Genitive: Eridani

Abbreviation: Eri

Size ranking: 6th

Origin: One of the 48 Greek constellations listed by Ptolemy in the Almagest

Greek name: Ποταμός (Potamos)

Aratus applied the mythical name Ἠριδανός (Eridanos) to this constellation although many other authorities, including Ptolemy in the Almagest, simply called it Ποταμός (Potamos), meaning river. Eratosthenes had another identification: he said that the constellation represented the Nile, ‘the only river which runs from south to north’. Hyginus agreed, claiming that the star Canopus lay at the end of the celestial river, in the same way that the island Canopus lies at the mouth of the Nile. However, in this he was wrong, for Canopus marks a steering oar of the ship Argo and is not part of the river. Hyginus had evidently misunderstood a comment by Eratosthenes, who had simply said that Canopus lay ‘beneath’ the river, meaning that it was at a more southerly declination.

Both Eratosthenes and Hyginus overlooked the fact that the celestial river is visualized as flowing from north to south, opposite to the direction of the real Nile. Adding to the confusion, later Greek and Latin writers identified the Eridanus with the river Po which flows from west to east across northern Italy.

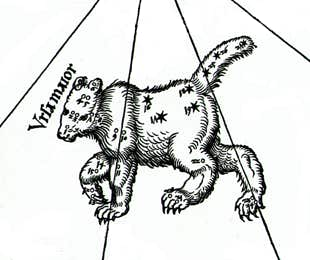

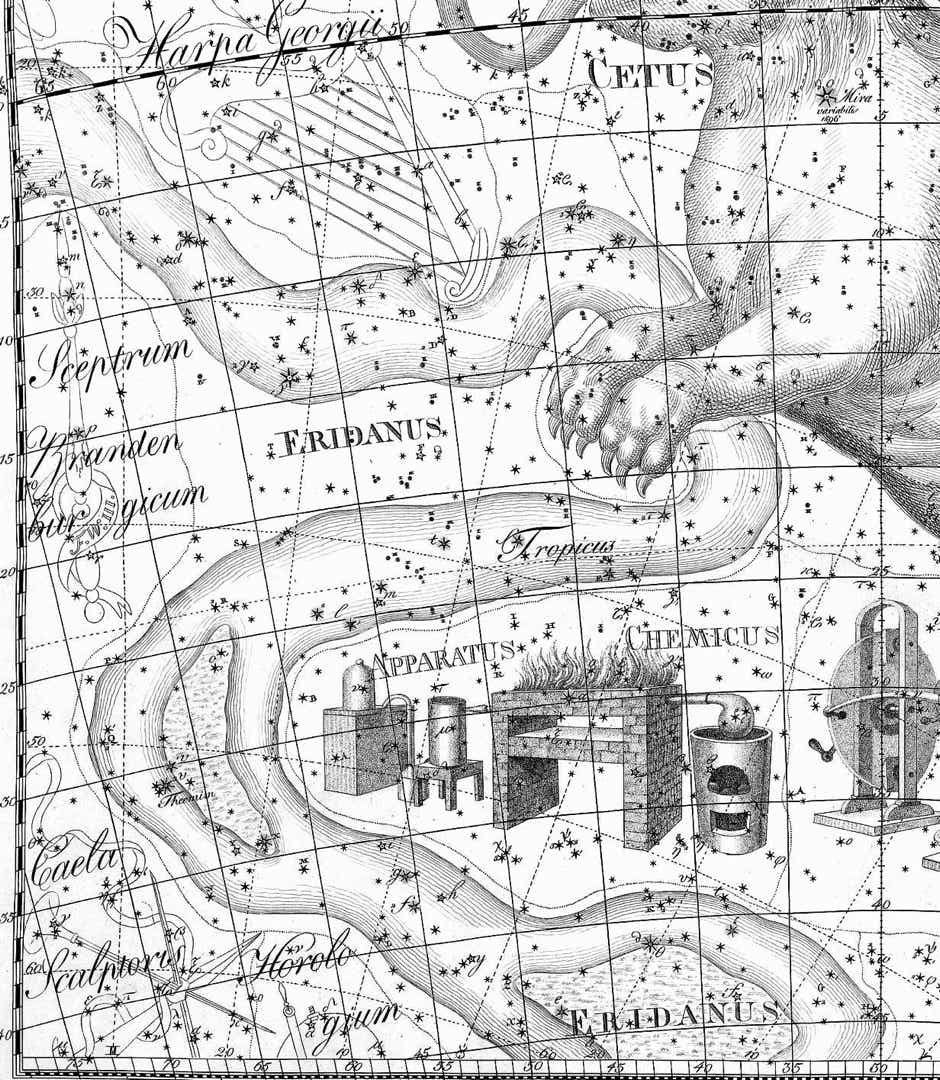

Eridanus meanders from north to south down Chart XVII in Johann Bode’s Uranographia (1801). At upper right are the flippers of Cetus, and below them lies Apparatus Chemicus, the name given by Bode to the constellation we now know as Fornax. Johann Bayer drew the river with reeds and rocks lining its banks.

In mythology, the river Eridanus features in the story of Phaethon, son of the Sun-god Helios, who begged to be allowed to drive his father’s chariot across the sky. Reluctantly Helios agreed to the request, but warned Phaethon of the dangers he was facing. ‘Follow the track across the heavens where you will see my wheel marks’, Helios advised.

As Dawn threw open her doors in the east, Phaethon enthusiastically mounted the Sun-god’s golden chariot studded with glittering jewels, little knowing what he was letting himself in for. The four horses immediately sensed the lightness of the chariot with its different driver and they bolted upwards into the sky, off the beaten track, with the chariot bobbing around like a poorly ballasted ship behind them. Even had Phaethon known where the true path lay, he lacked the skill and the strength to control the reins.

Riding for a fall

The team galloped northwards, so that for the first time the stars of the Plough grew hot and Draco, the dragon, which until then had been sluggish with the cold, sweltered in the heat and snarled furiously. Looking down on Earth from the dizzying heights, the panic-stricken Phaethon grew pale and his knees trembled in fear. Finally, he saw the menacing sight of the Scorpion with its huge claws outstretched and its poisonous tail raised to strike. The swooning Phaethon let the reins slip from his grasp and the horses galloped out of control.

Ovid graphically describes Phaethon’s crazy ride in Book II of his Metamorphoses. The chariot plunged so low that the Earth caught fire. Enveloped in hot smoke, Phaethon was swept along by the horses, not knowing where he was. It was then, the mythologists say, that Libya became a desert, the Ethiopians acquired their dark skins and the seas dried up.

To bring the catastrophic events to an end, Zeus struck Phaethon down with a thunderbolt. With his hair streaming fire, the youth plunged like a shooting star into the Eridanus. Some time later, when the Argonauts sailed up the river, they found his body still smouldering, sending up clouds of foul-smelling steam in which birds choked and died. Aratus referred to the ‘poor remains’ of Eridanus, implying that much of the river’s flow was evaporated by the heat of Phaethon’s fall.

Eridanus in the sky

Eridanus is a long constellation, the sixth-largest in the sky, meandering from the foot of Orion far into the southern hemisphere, ending near Tucana, the toucan. The present-day Eridanus has the greatest north-to-south span of any constellation, nearly 60°. Its brightest star, first-magnitude Alpha Eridani, is called Achernar, from the Arabic ākhir al-nahr meaning ‘the river’s end’; at declination –57°.2, it does indeed mark the southern end of Eridanus.

In Ptolemy’s day, though, the river dried up 17° farther north, at the star to which Johann Bayer assigned the Greek letter Theta (θ). The name Achernar was transferred from this star to its present position when Eridanus was extended south in the late 16th century. Theta Eridani was then renamed Acamar, a name that comes from the same Arabic original as Achernar. The present-day Achernar is the only first-magnitude star not listed in Ptolemy’s Almagest, because it was too far south for him to see.

Bayer, incidentally, applied the Greek letter tau (τ) to a cascade of nine stars in the middle of the river; these stars are now distinguished by superscripts from τ1 to τ9. Bayer also applied the letter upsilon (υ) to a chain of seven stars further along the river, but the letter is now applied to only four of these, υ1 to υ4.

According to the Arab star name expert Paul Kunitzsch, Bedouin Arabs visualized present-day Achernar and Fomalhaut (in Piscis Austrinus) as a pair of ostriches, al-ẓalīmān. The area around Zeta and Eta Eridani was imagined to be the ostrich’s nest, with other faint stars nearby representing ostrich eggs and chicks.

