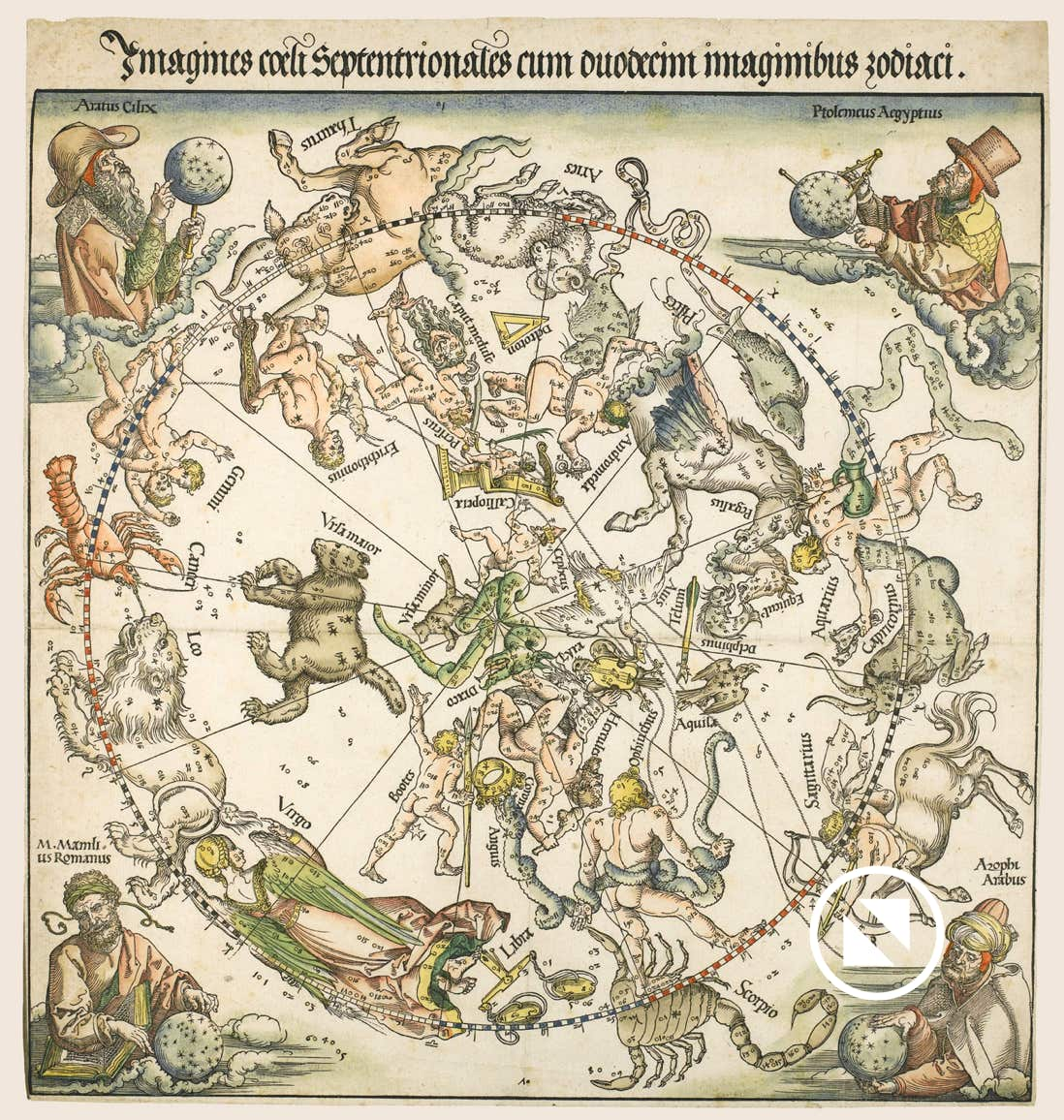

Dürer’s hemispheres of 1515 —

the first European printed star charts

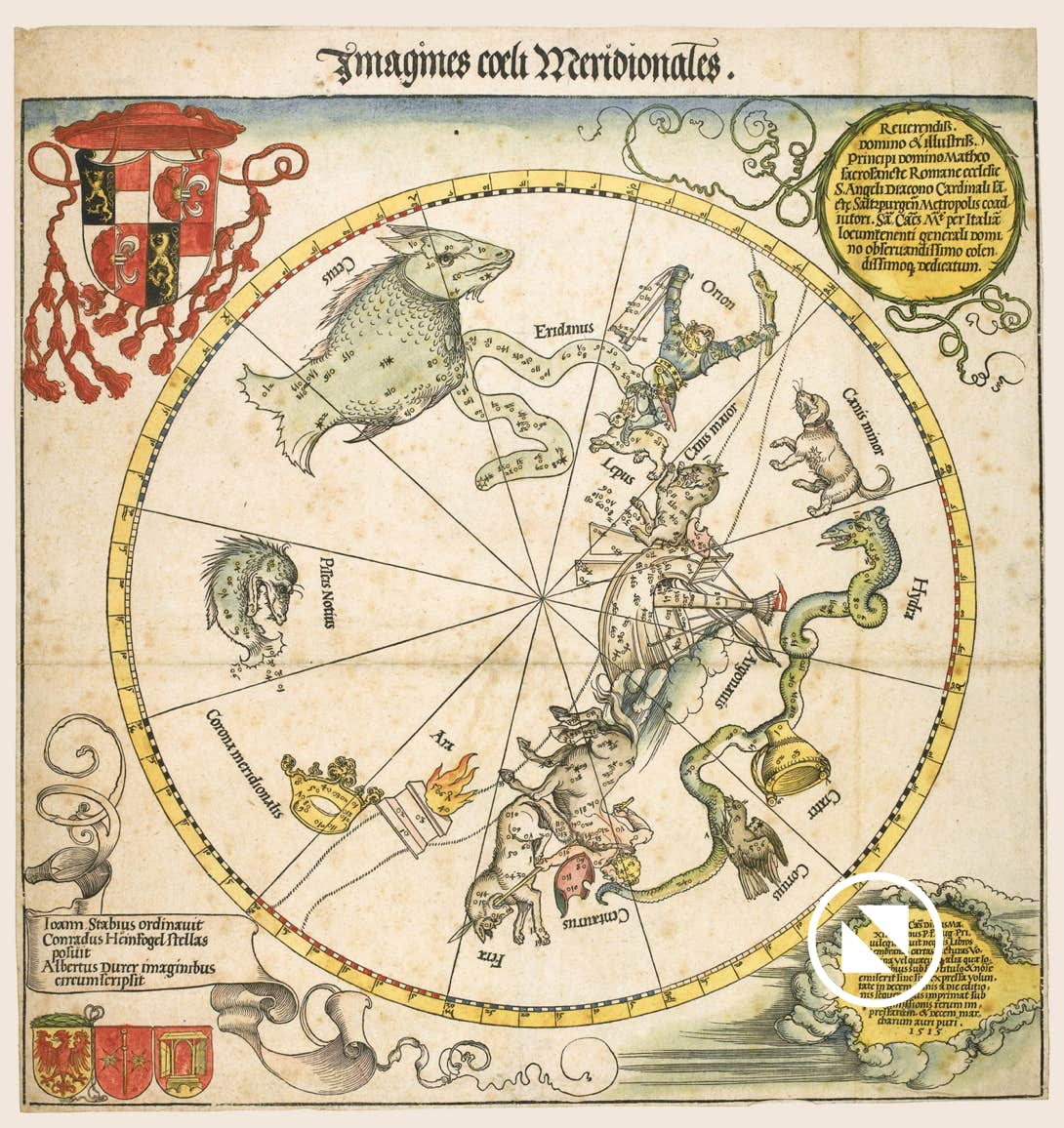

Constellations of the northern and southern skies, engraved by Albrecht Dürer and published in 1515 in Nuremberg, Germany. The pair illustrated here is one of only three examples known with contemporary hand colouring. These particular charts sold at auction at Sotheby’s in March 2011 for £361,250 ($578,542).

SHOWN here is the oldest printed star chart from Europe, published in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1515. (It is not the oldest printed star chart in the world, though – credit for the first printed star charts of all goes back over four hundred years earlier to China, where woodcut charts were made around 1090 by the Chinese astronomer Su Song and published in his book Xin yixiang fayao.) Prior to 1515, all European and Arab star charts were individually hand-drawn, and hence restricted to single copies. With the advent of printing, large numbers of identical copies could be produced at will.

