Flamsteed numbers —

where they really came from

FLAMSTEED NUMBERS are the numerals attached to stars in a constellation for identification purposes, such as 61 Cygni or 51 Pegasi. They are named after the English Astronomer Royal John Flamsteed (1646–1719), who produced the first major star catalogue made with the aid of a telescope, Catalogus Britannicus, published posthumously in 1725. It is often assumed that the so-called Flamsteed numbers were assigned to the stars by Flamsteed himself, but that is not the case. Flamsteed’s published catalogue contained no such numbering system. So where did they come from?

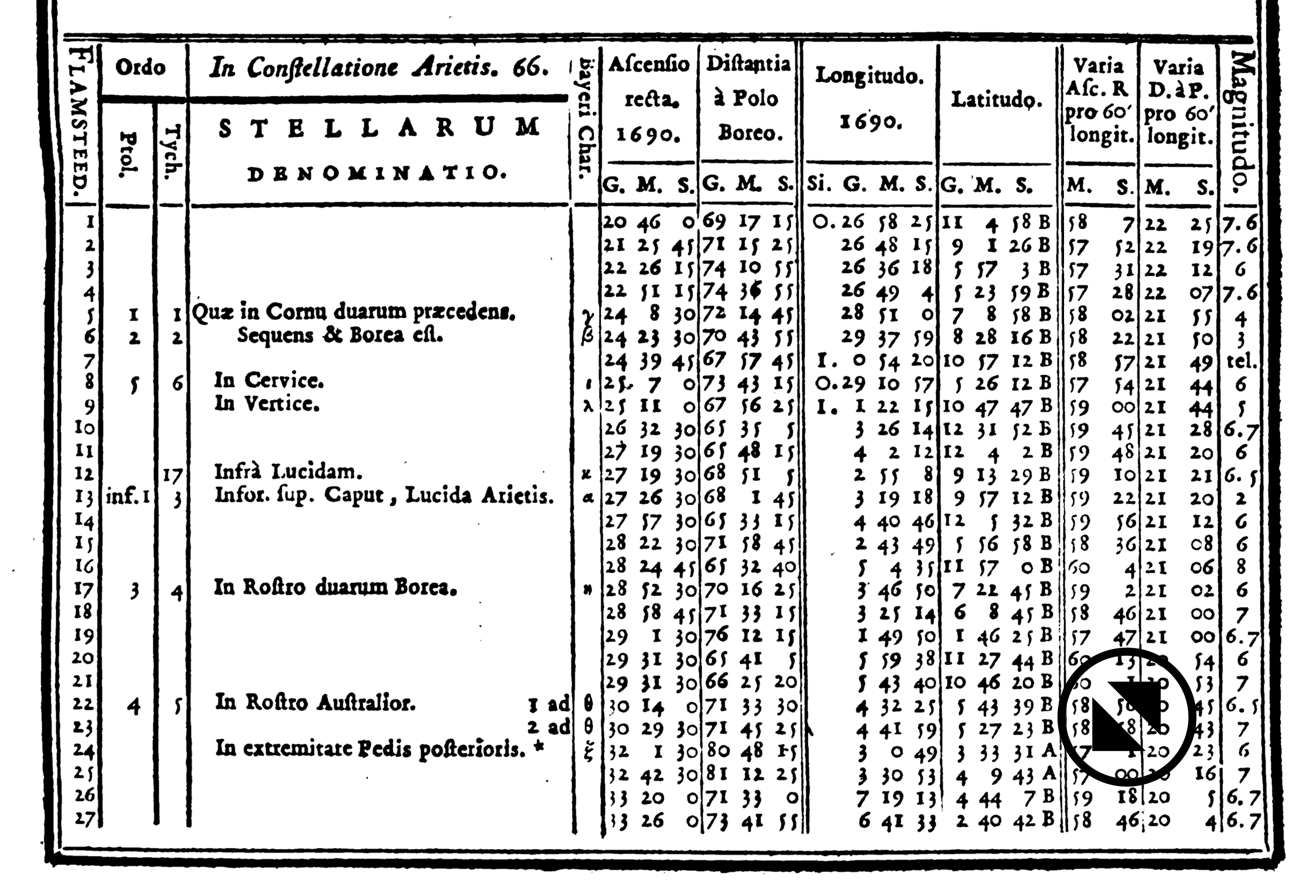

The American science historian Deborah Jean Warner seems to have been the first to point out that the numbers we now use were actually allocated by a French astronomer, Joseph Jérôme de Lalande (1732–1807). They appeared in a revised edition of Flamsteed’s catalogue published in 1783 in a French almanac, Éphémérides des mouvemens célestes. In this French edition, Lalande numbered Flamsteed’s stars consecutively by constellation. This is the numbering system we now know as ‘Flamsteed numbers’. The illustration below shows an example from the first page of Lalande’s edition.

Lalande’s revised edition of Flamsteed’s catalogue

Above: The first page of J. J. Lalande’s edited and corrected version of John Flamsteed’s star catalogue, published in 1783. The stars shown on this page belong to the constellation Aries. In the first column, Lalande numbered each star consecutively by constellation. These are the numbers that we now call Flamsteed numbers. There was no such column in Flamsteed’s original catalogue. Click on the illustration for an enlargement of the page, or click here to see the whole of Lalande’s edited catalogue.

Lalande noted in his Introduction that he got the idea from the unofficial 1712 edition of Flamsteed’s catalogue: ‘J’ai ajouté au Catalogue les nombres 1, 2, 3, &c. qui expriment l’ordre & le nombre des Etoiles de chaque constellation, & qui étoient dans l’édition de 1712, mais avec un arrangement différent’ (‘I added to the Catalogue the numbers 1, 2, 3, &c. which express the order and number of the stars of each constellation, and which were in the 1712 edition, but with a different arrangement’).