Eridanus’s southern extension

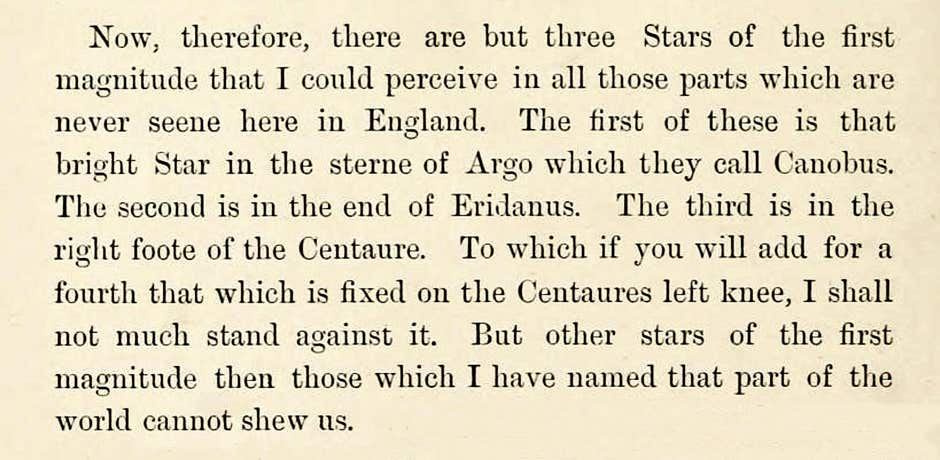

Eridanus was first shown flowing southwards to the present-day Alpha Eridani on a globe of 1598 compiled by Petrus Plancius. Plancius got his information on the southern stars from observations made by the navigator Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser during the first Dutch voyage to the East Indies (the ‘Eerste Schipvaart’) in 1595–97. Whether the idea of extending Eridanus was due to Plancius, Keyser, or some earlier navigators who had previously seen this star is not known. Perhaps Plancius was influenced by the English geographer and explorer Robert Hues (1553–1632) who studied the southern sky during two voyages in 1586–8 and 1591–2. In his book of 1594 called Tractatus de globis et eorum usu (Treatise on Globes and Their Use) Hues wrote of seeing three first-magnitude southern stars that are never visible from England, one of them ‘in the end of Eridanus’; this can only have been the present-day Achernar.

The southern extension of the river to Achernar consisted of five stars in all, as seen on the chart of Eridanus in Bayer’s Uranometria of 1603. Bayer included these five new stars in the catalogue that accompanied the chart, labelling them in order of increasing southerly declination with the Greek letters Iota (ι), Kappa (κ), Phi (φ), Chi (χ), and Alpha (α), which they still bear today. These same five stars can also be seen in the lower left of Bayer’s chart of the twelve new southern constellations invented by the Dutch navigators.

Chinese associations

In the Chinese sky, much of modern Eridanus was taken up by two constellations whose names both transliterate as Tianyuan. The more northerly of the two consisted of a large arc of 16 stars from Gamma Eridani via Delta and Eta to Tau-9, the same as the large meander in northern Eridanus that we visualize today; in China, this group was the celestial fields where animals were sacrificed to the gods, or alternatively where animals were reared for hunting. The second Tianyuan consisted of a chain of 13 stars starting at Upsilon-1 Eridani and heading south via Theta towards Kappa and possibly beyond, much as southern Eridanus is visualized today; this stretch represented the celestial orchard full of fruit trees, possibly the orchard of Xi Wang Mu, the Chinese goddess of immortality (although the Dunhuang manuscript described it as Tianpu, a vegetable garden).

Running from north to south along the present-day borders with Orion and Lepus was a chain of nine stars called Jiuliu or Jiuyou, nine flags or banners of the Emperor that formed part of the hunting scene visualized in this area (for more, see under Orion). Next to Jiuliu in northern Eridanus was a loop of nine stars forming Jiuzhou shukou, representing interpreters for visitors to the hunt from far-off regions.

Beta, Psi, and Lambda Eridani were joined with Tau Orionis to make a square next to Rigel called Yujing, the jade well for exclusive use by the nobility; the well for ordinary soldiers, Junjing, was to the south in Lepus.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

Robert Hues’s description of three first-magnitude stars that he saw in the southern sky, from his book of 1594 called Tractatus de globis et eorum usu. The one ‘in the end of Eridanus’, as he described it, is the modern Achernar. The third and fourth stars he mentions are Alpha and Beta Centauri. His note that there were no other first-magnitude stars was a riposte to Amerigo Vespucci’s absurd claim made earlier in the century that he had seen about 20 stars in the southern hemisphere as bright as Venus or Jupiter. Hues circumnavigated the globe in 1586–8 with the English explorer Sir Thomas Cavendish, and also took part in a second attempted circumnavigation with Cavendish in 1591–2 which was beaten back by bad weather around the southern tip of South America.