The chart consists of a pair of woodcuts 43 cm (17 inches) in overall width depicting the northern and southern skies as known to European astronomers at that time, with constellation figures as they were visualized by the Greeks and Romans. As well as the 48 standard Ptolemaic figures, the chart includes Caput Meduse (sic), the head of the Gorgon, held by Perseus. The constellation figures are shown reversed, as they would appear on a celestial globe, and the constellations of the zodiac progress anticlockwise.

Whereas modern charts have the celestial equator around the rim and the celestial pole at the centre, on these charts it is the zodiac that lies around the rim. As a result there are not many constellations to show in the southern half of the chart, for the far southern skies had not then been charted by Europeans.

Dürer and his collaborators

The woodcuts were engraved by the German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) who usually gets sole credit for them, although he was only one of three authors involved in their preparation. First of these, and apparently the initiator of the project, was Johannes Stabius (c.1460–1522), an Austrian mathematician and cartographer, who designed the projection of the charts. He and Dürer had just produced a map of the known world, and this was a natural next step.

Ptolemy’s star catalogue in the Almagest was the source of the stars shown. Their positions were updated to 1500 and plotted by Conrad Heinfogel (?–1517), a German astronomer. The stars are numbered according to the order in which they were listed in the Almagest, including the 108 ‘unformed’ stars that did not fit into any constellation (for what became of those see here). Stars of first and second magnitude, and some of third magnitude, are shown by star-shaped symbols, open or filled, while fainter stars are marked simply as small open circles. Radial lines at 30° intervals (corresponding to the 12 signs of the zodiac) and a scale around the rim allowed the positions of stars to be read off with accuracy. The path of the Milky Way snakes across both charts, bordered by hatched lines.

Dürer was responsible for the pictorial content, and he seems to have borrowed heavily from two pairs of manuscript charts, one pair drawn in Vienna around 1440 and the other produced in Nuremberg in 1503 by Heinfogel in collaboration with an unknown artist. Heinfogel’s 1503 maps can be regarded as a prototype of these more accurate and artistically superior 1515 woodcuts.

Ancient authorities

In the corners of the northern chart, Dürer depicted the four ancient authorities on whose descriptions the constellation figures are based. At top left is Aratus Cilix (Aratus of Soli in Cilicia, who wrote the astronomical poem called the Phaenomena); top right is Ptolemeus Aegyptus (Ptolemy, who worked at Alexandria in Egypt and published a great star catalogue in the Almagest); bottom left is M. Mamlius Romanus (Marcus Manilius, a Roman astrologer of the first century AD who wrote a book of constellation lore called Astronomica); and finally Azophi Arabus (al-Ṣūfī, the Arab astronomer who revised and updated the star catalogue in the Almagest).

In the lower left corner of the southern hemisphere chart Dürer notes the contributions of Stabius, Heinfogel, and himself above their individual coats of arms. At top left is the coat of arms of the Archbishop of Salzburg, Cardinal Matthäus Lang, and at top right is a dedication to him. Finally, there is an acknowledgement to the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I, who was the patron of Stabius and Dürer.

Derivatives

Being available in multiple copies, and combined with the artistic reputation of Dürer, these charts were highly influential. Derivatives soon appeared, most notably a planisphere produced in 1536 by another German, Peter Apian (1495–1552) (known in Latin as Petrus Apianus), and subsequently included in a book of his in 1540 called Astronomicum Caesareum. Apian’s chart is drawn in the form of an eight-sided astrolabe, complete with carrying handle. On his chart Apian introduced some Arabic-derived star names, as in this example from Ursa Major. In 1537 the Dutch cartographers Gemma Frisius and Gerardus Mercator copied Dürer’s constellation figures for a celestial globe.

All these charts suffered from a drawback: they showed the constellations back to front, as on a globe, rather than the way they actually appear in the sky, which made them awkward for observational use. The first printed star charts showing the constellation figures the right way round (i.e. a geocentric view rather than a globe view) were created by the Transylvanian cartographer Johannes Honter (1498–1549) in 1532, although not widely published until included in an edition of Ptolemy’s collected works in 1541. On Honter’s charts the male constellations were depicted in contemporary clothing, unlike the classical nudes of Dürer and Apianus.

● For an in-depth discussion of these star charts, see The Visualization of Perspective Systems and Iconology in Dürer’s Cartographic Works by Adèle Lorraine Wörz, pages 156–178 (but beware of typos).

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved