Genitive: Chamaeleontis

Abbreviation: Cha

Size ranking: 79th

Origin: The 12 southern constellations of Keyser and de Houtman

The celestial chameleon, named after the colour-changing lizard, is one of the constellations representing exotic animals introduced by the Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman when they charted the southern skies in 1595–97. These new southern constellations were first shown on a globe by their fellow Dutchman Petrus Plancius in 1598 and were rapidly adopted by other map makers such as Johann Bayer, since no other observations of the far southern skies were then available. Chamaeleon lies near the south celestial pole, in close pursuit of Musca, the fly.

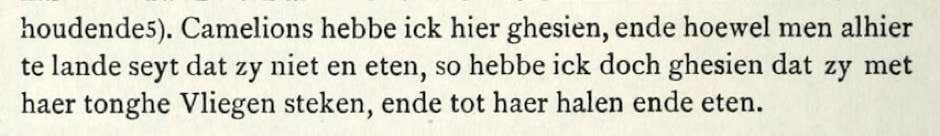

Chameleons are particularly common in Madagascar, where the Dutch fleet stopped to rest and resupply in 1595 on its way to the East Indies, so the seafarers would have seen plenty of them there. In his account of the voyage, titled De eerste schipvaart der Nederlanders naar Oost-Indië, the explorer Willem Lodewyckz wrote ‘I saw that they flick their tongues at flies which they thus catch and eat’ (thanks to Rob van Gent for the translation). However, on Plancius’s globe of 1598 the fly lies above the chameleon’s head and is unnamed, which suggests that the globe makers did not at first understand the relationship between the two new figures.

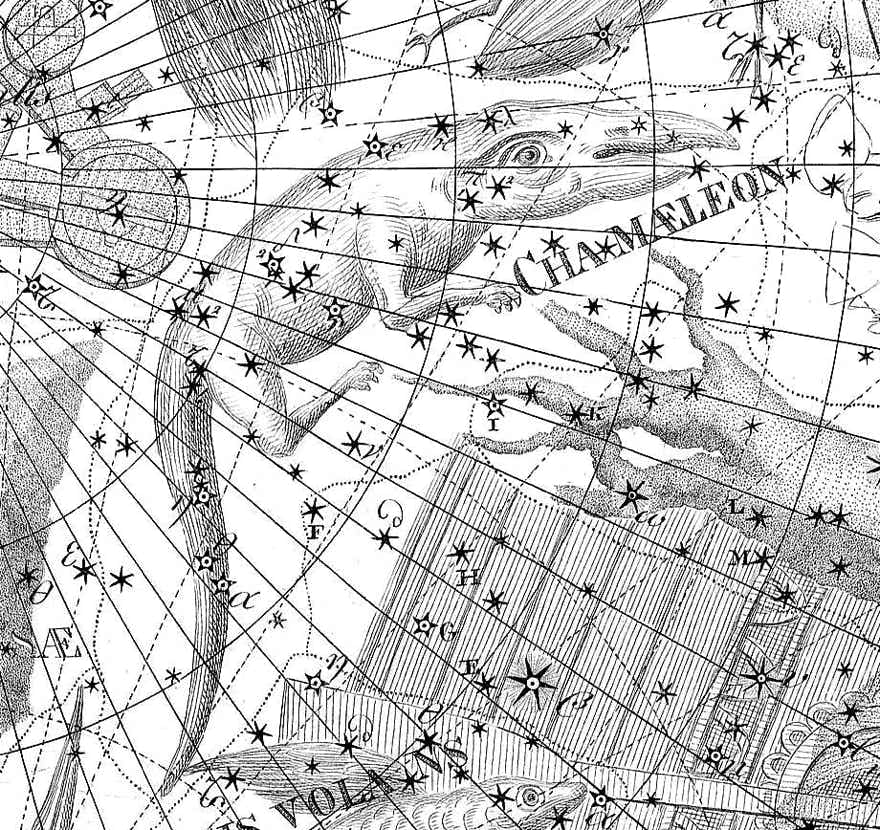

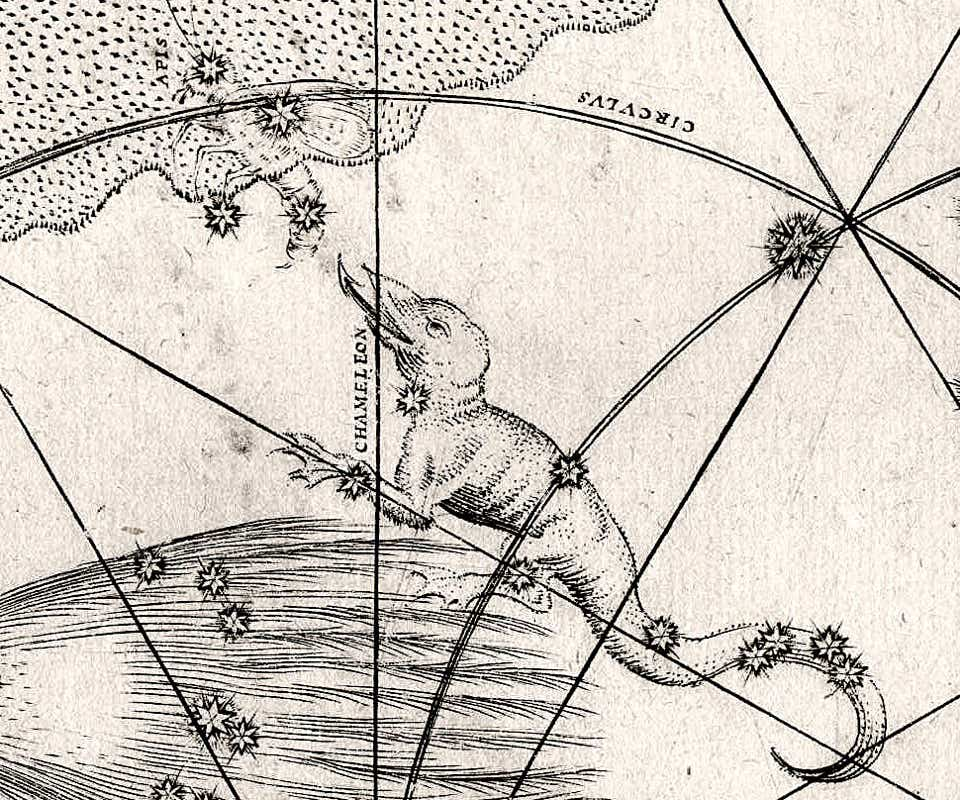

Chamaeleon as depicted on Chart XX of the Uranographia of Johann Bode (1801).

Unlike in some other representations it is ignoring the fly, Musca, which lies above its head, off the top of this illustration.

On a globe of 1600, the Dutch cartographer Jodocus Hondius (1563–1612) rearranged the pair to depict the chameleon sticking out its tongue to catch the fly, as Lodewyckz had described. However, Hondius did not name the fly, perhaps considering the two figures as a joint constellation. Three years later, Johann Bayer in his Uranometria showed the chameleon in the same pose yet evidently failed to appreciate what the adjacent insect, then still unnamed, was supposed to be – he depicted it not as a fly but a bee and named it Apis, as did Bode nearly 200 years later. Its modern name is Musca.

Plancius, Hondius, and Bayer oriented the chameleon with its feet towards the south celestial pole, but Edmond Halley turned it round so that it had its back to the pole on his southern star chart of 1678, and that is how it has been depicted ever since.

Chamaeleon has no legends associated with it, and its brightest stars are only of fourth magnitude.

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

Willem Lodewyckz’s description of chameleons from his book De eerste schipvaart der Nederlanders naar Oost-Indië (1598). He wrote: ‘Camelions hebbe ick hier ghesien, ende hoewel men alhier te lande seyt dat zy niet en eten, so hebbe ick doch ghesien dat zy met haer tonghe Vliegen steken, ende tot haer halen ende eten,’ or in English, ‘I saw chameleons here [Madagascar] and although the locals claim that they never eat anything, I saw that they flick their tongues at flies which they thus catch and eat.’ Thanks to Rob van Gent for the translation.

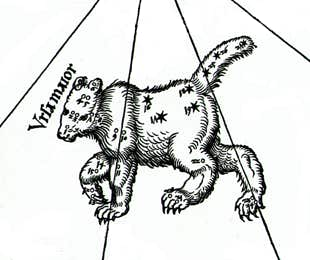

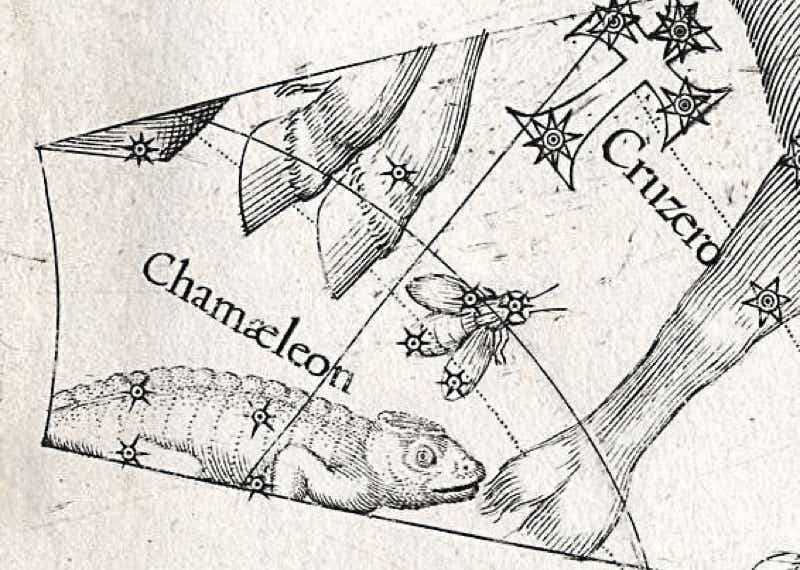

The chameleon and the fly depicted on a gore from Plancius’s celestial globe of 1598. The fly was unnamed, and remained so until Johann Bayer mistakenly dubbed it Apis, the bee, on his Uranometria atlas of 1603. Cruzero, at upper right, is the Southern Cross, under the body of Centaurus. (Nicolai Collection of the State Library of Württemberg, Stuttgart)