There is a complicated story behind the unofficial edition of 1712, which was produced by Edmond Halley from Flamsteed’s preliminary data at the prompting of Isaac Newton, much to Flamsteed’s fury. In this unauthorized version, numbers were added to the stars, but they are not in the same order as the Flamsteed numbers we know today: Flamsteed’s final catalogue contained more stars than the bootleg one, and he moved some stars between constellations, thereby changing the sequence. To add to the insult, the London mapmaker John Senex (1678–1740) produced a set of charts of the zodiac in 1718, based on the pirated catalogue, followed a few years later by charts of the northern and southern celestial hemispheres, the latter including Halley's observations of the southern stars made from St Helena over 40 years earlier.

Although there were no Flamsteed numbers in Flamsteed’s own catalogue, he did include columns noting the order of appearance of each star in the catalogues of Ptolemy (the Almagest) and Tycho Brahe, plus a third column with the Greek letters assigned by Johann Bayer (the so-called Bayer letters). These columns were repeated by Lalande in his French edition. In the example above, the abbreviation ‘inf’ in the Ptolemy column refers to the so-called informatae, or unformed, stars that Ptolemy regarded as lying outside the constellation figure proper. The star referred to here is the one we know as Alpha Arietis, the brightest star in the modern Aries. Despite its brightness, Ptolemy decided it did not fit the constellation figure. Instead, he placed it among the informatae.

The German astronomy historian Wolfgang Steinicke has pointed out that Johann Bode anticipated Lalande by several years. Bode introduced a column headed ‘Fl. No.’ in a star catalogue published in 1776 as part of a set of tables called Sammlung astronomischer Tafeln. However, Bode’s catalogue was not simply a copy of Flamsteed’s: it contained more entries, and he even assigned ‘Flamsteed numbers’ to stars not listed by Flamsteed. A comparison of these two catalogues with a modern listing such as the Bright Star Catalogue makes it clear that it was Lalande’s numbering that was adopted by later astronomers, not Bode’s.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved