Genitive: Ursae Majoris

Abbreviation: UMa

Size ranking: 3rd

Origin: One of the 48 Greek constellations listed by Ptolemy in the Almagest

Greek name: Ἄρκτος Μεγάλη (Arktos Megale)

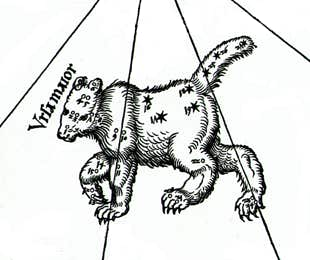

Undoubtedly the most familiar star pattern in the entire sky is the seven stars that make up the shape popularly termed the Plough or Big Dipper, part of the third-largest constellation, Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The seven stars form the rump and tail of the bear, while the rest of the animal is comprised of fainter stars. Its Greek name in the Almagest was Ἄρκτος Μεγάλη (Arktos Megale); Ursa Major is the Latin equivalent.

Aratus in the third century BC called the constellation Ἑλίκη (Helike, or Helice in Latin), meaning ‘twister’, apparently from its circling of the pole, and said that the ancient Greeks steered their ships by reference to it. In the Odyssey, for example, we read that Odysseus kept the great bear to his left as he sailed eastwards. The Phoenicians, on the other hand, used the Little Bear (Ursa Minor), which Aratus termed Κυνόσουρα (Kynosoura, or Cynosura in Latin). Aratus tells us that the bears were also called wagons or wains (ἅμαξαi in Greek) because they wheeled around the pole, and in one place he referred to the figure of Ursa Major as the ‘wagon-bear’ to underline its dual identity.

Homer in the Odyssey referred to ‘the Great Bear that men call the Wain, that circles opposite Orion, and never bathes in the sea’, the last phrase being a reference to its circumpolar (non-setting) nature. The adjacent constellation Boötes was imagined as either the herdsman of the bear or the wagon driver. Germanicus Caesar early in the first century AD seems to have been the first to mention a third, now-common identity – he said that the bears were also called ploughs because, as he wrote, ‘the shape of a plough is the closest to the real shape formed by their stars’.

