloud lies the huge nebula NGC 2070, popularly called the Tarantula, which is bright enough to have been shown as a star on Johann Bayer’s southern star chart of 1603. It is also known as 30 Doradus or the 30 Doradus Nebula; this is its number in Bode’s catalogue called Allgemeine Beschreibung und Nachweisung der Gestirne, published in 1801 to accompany his Uranographia star atlas.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

Amerigo Vespucci’s description of three ‘canopi’ in the southern sky, apparently the Magellanic Clouds and the Coalsack Nebula. This report comes from a letter Vespucci wrote to Lorenzo Pietro Francesco di Medici after his voyage to South America in 1501–02. With hindsight, the Magellanic Clouds would have been better named the Vespuccian Clouds.

Antonio Pigafetta’s description of the Magellanic Clouds, seen during Ferdinand Magellan’s first circumnavigation of the globe in 1519–22.

Robert Hues’s description of the Magellanic Clouds in his book Tractatus de globis et eorum usu (1594).

i.e. the Italian explorer Andrea Corsali (1487–15??) whose sketch and description of the area around the south celestial pole was the first accurate depiction of the Magellanic Clouds and southern cross.

Edmond Halley referred (in Latin) to ‘two clouds, which sailors call Nebulae Magellanicae’ in a note at the end of his southern star catalogue, Catalogus Stellarum Australium, which he compiled from St Helena.

Nicolas Louis de Lacaille referred to ‘les nuées de Magellan’ (the clouds of Magellan) looking like detached parts of the Milky Way in a paper on ‘nebulous stars’ in the Histoire de l'Académie royale des sciences for 1755 (but actually published in 1761). He also noted that Dutch and Danish explorers termed them the ‘cape Clouds’.