Genitive: Draconis

Abbreviation: Dra

Size ranking: 8th

Origin: One of the 48 Greek constellations listed by Ptolemy in the Almagest

Greek name: Δράκων (Drakon)

Coiled around the sky’s north pole is the celestial dragon, Draco, known to the Greeks as Δράκων (i.e. Drakon). Legend has it that this is the dragon slain by Heracles during one of his labours, and in the sky the dragon is depicted with one foot of Heracles (in the form of the neighbouring constellation Hercules) planted firmly upon its head. This dragon, named Ladon, guarded the precious tree on which grew the golden apples.

Hera had been given the golden apple tree as a wedding present when she married Zeus. She was so delighted with it that she planted it in her garden on the slopes of Mount Atlas and set the Hesperides, daughters of Atlas, to guard it. Most authorities say there were three Hesperides, but Apollodorus names four. They proved untrustworthy guards, for they kept picking the apples. Sterner measures were required, so Hera placed the dragon Ladon around the tree to ward off pilferers.

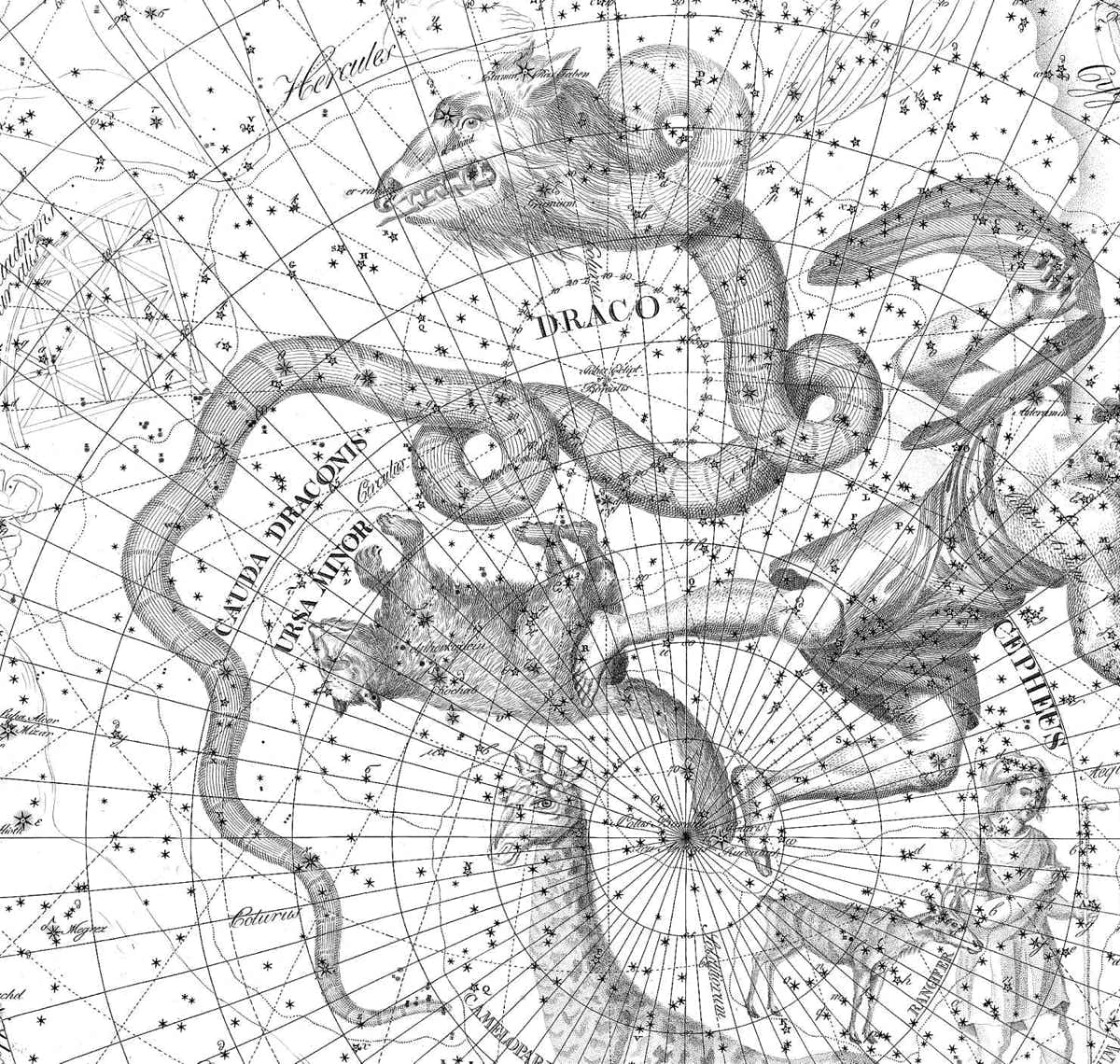

Draco winds around the north celestial pole on Chart III of Johann Bode’s Uranographia star atlas (1801). The dragon’s long tail, here labelled Cauda Draconis, extends between the two bears. At the top of the chart, the left foot of Hercules rests on the dragon’s head.

According to Apollodorus, Ladon was the offspring of the monster Typhon and Echidna, a creature half woman and half serpent. Ladon had one hundred heads, says Apollodorus, and could talk in different voices. Hesiod, though, says that the dragon was the offspring of the sea deities Phorcys and Ceto, and he does not mention the number of heads. In the sky, the dragon is single-headed.

The great hero Heracles was required to steal some apples from the tree as one of his labours. He did so by killing the dragon with his poisoned arrows. Apollonius Rhodius recounts that the Argonauts came across the body of Ladon the day after Heracles had shot him. The dragon lay by the trunk of the apple tree, its tail still twitching but the rest of its coiled body bereft of life. Flies died in the poison of its festering wounds while nearby the Hesperides bewailed the dragon’s death, covering their golden heads with their white arms. Hera placed the image of the dragon in the sky as the constellation Draco.

Stars of Draco

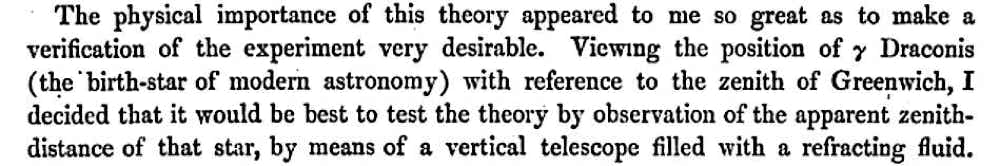

Despite its considerable size, the eighth-largest constellation by area, Draco is not particularly prominent. Its brightest star is second-magnitude Gamma Draconis, called Eltanin from the Arabic al-tinnīn meaning ‘the serpent’; according to Ptolemy it lay on the top of the dragon’s head (see illustration below). Gamma Draconis was given the accolade of ‘the birth-star of modern astronomy’ by the English Astronomer Royal Sir George Airy (1801–92) because it was the subject of the observations by James Bradley (1692–1762) that led to the discovery of the aberration of light, announced in 1728. This was the first observational proof that the Earth orbits the Sun.

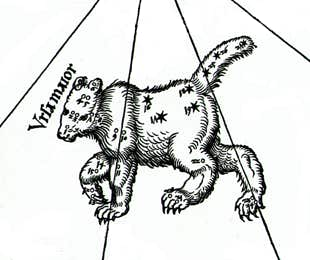

Head of Draco on Johann Bayer’s Uranometria of 1603. Gamma Draconis is on the top of its head, Beta lies next to the dragon’s eye, Xi is on its jaw, and Nu lies in its mouth, while Mu marks the tip of the tongue, all positioned as described by Ptolemy in the Almagest.

The star that Johann Bayer labelled Alpha Draconis, lying in the dragon’s body between the tail of Ursa Major and the head of Ursa Minor, is only of magnitude 3.7, but it has the distinction that it was the north pole star around 2800 BC when it lay only 0.1° from the celestial pole, closer than our modern Polaris. Alpha Draconis is named Thuban, from a highly corrupted form of the Arabic ra’s al-tinnīn, ‘the serpent’s head’, at some stage wrongly applied to this star, even though it lies nowhere near the head. Why did Bayer designate this star as Alpha? For some reason Tycho catalogued it as 2nd magnitude, making it the brightest in the constellation, and Bayer followed suit without checking for himself. Ptolemy had listed it as third magnitude, but even that was a step too bright.

Beta Draconis, near the dragon’s eye, is called Rastaban, another corrupted form of the Arabic name ra’s al-tinnīn. The stars Beta, Gamma, Nu, and Xi Draconis form a lozenge shape which we regard as the dragon’s head (see illustration above), but which bedouin Arabs visualized as four mother camels, al-‘awā’idh, with a baby camel at the centre; the baby was represented by a 6th-magnitude star not mentioned by Ptolemy which the Arabs called al-ruba’, now written as Alruba. Mu Draconis, a 5th-magnitude double star which Ptolemy described as lying on the dragon’s tongue, is known as Alrakis which comes from the Arabic al-rāqiṣ, the trotting camel.