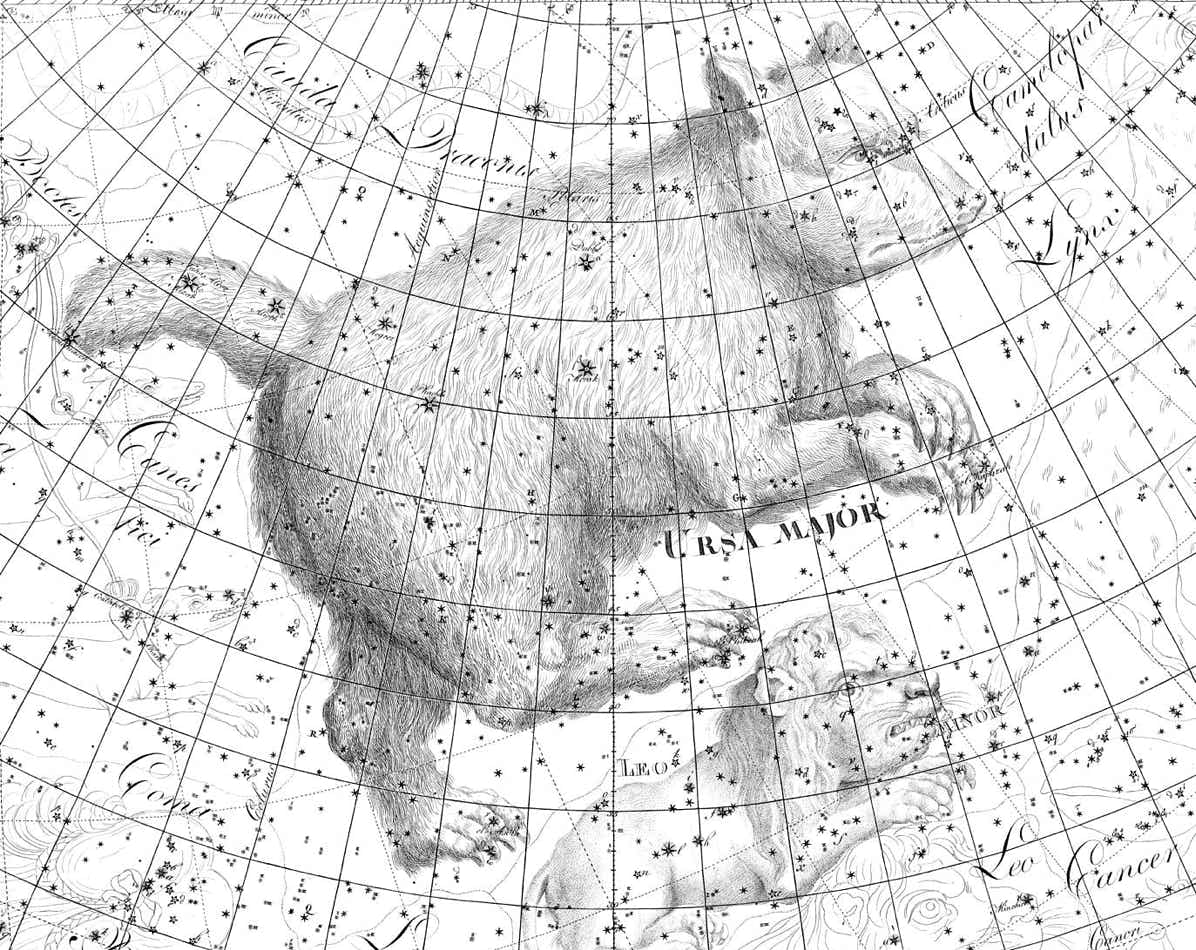

Ursa Major as depicted on Chart VI of the Uranographia of Johann Bode (1801).

The familiar shape popularly known as the Plough or Big Dipper is made up of

seven stars in the rump and tail of the bear.

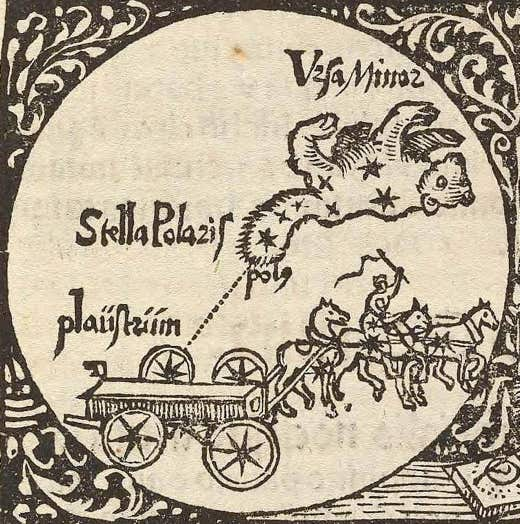

According to Hyginus the Romans referred to the Great Bear as Septentrio, meaning ‘seven plough oxen’, although he added the information that in ancient times only two of the stars were considered oxen, the other five forming a wagon. On a diagram of the north polar sky from 1524 the German astronomer Peter Apian (1495–1552), also known by the Latin name Petrus Apianus, showed Ursa Major as a team of three horses pulling a four-wheeled cart, which he called Plaustrum, harking back to the Roman tradition. The word septentrional was commonly used in Latin as a synonym for ‘north’.

In mythology, the Great Bear is identified with two separate characters: Callisto, a paramour of Zeus; and Adrasteia, one of the ash-tree nymphs who nursed the infant Zeus. To complicate matters, there are several different versions of each story, particularly the one involving Callisto.

The story of Callisto

Callisto is usually said to have been the daughter of Lycaon, king of Arcadia in the central Peloponnese. (An alternative story says that she is not Lycaon’s daughter but the daughter of Lycaon’s son Ceteus. In this version, Ceteus is identified with the constellation Hercules, kneeling and holding up his hands in supplication to the gods at his daughter’s transformation into a bear.)

Callisto joined the retinue of Artemis, goddess of hunting. She dressed in the same way as Artemis, tying her hair with a white ribbon and pinning together her tunic with a brooch, and she soon became the favourite hunting partner of Artemis, to whom she swore a vow of chastity. One afternoon, as Callisto laid down her bow and rested in a shady forest grove, Zeus caught sight of her and was entranced. What happened next is described fully by Ovid in Book II of his Metamorphoses. Cunningly assuming the appearance of Artemis, Zeus entered the grove to be greeted warmly by the unsuspecting Callisto. He lay beside her and embraced her. Before the startled girl could react, Zeus revealed his true self and, despite Callisto’s struggles, had his way with her. Zeus returned to Olympus, leaving the shame-filled Callisto scarcely able to face Artemis and the other nymphs.

On a hot afternoon some months later, the hunting party came to a cool river and decided to bathe. Artemis stripped off and led them in, but Callisto hung back. As she reluctantly undressed, her advancing pregnancy was finally revealed. She had broken her vow of chastity! Artemis, scandalized, banished Callisto from her sight.

Callisto becomes a bear

Worse was to come when Callisto gave birth to a son, Arcas. Hera, the wife of Zeus, had not been slow to realize her husband’s infidelity and was now determined to take revenge on her rival. Hurling insults, Hera grabbed Callisto by her hair and pulled her to the ground. As Callisto lay spreadeagled, dark hairs began to sprout from her arms and legs, her hands and feet turned into claws and her beautiful mouth which Zeus had kissed turned into gaping jaws that uttered growls.

For 15 years Callisto roamed the woods in the shape of a bear, but still with a human mind. Once a huntress herself, she was now pursued by hunters. One day she came face to face with her son Arcas. Callisto recognized Arcas and tried to approach him, but he backed off in fear. He would have speared the bear, not knowing it was really his mother, had not Zeus intervened by sending a whirlwind that carried them up into heaven, where Zeus transformed Callisto into the constellation Ursa Major and Arcas into Boötes.

Hera was now even more enraged to find her rival glorified among the stars, so she consulted her foster parents Tethys and Oceanus, gods of the sea, and persuaded them never to let the bear bathe in the northern waters. Hence, as seen from mid-northern latitudes, the bear never sets below the horizon.

That this is the most familiar version of the myth is due to Ovid’s pre-eminence as a storyteller, but there are other versions, some older than Ovid. Eratosthenes, for instance, says that Callisto was changed into a bear not by Hera but by Artemis as a punishment for breaking her vow of chastity. Later, Callisto the bear and her son Arcas were captured in the woods by shepherds who took them as a gift to King Lycaon. Callisto and Arcas sought refuge in the temple of Zeus, unaware that Arcadian law laid down the death penalty for trespassers. (Yet another variant says that Arcas chased the bear into the temple while hunting – see Boötes.) To save them, Zeus snatched them up and placed them in the sky.

The Greek mythographer Apollodorus says that Callisto was turned into a bear by Zeus to disguise her from his wife Hera. But Hera saw through the ruse and pointed out the bear to Artemis who shot her down, thinking that she was a wild animal. Zeus sorrowfully placed the image of the bear in the sky.

Other identifications

Aratus makes a completely different identification of Ursa Major. He says that the bear represents one of the nymphs who raised Zeus in the cave of Dicte on Crete. That cave, incidentally, is a real place where local people still proudly point out the supposed place of Zeus’s birth. Rhea, his mother, had smuggled Zeus to Crete to escape Cronus, his father. Cronus had swallowed all his previous children at birth for fear that one day they would overthrow him – as Zeus eventually did. Apollodorus names the nurses of Zeus as Adrasteia and Ida, although other sources give different names. Ida is represented by the neighbouring constellation of Ursa Minor, the Little Bear.

These nymphs looked after Zeus for a year, while armed Cretan warriors called the Curetes guarded the cave, clashing their spears against their shields to drown the baby’s cries from the ears of Cronus. Adrasteia laid the infant Zeus in a cradle of gold and made for him a golden ball that left a fiery trail like a meteor when thrown into the air. Zeus drank the milk of the she-goat Amaltheia with his foster-brother Pan. Zeus later placed Amaltheia in the sky as the star Capella, while Adrasteia became the Great Bear – although why Zeus turned her into a bear is not explained.

Why a bear?

An enduring puzzle concerning Ursa Major and its companion Ursa Minor is why they came to be regarded as bears when they do not look at all bear-like. Both of the celestial bears have long tails, which real bears do not, an anatomical oddity which the mythologists never explained. Thomas Hood, an English astronomical writer of the late 16th century, offered the tongue-in-cheek suggestion that the tails had become stretched when Zeus pulled the bears up into heaven. ‘Other reason know I none’, he added apologetically.

Peter Blomberg, a Swedish historian of astronomy, has proposed that the identification of these constellations as bears is due to a linguistic ambiguity. The early Greeks referred to the northern area of the sky as αρκτος (i.e. arktos), a word which can mean northern (as in Arctic) as well as bear. Blomberg believes that the word was originally used in the former sense, i.e. that the constellations were in the north, and that its alternative meaning, that of a bear, was adopted by the Romans in the first century AD, a century or so before Ptolemy codified the constellation figures in his Almagest. Is it possible, in that case, that two of our most familiar and best-loved constellations owe their identities to a simple misinterpretation?

CONTINUE TO URSA MAJOR PART 2 »

© Ian Ridpath. All rights reserved

Ursa Major shown as a team of three horses, the middle one with a rider, pulling a four-wheeled cart, from the Cosmographicus Liber of 1524 by the German astronomer and mathematician Peter Apian (1495–1552). Apian called it Plaustrum, the Latin name for a horse-drawn cart. The constellations are shown in reverse, as on a celestial globe. A later version has the constellations the right way round, as seen in the sky.