South of the stars Theta and Iota Draconis lay the now-obsolete constellation Quadrans Muralis, introduced by Lalande in 1795, from which the Quadrantid meteor shower takes its name. On Bode’s chart Iota Draconis is given the name ed-dsich, corrupted from the Arabic al-dhīkh, referring to a male hyena. Its modern name is Edasich.

Chinese associations

Chinese astronomers imagined two walls enclosing the north polar region of the sky, and Draco contains large parts of each. (For more about this circumpolar region, see Ursa Minor.) The eastern wall started at Iota Draconis and continued via Theta, Eta, Zeta, and one or two other uncertain stars into Cepheus. The western wall ran from Alpha via Kappa and Lambda Draconis into Ursa Major and then Camelopardalis.

In far northern Draco, closest to the celestial pole, was Tianzu, ‘celestial pillars’, consisting of five faint stars, identities uncertain. These pillars were supposedly used as noticeboards for posting government orders, although they might also represent pillars supporting the sky. Just south of it was Nüyu (also given as Yunu), four stars representing the Emperor’s concubines; the stars concerned are uncertain. Next to this were Nüshi (Psi Draconis), a woman in charge of water clocks in the royal palace, and Zhuxiashi (also known as Zhushi), possibly Phi or Chi Draconis, an official recorder or scribe to the Emperor. Farther along the eastern wall of the Central Palace five stars (possibly Omega, 27, 19, 18, and 15 Draconis) formed Shangsu, the Emperor’s secretaries. Six faint stars on the borders of Draco and southern Ursa Minor formed the Emperor’s bedroom, Tianchuang.

Just outside the western wall of the Central Palace, north of the Plough, 7 and 8 Draconis formed Neichu, a private kitchen for the Emperor and his family. A second kitchen, Tianchu, lay just outside the eastern wall, consisting of Delta, Sigma, Epsilon, Rho, 64, and Pi Draconis. This kitchen catered for government officers and the Emperor’s guests.

Farther south lay Fukuang, formed by 39, 45, 46, Omicron, 48, 49, and 51 Draconis. This represented a basket containing mulberry leaves to feed silkworms. On the southern border with Hercules was Tianpei, also known as Tianbang. This represented either the Emperor’s advance guard or a flail for threshing grain, in another example of how a Chinese constellation could have widely differing meanings. It consisted of the four stars we know as the head of Draco (Beta, Gamma, Nu, and Xi Draconis) plus Iota Herculis.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

Sir George Airy, the Astronomer Royal, described Gamma Draconis as ‘the birth-star of modern astronomy’ in the Greenwich Observations of 1873. Gamma Draconis passes almost exactly overhead as seen from London and hence the effects of atmospheric refraction on its position are negligible.

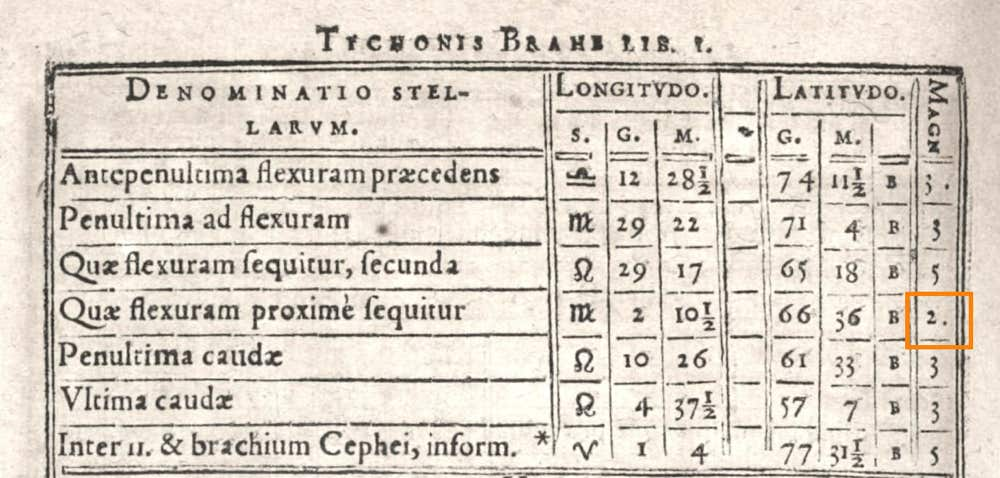

Tycho’s star catalogue listed the brightness of the star we now know as Alpha Draconis as just under magnitude 2 (in the orange box – the dot after the figure means ‘less than’). Its actual magnitude is 3.7. This scan comes from Tycho’s Astronomiae instauratae progymnasmata published in 1602, a year after his death. An edited version of Tycho’s catalogue published in 1627 as part of the Rudolphine Tables also listed this star as magnitude 2, but without the dot.